Skirmishing and

The Third Rank

Part 1

The Prussians and Austrians

Prussians

by John Cook, UK

| |

Here is a notion that the content of drill regulations had little or no application beyond the parade ground, that it was ceremonial or largely theoretical and, therefore, was not relevant to the practicalities of the Napoleonic battlefield. Where this impression has come from is not clear because far from containing abstract rituals, the regulations described the battle-drills units were expected to use in combat.

Whilst it is certainly possible to concede that one unit might well be less well trained than another, and often was, without knowledge of the principal battle-drills contained within the regulations, it would have been impossible to preserve order in an environment dominated by extremes. An untrained unit, therefore, would have been useless in all but the most primitive of tactical settings.

Although the close-order nature of the Napoleonic battle-drills meant that there was little opportunity for leaders at the lower levels of command to exhibit very much tactical flair or creativity, an exception to this was skirmishing.

The contentions of Paul Thompson's wargaming friends (ADC FE34) that the Prussians rarely deployed skirmishers in any numbers, and that the Austrians never employed two ranks, are curious ones to peddle because there is no evidence to support them. It would be useful to know where they got their information from. All the evidence shows that in addition to providing skirmishers, which was done routinely and in similar fashion to methods elsewhere, the third rank in the Prussian and Austrian service was also used to extend the line when a unit was not sufficiently strong to cover the required frontage and, furthermore, was also required to carry out a number of other detached roles, all of which reduced the battalion in line to two ranks.

Although it is probably true to say that the British made more use of two ranks as a matter of course, the belief that they were unique in this context is incorrect. Scharnhorst, in his first essay On Infantry Tactics, notes "In a formation of three ranks, the length of the musket employed enabled all ranks to fire standing up". Whilst acknowledging that the front rank usually knelt to allow the rear ranks to fire more easily, he also says that during the "French Revolutionary War, in 1794, the awkwardness of the first rank kneeling when all three ranks fired, and growing tendency to extend fronts to outflank the enemy, led occasionally to infantry formations of two ranks." [1]

Here is unequivocal evidence from a contemporary witness, which shows that the Prussians were quite capable of employing two ranks to extend the line, when tactically expedient, from the very earliest part of the period.

How they went about converting from three to two ranks at this early period is difficult to answer because although the Reglement für die Königlich Preussischen leichte Infanterie 1788 is said to be essentially the same document as that used by the musketeers and grenadiers, the fusiliers at that time employed two ranks and, therefore, their regulation is not much help.

However, to further expand upon Peter Hofschröer's notes in FE34. Although according to Paret "the army was flooded with drill manuals, as well as 'private regulations', written by a regimental commander or a member of his staff, and designed for one particular unit, or inspection" [2] during the last years of 18th Century, the Reglement 1788 remained current until 1806, albeit modified by a number of interim regulations and instructions. [3] One of these was the Instruction zum Exerciren der Infanterie 1798, which gives some details in the context of the use of the third rank.

The introduction to the Instruction 1798 certainly confirms the disparity between inspections and regiments and Frederick William III states, "On this account I have judged it advisable to revise once more the regulations of all the troops to determine and establish each point in the clearest manner." Nevertheless, the Instruction 1798 is a slim document which does not appear to be sufficiently comprehensive to stand alone. It is also clearly an interim publication providing details of revisions to the existing regulations, presumably the Reglement 1788.

It was published, apparently, pending the introduction of new regulations and "for the sake of uniformity", the absence of which the king complained, and wished to correct. He closed the introduction by giving an unambiguous command for the instructions "punctual observance". Presuming that the king's order was obeyed, the Instruction 1798 may give an additional insight into the way the Prussian infantry fought during the period up to 1806.

In the Instruction 1798 the infantry continued to employ three ranks, and as far as skirmishing is concerned it does not alter the provision of a skirmish element from the third rank, which consisted of 10 rifle-armed Schützen in each company. Some modern commentators, probably influenced by accounts of masses of French skirmishers, have implied that this skirmish element was too small to be effective. We shall see that this is not necessarily the case and in terms of numbers it was not untypical.

