Klundert and Willemstad 1793

Dutch During the

Revolutionary Wars Part 9

Siege of Willemstad: Preliminaries

by Geert van Uythoven, Netherlands

| |

Besides advancing to Klundert the French Advance Guard, commanded by adjudant général Berneron, also advanced to the fortress-city Willemstad. Willemstad lies, together with the fortress-city Klundert, on the south bank of the Hollandsch Diep, on what originally had been an island. The fortress had and still has, as has Breda, the Stadtholder as its Lord.

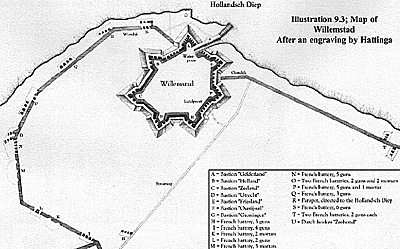

Illustration 9.3; Map of Willemstad After an engraving by Hattinga.

See the accompanying map of the fortress to illustrate the following. The city consists of nine streets with about 180 houses, and in 1793 just over seven hundred inhabitants. The citizens made their living mainly out of the presence of the garrison, and besides keeping many shops most of them were artisan or labourer. In addition some of them were farmer or fisherman. Except for the houses and shops, the city had in the centre a church with a huge dome (R), a town hall (L), a government house called ‘Prinsenhof’ (S), barracks and an arsenal (M), a powder magazine (P), and finally an orphanage. The walls of the city were a half hour walking long, and included seven bastions, named after the seven provinces of the Dutch Republic (A-G). Access to the fortress was by two gates. One gate, the ‘Waterpoort’ (K), was situated next to the harbour entrance, covered by the Hollandsch Diep. The other gate to the southeast was called ‘Landpoort’ (I), and covered by a ravelin (H). A ditch filled with water surrounds the fortress. The ditch has two dams, called ‘Westbeer’ (x) and ‘Oostbeer’ (a). These are brick walls, between the water in the ditch and the water from the Hollandsch Diep. To prevent entrance into the fortress by the Oostbeer, it had a so-called ‘monk’ on top. The fortress had no casemates or vaulted cells’ inside the walls, which could provide shelter during an enemy bombardment. Willemstad was strategically important, and was seen as the key to Holland. French possession of the fortress would prevent all Dutch shipping on the Hollandsch Diep, and would give a useful harbour from which a crossing of the river could be undertaken. Now Willemstad would become the symbol of Dutch resistance against the French invasion. [4]

Before the hostilities around the fortress-city commenced, the garrison of Willemstad consisted of the 1st battalion of the Regiment Saxen-Gotha, a German regiment serving the Dutch Republic, and twenty artillerymen, most from the 5th Company (Captain Sloet, not present) of the 1st Artillery Regiment, commanded by the Lieutenant of the artillery Simon Jacobus Colthof. Some of the artillerymen came from

the companies Willem du Pont and Count de Gimèl. Commander of the fortress was Colonel Johan Ludwig Ernst Schepern, commanding the Regiment Saxen-Gotha in the absence of the Prince of Saxen-Gotha, nominal commander of the regiment. An attack on the fortress was of course expected.

On 13 February, the magistrate received orders from The Hague to take care for sufficient provisions, for the garrison as well as the citizens, to withstand a siege for three months. The next day Colonel Schepern arrived, accompanied by Captain of the Engineers Frans Jacob Alexander Berg. On the 15th they, accompanied by the other officers present, inspected the defence works, after which plans for the defence of the fortress were made. Much work had to be done in order to be prepared for a siege. For example, the beds of the mortars near

the Landpoort had to be improved, and about a hundred palisades at the Oostbeer and Westbeer had to be replaced. Colonel Schepern had also other problems to cope with.

