Skirmishing and

The Third Rank

Part 2

The French and British

French

by John Cook, UK

| |

The extraordinary thing about the French is that of all the nations involved in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, the one which has the greatest reputation where skirmishing is concerned, has left us least on the subject in any of their official documents and we have to rely on 'snapshots' of tactical practice in the writings of eye-witnesses, and the analysis of secondary authorities. One begins to wonder if there is just the possibility of another Napoleonic myth here. The French Règlement 1791 specifies three ranks. The tallest men were placed in the first rank and the smallest in the second, the remainder made up the third rank. The Règlement 1791 also says that "when the troops are on a peace time footing, and exercise by battalion, the peletons will fall-in in two ranks, to increase the frontage to that specified for three ranks on a war footing." [64] It further states that when the frontage of a peleton was reduced to less than twelve files, it was to employ two ranks. It is clear that battalion frontages were important to the French too, and that they were also perfectly capable of adopting two ranks to extend the front if necessary.

We have already seen that Scharnhorst alluded to the "awkwardness of the first rank kneeling". Ney likewise commented on the utility of the third rank and the problems with a kneeling first rank. He noted that once the first rank had knelt it was very difficult to get it to rise to reload, as doing so exposed it to enemy fire. He also noted that a kneeling front rank prevented a quick charge with the bayonet. Writing in approximately 1805, he stated "There are but few instances to be cited during the last war, in which direct firing, according to this system, has been executed with any great success." [65]

The Règlement 1791 also specified two rank firing, in which all three stood, the third rank loading muskets for the other two. Ney notes that the firing of two ranks is "absolutely the only kind of firing which offers much greater advantages to the infantry than those above mentioned." However, he also says that it proved very difficult to get the third rank to part with their muskets, and the other two ranks had little confidence in firing weapons they had not loaded themselves. In practice, the third rank retained its own weapons and did not take part in firing, being held in reserve. "This imperfection disappears when firing is confined to the first two ranks, the third porting arms and remaining as a reserve to be used according to circumstances." [66] It is possible to conclude, therefore, that the French, in common with trends elsewhere, may also have used a two rank firing system from at least the start of the Imperial period, where the first two ranks delivered musketry from the standing position and the third took no part.

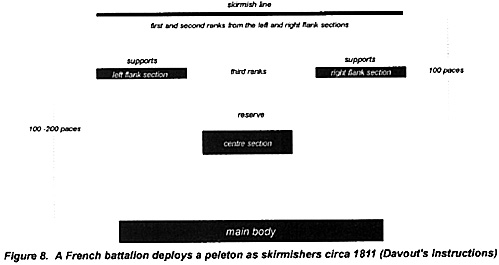

The Règlement 1791 has little to reveal about how the French skirmished but if Davoût's instructions are typical of the Imperial period, they show a similar arrangement to that which we have already examined in the context of the Prussians and Austrians, that is to say a dispersed skirmish line, a reserve and supports. The detached peleton was divided into three parts, a right and left wing and a centre. The first and second ranks of the two wings deployed in dispersed order to form the skirmish line, in an arc between approximately 100 to 200 paces to the front of the parent battalion, with the third ranks of the wing sections as supports to the dispersed element, behind which stood the centre element in three close-order ranks in reserve (Figure 8 see below).

John Lynn's study of the army of Revolutionary France shows that French skirmishing was not necessarily the undisciplined activity it is sometimes portrayed as. The bulk of his evidence indicates that skirmishing was the domain of the most experienced soldiers and battalions, rather than the worst, and that it was conducted in a disciplined and controlled way. This is supported by his statistical analysis of 85 examples of infantry in the light role, which shows that total dispersal of the detached units only occurred on ten occasions. [67]

Unless a system of some description existed, undisciplined skirmishing, without a reserve, and supports on which the skirmishing element could rally, the whole process must have devolved into a mob in which the committed units would probably be lost for future use and, furthermore, would have been left very exposed. If there was an official doctrine for disciplined use of skirmishers in the French service, it seems to have been largely unrecorded.

More Skirmishing

Footnotes[64] Reglement das Exercitium und die Manövres der Französischen Infanterie betreffend vom 1sten August 1791. Braunschweig, 1812. p5. German language edition of the Règlement 1791 for the Westphalian army.

|