Musketry is described being delivered by three ranks and by two ranks. Firing whilst advancing or retiring was delivered by three standing ranks. [4] When stationary, however, the front rank knelt with the butt of the musket placed against the knee, and musketry was delivered by the second and third ranks alone. [5]

Similarly, when a battalion was attacked by cavalry, whether it was in square or otherwise, the first rank was instructed to kneel, bracing the butts of their muskets on the ground, whilst only the second and third ranks fired. [6]

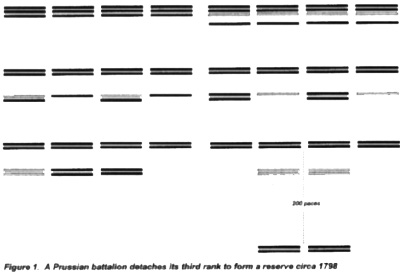

Elsewhere the Instruction 1798 describes how the third rank of a four-company battalion could be used to form a reserve if required. This was done from the battalion in line. The third rank executed an about-turn and was retired fifty paces, where it halted and was placed in the advanced position by a another about turn. It was then formed in two ranks thus.

The third ranks of the fourth and second companies took one pace to the rear and the third ranks of the third and first companies filed in front of them. The two companies, each of two Züge, then closed on the centre creating an ad hoc battalion two ranks deep, commanded by the senior captain (Figure 1 at right). [7]

It seems that the last part of this evolution is somewhat unnecessary. The flanking third ranks could have filed left and right, in front of and behind the centre third ranks respectively, thus removing the need to close on the centre and, therefore, saving time. The Instruction 1798, however, is quite clear.

The precise use of this reserve battalion is not given except to say that it was a reserve "which generally remains in the second line with an interval of 200 yards from the (parent) battalion". As a reserve it could have been put to a number of different uses including, presumably, being brought forward to extend the line in two ranks if necessary, as alluded to by Scharnhorst. I must admit, however, that I cannot provide further evidence of that in practice. Furthermore, in 1799, the Prussian infantry regiments were reorganised into five-company battalions and how this reserve was formed from the third ranks of five companies, which would have produced two-and-a-half companies (five Züge), is not evident.

Nevertheless, as far as skirmishing is concerned, there is evidence documented by Jany which shows that during the 1806 campaign the reserve formed by the third rank was used for this purpose. Units under command of GM von Sanitz detached their third ranks to reinforce their Schützen at Jena (this officer commanded grenadier battalions in the Reserve Division of Hohenlohe's army). "General von Sanitz had reserves formed from the third rank of the corps and threw them into the wood too".

Jany also demonstrates that an entire company could also be dispersed for the same purpose if need be. IR 23 von Winning, in the absence of its Schützen, detached a musketeer company to cover its retreat at Jena [8], "1st Lt von Wobeser" was ordered "to cover the retreat with his company, and this he did as well as he could with musketeers operating 'à la débande'." IR 28 von Malschitsky, in the absence of its Schützen which were on patrol duties elsewhere, also detached a musketeer company as skirmishers at Auerstädt; "due to the lack of Schützen, the left flank company was used for that purpose." [9]

It is of possible significance that the grenadier battalions, which still consisted of four companies, are recorded apparently using the reserve formed from their third ranks as skirmishers, whilst the infantry regiments, which comprised five-company battalions since 1799, appear to have detached entire companies as skirmishers. It may be that the difficulty presented by an odd number of companies, alluded to above, was such that reserves were not formed from the third ranks of infantry battalions in 1806.

The evidence I have in this context, however, is too circumstantial and limited in scope to form any definite conclusions but Jany is quite clear that the use of either the third rank or an entire company for skirmishing, as appropriate, had become typical by 1806 and his examples were representative of standard tactical practice. Furthermore, the incontestable evidence of primary sources demonstrates that the Prussians, even in 1806, were not so inflexible as modern popular writers sometimes portray them.