On the 16th the naval Captain Van Capelle arrived in Willemstad, with orders to bring all ships and boats over to the northern side of the Hollandsch Diep, to prevent these being used by the French. Colonel Schepern however was of the opinion that this order did not include the ships in the harbour of Willemstad, because they were inside the fortress. In addition, he wanted to keep them, to be used for supplying Willemstad or to leave the fortress when needed. He managed to convince Van Capelle, who agreed. On 20 February orders were issued to the civilians in case the French would arrive before the fortress. In case of the alarm sounded, everyone had to stay inside his or her house. Only able-bodied men were allowed on the streets, including the men incorporated in the fire brigade. The fire brigade could make use of two fire engines: one from the Dutch Government, and one from the city itself. On the same day, an officer of the Regiment Saxen-Gotha arrived from The Hague, bringing with him orders to inundate the surrounding polders, which would take two days to complete.

The same day, the sluice of the Ruigenhil polder, called ‘Bovensluis’, which left out the excess water at low tide, was prepared for the inundation. The sluice had two pairs of doors. The outer doors, to be closed at high tide, were removed entirely and brought into the fortress. The inner doors, which were normally closed at high tide and opened at low tide to leave out the excess water out of the polder, were closed, barred and bolted with a big French padlock, and as such a beginning was made with the inundation.

On 21 February both inundation sluices, one located inside and one just outside the fortress, were opened to flood the polder. To prevent any surprise-attack on the fortress, from 21 February on, during the nights, a detachment consisting of a sergeant, a corporal and six soldiers, patrolled the surroundings of the city. On the same day, Captain of the Engineers Berg marched out with a detachment of labourers to bar the metalled Straatweg leading to the Landpoort of the fortress with abatis. [5]

He was protected during his labour by an infantry detachment consisting of two sergeants, two corporals and thirty soldiers of the Regiment Saxen-Gotha, commanded by the Ensign C.H. Schober of the same regiment. The French did not disturb the labour, and only a scout was detected, who managed to escape.

Also on 21 February intelligence was received that the French had occupied the village Fijnaart and the hamlet Oudemolen, southeast of Willemstad. In the evening, the Lieutenant Colthof was dispatched to Klundert to exchange intelligence with the commander at Klundert, Captain von Kropff. Choosing the safest way, Colthof left by boat, sailed by a ferryman, intending to land at the Noordschans, an entrenchment on the south bank of the Hollandsch Diep, north of Klundert, to go on foot to Klundert from there. However, arriving near Noordschans they met a Dutch bomb ship patrolling there, and after conferring with its Captain it was agreed that he would take care of bringing Colthof ashore, using the bombs’ own boat, manned by Lieutenant van den Bosch with four sailors. Arriving at Noordschans and coming ashore, Colthof and the crew of the boat were surprised by the French, not knowing that in the meanwhile Noordschans was occupied by them. Lieutenant van den Bosch and his sailors were taken prisoner and their boat captured.

Lieutenant Colthof however managed to evade capture and jumped into the reed. Pursued by the French he managed to escape, wading through the water up to his neck, in the direction of Willemstad. Managing to put some distance between himself and his pursuers, after a while Colthof heard the noise of a boat on the Hollandsch Diep. Presuming it had to be Dutch, he called out to the boat, which appeared to be the boat from the ferryman who had brought him from Willemstad. After Lieutenant Colthof had been picked up, both arrived in Willemstad again safely.

French Arrive in Force

During the following days, the French arrived in force outside the fortress. Their movements were much hampered by the inundations, and had to take place mostly along the dikes. The problem however for the Dutch was that the ‘Bovensluis’, which as we saw left out the excess water at low tide, was a half hour away from the city. The garrison was not strong enough to guard this sluice, and therefore the French, wanting to undo the inundations, met no opposition when they took possession of the sluice and managed to force the padlock.

They opened the inner doors at low tide, leaving the water out of the polder. As a result the inundations could become not complete and not deep enough to prevent French movement through the polder totally. The only solution that Colonel Schepern and Captain Berg saw was removing at least one of the inner doors entirely. Three citizens of Willemstad volunteered to try to accomplish this, and around half past seven in the evening they left the harbour in a small boat, taking with them the necessary tools. It was a dark night, and the men managed to reach the sluice unnoticed by the French, and after binding a long rope to a tree, in order to be able to return counter-current when the doors would be emoved and the water would flow into the Polder, entered the tunnel leading to the inner doors. After reaching the doors theymanaged to remove one of the doors out of its hinges, which floated into the polder and then sank to the bottom. The French were very surprised in the morning when they found one door missing, and were never able to prevent the water flowing in and inundate the polder.