Concurrent with the post 1806 reorganisation, new regulations started to appear. The Instruction Über den Gebrauch der dritten Gliedes 1809 (Instruction Concerning the Use of the Third Rank 1809) appeared in March of that year. Paret attributes it to Gneisenau but Jany states that the first indication that the Prussian army as a whole, rather than the practice in individual inspections, was moving to a doctrine where the entire third rank was to become the source of the battalion's skirmish element dates from July 1807. This, apparently, was in Frederick-William III's own hand and was confirmed by an Order-in-Cabinet dated 20 November 1807. [10]

As we have already seen, the Prussians had already been using the third rank for a variety of special purposes and, in addition to Scharnhorst's observations on practices in 1794, it is worth mentioning that Hohenlohe had also documented separate roles for the third rank in his Instruction of 27 April 1797, and had introduced a specific Instruction concerning the use of the third rank for skirmishing in his Silesian inspection in 1803. So, although the link between Hohenlohe's Instructions of 1797 and 1803 and the Instruction Über den Gebrauch der dritten Gliedes 1809 is, perhaps, more tenuous than Paret suggests, taken overall it is certainly possible to detect a continual development in Prussian tactical practices.

The Instruction Über den Gebrauch der dritten Gliedes 1809 deals specifically with the functions of the third rank which is given five specific roles: [11]

The Instruction zum Exerciren der Infanterie 1809, which appeared in July 1809, states that the third rank no longer fired and, therefore, that it was no longer necessary for it to close up. [12] The use of the third rank for firing had been largely discontinued everywhere, as had kneeling by the first rank.

So, to return to the Prussian line infantry regiment, which now consisted of three battalions, two of musketeers and one of fusiliers. The Prussian infantry continued to fall in three ranks, but the third rank was no longer employed for musketry. It is important to note that the Instruction 1809 applied to the line infantry generally, not just the fusiliers. According to Paret, this document was written by a light infantry expert and protégé of Scharnhorst, Major Johann Krauseneck. It specifies quite clearly that the third rank was responsible for provision of the skirmish element. [13]

Of further significance is the final part of this document which provides orders for the use of infantry in the light role. Again, the instruction applies to musketeers and fusiliers alike. [14] This is important for it indicates that the Prussians have started to embrace the concept of the universal infantryman, capable of functioning equally well in two or three close-order ranks, or dispersed as a skirmisher.

These two instructions of 1809 were followed by specific instructions for the training and employment of Jäger, Schützen and fusiliers, written by Yorck and promulgated in 1810. According to Paret, these were approved by Frederick William III on 29 March 1810, but with the exception that the fusilier battalions should not, as Yorck had recommended, employ two close-order ranks like the Jäger and Schützen, but three close-order ranks like the rest of the line infantry. [15]

The instructions describe a two-rank dispersed skirmish line and say that the light troops provided security for an army, covering its movements in the attack and blunting the attacks of the enemy. Specific roles were given as outpost duty with sub-units of advance and rear guards, patrolling, direct and indirect tactical co-operation with the operations of the army and, finally, detached and special operations as part of the strategic plan. [16] The instructions state that fusilier battalions are required to fight in close-order line, as well as dispersed order, and that the Jäger and Schützen were also to acquire the principal elements of duties in close-order line. [17]

The Exerzir-Reglement für Infanterie der Königlich Preußischen Armee 1812 continued the trends already established since the post 1806 reforms and confirmed the letter and spirit of the Instruction 1809. The Exerzir-Reglement 1812 states, like its predecessors, that the infantry employed three ranks. [18] If one was to read no further, it would be possible to infer that a three-rank line was the end of the matter. However, for musketry, like the Instruction 1809, it reiterates that only the first and second rank fired. The second rank took a pace to the right, so that it could fire through the gaps in the first rank, whilst the third rank took a pace backwards and stood fast. [19] The respective roles of the ranks are clear "The largest (men) form the first rank, the most nimble and best shots are selected for the third rank." [20]

This is all unequivocal evidence of a two rank firing system with the third performing a supporting role. It also shows, by the types of soldiers selected for it, and from the instructions specific to it, that the third rank provided the skirmishers.

The roles of the skirmishers in the Exerzir-Reglement 1812 are the same as those in the Instruction Über den Gebrauch der dritten Gliedes 1809, except that, "Filling intervals when there are insufficient troops to cover the frontage in close order" is omitted. I do not really know what conclusion one should draw, if any, from this apparent omission. Perhaps it was so obvious an instruction it didn't bear repetition.

Of particular interest are the orders for General Use of the Third Ranks at the start of Part Four to the Exerzir-Reglement 1812. These are essentially the same as in Scharnhorst's second essay On Infantry Tactics, and the Instruction Über den Gebrauch der dritten Gliedes 1809. They state that "The infantry must be able to fight in open and irregular country against dispersed and close-order troops. Every isolated part, battalion, company and so on has its own detachment for close and dispersed fighting; for the former it is the first and second (ranks), for the latter it is the third rank." [21] This echoes Scharnhorst, "When a company is detached from the battalion, or even separated for a moment, it takes its skirmish section along. No battalion, no company, no section moves without its skirmishers." [22]

The orders go on to say that the nature of the close-order detachment meant that its greatest value was in massed fire and bayonet attack, the detachment for dispersed combat being best employed for independent fire, using the terrain and taking advantage of the movements and dispositions of the enemy. It then says, and this is important, that both detachments must be able to undertake the missions of the other, "both front ranks need to be able to be dispersed if necessary, and the detachment of the third rank able to fight in close-order." Thus, we have confirmation that the Prussian line infantry, as a whole, was expected to function in either the skirmish or close-order role if required to do so.

The orders close with a brief summary of roles other than skirmishing for the third rank, which are as an advance-guard, a rear-guard, a flank-guard, a reserve and in support. [23] Part Four also describes specific dispersed order roles for the third rank, which are essentially the same as the Instruction 1809. [24] It is evident, however, that the third rank was required to fulfil a variety of roles, in addition to skirmishing.

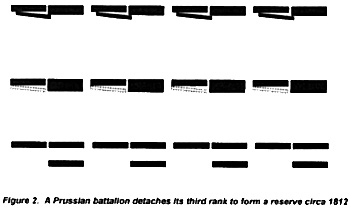

The procedure for detaching the third rank was conducted by means of a doubling procedure, similar to that for forming in two ranks in the British Rules and Regulations 1792 discussed later, except that the right flank Züge became the rear rank, rather than the front, and the evolution did not involved a file march to the flank, because the intention here was not to form an extended two rank line specifically. The evolution was carried out with the battalion in line and on being given the order to form in Züge, the third ranks of even numbered Züge of each company of the battalion executed a right-turn and marched in file behind the third ranks of the uneven numbered Züge, thus forming an ad hoc reserve battalion of four Züge each formed in two ranks.

Section 9 to Chapter Two of Part Four to the Exerzir-Reglement 1812 describes the duties of the fusilier battalions. It is worth repeating the instruction in full:

"The fusilier battalions are intended principally for dispersed combat, they must be completely trained for this type of combat, and every fusilier fully skilled and trained in marksmanship. When fusiliers serve in conjunction with several battalions in the line, or a formed brigade, they use their third rank for dispersed combat as well; however where they are used for some special purpose, detached as an advanced guard, rear-guard, outpost duty and that sort of thing, the differences between the third rank and the other Züge of the battalion cease to apply. Every company must be formed in three Züge, each two men deep, employed turn in dispersed order. They are organised in the same proportion and pattern as the skirmish group from the three (sic) [26] Züge of the third ranks of a line battalion.