The abatis on the Straatweg not finished; on Saturday 23 February at five o’clock again a detachment of labourers marched out of the fortress to complete the work. The detachment was covered by infantry consisting of two sergeants, two corporals and twenty-four soldiers of the Regiment Saxen-Gotha, commanded by Lieutenant J.R. Bellamy de Gallatin. The Lieutenant had, taking in account the weakness of the garrison, received specific orders not to engage in any combat with the French, but Bellamy was imprudent enough to put his outposts much to far forward. At once, a few of these were attacked by a French cavalry patrol.

Outposts Fall Back

The outposts fell back, firing at the French, while Bellamy advanced with his main force in two lines, to cover their retreat. The Dutch managed to fire two volleys at the French, which were reinforced substantially, killing an officer and eight troopers. The Dutch were outnumbered, Bellamy was surrounded and taken prisoner together with four of his men, while the remainder made good their escape by taking flight into the reed and marshes east of the fortress, and finally managed to reach Willemstad again. One of the sergeants was however severely wounded by a sword cut on his head. During the fighting alarm was given in the fortress, and a force consisting of two NCO’s and forty soldiers, commanded by a captain, was send to support Bellamy. However, because of the distance that Bellamy was from the fortress they came to late, and they only served to cover the retreat of the labourers, supported by gunfire from the fortress.

The alarm and the resulting gunfire from the walls caused a panic amongst the citizens of Willemstad. Colonel Schepern gave permission for all women and children, which choose to do so, to leave the city, but he also ordered that all male had to stay, although later it would become clear that some of them secretly also had left, including the lock-keeper! The arrival of reinforcements that evening, consisting of both grenadier-companies of the Regiment No. 8 Bosc de la Calmette, revived the spirits of the citizens. The 66-year old major-general of the

Infantry baron Carel van Boetzelaer followed these troops, becoming Governor of the fortress and taking over command of its garrison. A good choice, as we will see. Forty men of the Regiment Saxen-Gotha were transferred to the command of Lieutenant Colthof, to make up the shortage of artillerymen. Colthof managed to train these infantrymen in fourteen days to so well that they served outstandingly as gunners.

On the next day, Sunday 24 February, Major-General van Boetzelaer called together a council of war, to make plans for the defence

of the city. It was decided that a manor house situated at the Oostdijk, also a manor house at the Westdijk, and in addition a huge barn at the same dike, would have to be destroyed to prevent these being used for cover by the French. The order to fulfil this task was given to Lieutenant C.J. de Brauw from the Regiment No. 8 Bosc de la Calmette, and the Ensign C.F. Buchel from the Regiment Saxen-Gotha, with a detachment

consisting of two sergeants, two corporals and forty soldiers. Leaving the fortress around six o’clock in the evening the same day, at a given signal al these buildings were torched, and although pursued on the Oostdijk by some enemy patrols the detachments arrived safely in the fortress again, covered by gunfire from the walls. In addition at the Waterpoort, the bridges were removed and the gate closed and barricaded.

Bombardment

The following day on Monday 25 February, the bombardment of the fortress-city Klundert was heard by the citizens, and observed from the church tower and the windmills in the city. Knowing that the garrison of Klundert was very small it was estimated that it would take not long for

the French to capture the fortress. This became clear already the next day, when French colours were seen flying on the tower and the windmill at Klundert. It was expected that the French would now turn their attention to Willemstad, and indeed the same day French cavalry patrols were observed, which were promptly fired upon with the guns from the wall, in order to keep them as far away from the fortress as possible.