The battalion commander determines the positioning of the companies, and generally conducts their movements. The company commanders take advantage of the terrain in order to carry out their specialist role, they decide which Züge or sections are to be dispersed, used to reinforce or be withdrawn from the skirmish line in accordance with the course of the combat, select an advantageous position for the close-order Züge, from which they can easily support the skirmish line and so on."

"A fusilier company must be practised in forming a skirmish line from any close order deployment, and forming in line or column again. As a rule only one Zug is used at a time, however, special circumstances can give rise to an exception." [27]

The points to note here are fivefold. First, it confirms that the fusiliers employed three close-order ranks, not two as had been the custom up to 1806. Second, it shows that the fusilier battalions used their third ranks exactly like the musketeer battalions. Third, it shows that the fusilier battalions were intended for independent missions. Fourth, when a fusilier battalion was acting independently it broke down into individual companies, each of three Züge. Five, fusilier battalion and fusilier company commanders had considerable tactical autonomy, the latter deciding which sub-units they deployed dispersed and which they retained in close order as supports and reserves. [28]

Although the fusilier battalion was perfectly capable of functioning as part of the infantry regiment in either close or dispersed order, it was the brigade's primary light infantry asset. The third ranks of the musketeer battalions provided additional skirmishers, which would be needed if the fusilier battalion was on detached duty. A Prussian line infantry regiment, therefore, had in excess of half its establishment specifically trained and available for the light role. Thus every infantry formation and unit, from brigade (which equated to a division in Prussian service), through regiment, down to the smallest sub-unit of the battalion, had its own skirmish element with it at all times.

It is also clear that the Exerzir-Reglement 1812 intended the entire line regiment to function in either closed or dispersed order, in accordance with tactical circumstances. This, however, should not be interpreted as meaning that entire regiments dispersed as skirmishers as a matter of course.

The Exerzir-Reglement 1812 states that from a third to a maximum of two thirds of the element detached for skirmish duties was to be dispersed. [30]

The actual strength depended, of course, on that of the battalion in question. The third rank of a battalion at more or less full strength of 800 men would provide four Züge of approximately 66 men each. Of these, two Züge remained in reserve, which left two Züge for skirmishing comprising a total of approximately 132 men.

According to the parameters of the Exerzir-Reglement 1812 there would be, therefore, from approximately 44 to a maximum of 88 men deployed in dispersed order to the skirmish line.

In terms of numbers, the difference between the 44 to 88 musketeers of 1813 and the 50 rifle-armed Schützen of 1806, does not appear to be particularly great. The proportion of Prussians available for the skirmish line is also not significantly different from the 64 tirailleurs which Jean-Nicolas Houchard's instructions of 1793 stated should be drawn from each French battalion, [31] or the approximately 50 men in dispersed order from a skirmishing peleton (assuming a peleton strength of approximately 150) which one can extrapolate from Davoût's instruction of 1811. [32]

However, there are many examples of the French, apparently, deploying entire battalions as skirmishers, including grenadier companies, sometimes in what seems to be an uncontrolled manner. So, where a six-company battalion was detached in its entirely, perhaps to cover the movements of a brigade sized formation, further extrapolation points to a dispersed skirmish element of a minimum of approximately 300 men per battalion in that role. It is necessary to concede that the application of these extrapolated figures to an 1806 scenario, suggests the possibility of a local numerical Prussian disadvantage. By 1813, this has disappeared and a Prussian regiment of three battalions would, as we have seen, be able to produce approximately 260 men from its third ranks alone.

Be that as it may, it does not appear that the Prussians were decisively out-skirmished in 1806 or, indeed, that skirmishing in general was ever a deciding factor by itself. One suspects that popular history may have overstated the effect of French skirmishing to the point where it has become part of Napoleonic folklore in its own right.

A diagram of a Prussian brigade formed for an attack, at Plan II to the Exerzir-Reglement 1812, shows a fusilier battalion similarly deployed with the three familiar elements consisting of a close order reserve 50 paces to the rear of the main body, close order supports to the skirmish line approximately 100 paces in front of the main body, with the dispersed skirmish line at a similar distance beyond its supports (Figure 4).