The garrison was busy strengthening the defences, improving the palisades and clearing fields of fire. The roof of the powder magazine was covered with manure to protect it against bombs. Vice-Admiral van Kinsbergen arrived and inspected the defences, together with the Governor Van Boetzelaer. On the following day, 27th February, around noon a trumpeter arrived at the Oostbeer, demanding to speak with the Governor of the fortress. When Major-General van Boetzelaer arrived, he was bluntly asked by the trumpeter, in the name of General Dumouriez, if he was prepared to surrender the city, yes or no! Van Boetzelaer was very angry about the way this question was asked, by a trumpeter not even accompanied by an officer, and only verbally, not in writing! So Van Boetzelaer’s answer was a short: “no!”, after which the ‘negotiations’ were over. On the same day at around seven o’clock in the evening, French cavalry and light infantry advanced along the Westdijk. Alarm was given and the guns on the wall opened fire, assisted by gunfire from the guard-ship ‘De Zeehond’. [6]

On 28 February at ten o’clock in the morning Gazin, aide de camp of adjudant général Berneron, accompanied by a trumpeter, arrived before the fortress on the Westdijk, waving with a white handkerchief. Arriving near the guard they declared that they wanted to enter. Receiving message of their arrival, Major-General van Boetzelaer ordered Lieutenant Johan Frederik Lang, who was Sous-Major of Willemstad, and the Ensign Carl Heinrich Wilhelm Anthing from the Regiment Saxen-Gotha, to go outside and to escort the French officer inside blindfolded. Entering the fortress near the Waterpoort by boat (because the bridges were removed and the gate closed), the officer was brought to Van Boetzelaer, residing in the ‘Prinsenhof’. Although it was expected that again the surrender of the fortress would be asked, it soon became clear that the French officer had another mission to accomplish.

With him he brought a letter from adjudant général Berneron, saying that he believed that the Dutch took prisoner a missing officer of the engineers. Because of the fact that this engineer was a protégé of Berneron, he proposed to exchange him against Lieutenant Bellamy, who as we have seen was taken prisoner on the 23rd. In the meantime, Van Boetzelaer had no information about a French officer taken prisoner, and was of

the opinion that this mission was only a trick to be able to enter the fortress to spy, and to ascertain with what kind of Governor the French had to deal with. Not a word was spoken about surrendering the fortress to the French, and the officer left empty-handed the same way he came, returning again the same day at around five o’clock in the afternoon. Entering the fortress the same way as before, this time he had a more

serious mission, bringing with him a letter from Berneron, who asked him to surrender. I think the contents of this letter and others are interesting enough to translate them as a whole, because it will give you a good ‘feeling’ of how the situation was:

Before Willemstad, 28 February 1793, the second year of the Republic.

My Lord!

I have orders to attack the place you command; the means that I possess to reach this goal, are twofold from what I need, to bring you down, and if these means would be exhausted, they would immediately be replenished by those who are behind me and within my reach. From this sketch, which is not exaggerated, you must understand that all resistance from your side is senseless.

Save yourself the regrets that is being prepared by your foolish obstinacy: open your eyes and take a look at the people and property that is entrusted to you, and try to save them and to act humanly, instead of being bold without results.

I have pity with the wretched situation in which I found the inhabitants of Klundert; they will curse their foolish commander forever, who brought so much misery upon them because of his stubbornness, with results they will suffer for a long time. Beware yourself, my Lord! For the same reproach from those, whose father you must be!

The French are only at war against tyranny: they are the brothers and friends of all humans, and are only aiming at their welfare and happiness. This is the object of all their labour; woe betides the men! who feed the hope, to oppose such laudable objects!

Until now my Lord, I have spoken to you the language of the reason; because I hold you for a wise and human person; but if you, against my expectations, force me to use the power and the means that I have, you will pay with your head surrounded by the ruins and flames, for the disasters that you have caused to happen by your own doing.

When I became master of Klundert, I heard that the commander had sounded the retreat; but the wind and the noise of my batteries prevented me hearing this: this unforeseen event was the cause for even more misfortunes. To prevent the same thing happening between you and me, let us agree that, if we would start a fight against the wish of my heart, and you would like to end it, you can let me know your

intentions during daylight by hoisting a white flag, and during the night by lightening three fires next to each other.