To reiterate what Peter Hofschröer had to say about the Prussians during the later Napoleonic period, which is of particular interest to Paul. All Prussian line infantry employed three ranks when in close order, including the fusilier battalions [33]. The line infantry only used the first and second ranks for musketry, in keeping with trends generally. The third rank performed a supporting role and provided the skirmish element. All skirmish firing lines were deployed in a dispersed two-rank line. The role of the skirmish line may be summarised as follows.

In addition to the documents examined here, there is at least one other Prussian pre-1806 instruction and two additional post 1806 instructions that deal with the use of light infantry that I am aware of, but do not have access to. [34]

So there was, at the very least, a total of six Prussian regulations and instructions dealing with the specific uses of the third ranks, skirmishing and light troops, not to mention the parts of the regulations for the infantry in general which include passages on the subject. This by itself is inconsistent with Paul's wargaming friends' perception of Prussian skirmishing. The concept that the Prussians would go to the trouble of documenting the use of light troops in such a comprehensive manner if they did not intend to make use of them, does not seem very likely.

The evidence shows that from the very earliest part of the period there was an increasing deployment in two ranks or, more properly, the separate use of the third as a tactical option in a variety of circumstances. It is clear that by at least 1798 the Prussians had documented the beginnings of a doctrine for the use of the third rank for a variety of purposes, one of which was skirmishing. The evidence also shows that they put this into practice during the 1806 campaign. By 1810 they had developed it into a comprehensive system. Skirmishers from line battalions were used routinely in 1813, by which time the Prussians were well into the era of the universal infantryman.

More Skirmishing

[1] Scharnhorst. On Infantry Tactics. First Essay. Introduction to Infantry Tactics. 1811. Reproduced in Paret, P. Yorck and the Era of Prussian Reform. Princeton, N.J, 1966. Appendix 1. p255.

|

Each Zug was commanded by an officer and had three NCOs and a hornist. The reserve battalion was commanded, as before, by a captain (Figure 2). [25]

Each Zug was commanded by an officer and had three NCOs and a hornist. The reserve battalion was commanded, as before, by a captain (Figure 2). [25]

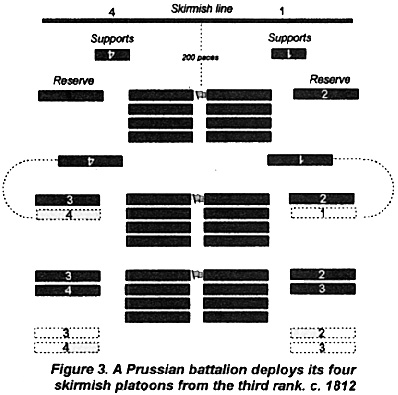

Herbert Schwarz shows how Prussian skirmishers were used (Figure 3). [29] The four Züge of the third rank formed into two, two Züge, columns approximately 50 paces to the right and left rear of the battalion. Two Züge of each column either remained to the rear or took up position on the flanks of the battalion, where they stood in two close-order ranks as a reserve. The other two Züge advanced in two close-order ranks to a position approximately 100 paces in advance of the battalion where a proportion remained in two close-order ranks as supports to the skirmish line, and the remainder deployed in dispersed order to form the skirmish line at a similar distance in front of the supports.

Herbert Schwarz shows how Prussian skirmishers were used (Figure 3). [29] The four Züge of the third rank formed into two, two Züge, columns approximately 50 paces to the right and left rear of the battalion. Two Züge of each column either remained to the rear or took up position on the flanks of the battalion, where they stood in two close-order ranks as a reserve. The other two Züge advanced in two close-order ranks to a position approximately 100 paces in advance of the battalion where a proportion remained in two close-order ranks as supports to the skirmish line, and the remainder deployed in dispersed order to form the skirmish line at a similar distance in front of the supports.