I finish my letter my Lord, by telling you that by making this letter known to all, as well as your answer, will justify the disasters that will happen, in the eyes of the reasonable ones, as well in the eyes of the military scientists. Waiting for the moment to meet you in person, and assured from my deepest regards,

(signed)

The Marechal de Camp. [7]

P.S. I have the honour to inform you, that today Geertruidenberg and Steenbergen are attacked.

The postscript about the fortresses Geertruidenberg and Steenbergen was a mere bluff, but Van Boetzelaer did of course not know this. Although Geertruidenberg surrendered on 4 March, the Dutch as well as the French did not anticipate this. Steenbergen was an entirely different matter. A much to small garrison defended Steenbergen, what after my previous articles cannot come as a surprise. Colonel Johan Christiaan Frederik Schmidt commanded at the fortress. On 25 February Colonel Leclaire demanded the surrender of the fortress, which was refused, Colonel Schmidt stating that he would defend Steenbergen as a man of honour. When the French tried to construct a battery they received heavy gunfire from the walls and ceased construction.

From then on, only French patrols were observed in the vicinity of the fortress. Steenbergen had no tactical value for the French, which had passed it on the way north, and was only held under observation. However, Van Boetzelaer gave Berneron the following answer, with

which Gazin left again, short but very clear:

My Lord!

In answer to your letter, with which you did me much honour in writing it, I have the honour to inform you that I, as a man of honour, will defend the place entrusted to me; without noticing any objections what however.

Being with much consideration, My Lord!

Your Honour very submissive servant,

(was signed)

During the afternoon more reinforcements were disembarked: a detachment of the Regiment Saxen-Gotha which had been detached to Goedereede, consisting of an officer, a sergeant, two corporals, nineteen soldiers and a drummer; and six musketeer companies of the Regiment No. 8 Bosc de la Calmette commanded by Colonel Willem Spiering (van Beloys) and Major Pieter van Nievelt, arriving from Rotterdam.

[8]

The Governor van Boetzelaer assigned the following posts to his officers. Colonel Commander Schepern from the Regiment Saxen-Gotha would be his second in command. Colonel W. Spiering van Beloys from the Regiment No. 8 Bosc de la Calmette received command of the Waterpoort, the Westbeer and the ‘Gelderland’ and ‘Holland’ Bastions. Major van Nievelt from the same regiment, serving as General

Adjutant from Van Boetzelaer, commanded in addition the courtine between the ‘Holland’, ‘Zeeland’ and ‘Utrecht’ Bastions, and the ‘Zeeland’ Bastion itself. Major G.H. von Nitzschwitz from the Regiment Saxen-Gotha commanded the ‘Utrecht’ and ‘Friesland’ Bastions, up to the Landpoort. Lieutenant-Colonel Christian Ludwig Teutscher von Lisfeld from the same regiment commanded at the Landpoort, the Oostbeer, and the ‘Overijssel’ and ‘Groningen’ Bastions.

Further, it was ordered that during the night, except for the ordinary guard and the piquet, of each company an officer, an NCO and a third of the soldiers would stand guard on the walls. In case of an alarm, the garrison would collect at and defend the following parts of the fortress: two grenadier-companies, one of the Regiment Saxen-Gotha and one of the Regiment No. 8 Bosc de la Calmette, at the ‘Gelderland’ bastion and the Westbeer; the other grenadier-company of the Regiment No. 8 Bosc de la Calmette at the Oostbeer; two musketeer companies at all the other bastions, one of the Regiment Saxen-Gotha, and one of the Regiment No. 8 Bosc de la Calmette. As already told, to remedy the lack of

artillerymen men and officers of the infantry were detached to serve with the guns on the walls. Sous-Lieutenant T.C. Esau of the 2nd bat/Regiment Saxen-Gotha [9] received command of the battery at the Westbeer. Lieutenant G.W. Stahl van Holstein from the Regiment No. 8 Bosc de la Calmette commanded the battery at the Oostbeer. Corporal Hausdorff of the Regiment Saxen-Gotha, having artillery experience, received command of the howitzers on the ‘Gelderland’ Bastion. All three would serve with distinction.

Klundert and Willemstad 1793 Dutch in Revolutionary Wars Part 9

The Dutch During the Revolutionary Wars

|