Skirmishing and

The Third Rank

Part 2

The French and British

British

by John Cook, UK

| |

No study of the use of two ranks, however cursory, would be complete without mention of the British. In 1788 a book called Principles of Military Movement was published. It was written by Sir David Dundas and, in 1792, it was published in abridged form as the Rules and Regulations for the Formations, Field-Exercise and Movements of His Majesties Forces 1792. Dundas' Principles are said to be a literal translation of a treatise by von Saldern [68] but this is questioned by Richard Glover [69] , who points out that von Saldern did not produce his own work until 1784 and Dundas' draft must have been written prior to 1785, because Dundas attended Prussian manoeuvres in that year and, by his own admission, revised his work as a result. It seems certain, therefore, that the two men wrote independently of each other.

Be that as it may, comparison of the Rules and Regulations 1792 with the Prussian Reglement leichte Infanterie 1788 and Instruction zum Exerciren der Infanterie 1798 shows that there can be absolutely no doubt that the fundamentals of the British document are derived from 18th Century Prussian methods. This should be no surprise. Dundas served as a regimental officer in the 1760s during which time he saw sufficient active service to suppose that his writings were based on experience. The dominant military power at the time, and the one to which most looked for the secret of success on the battlefield was Prussia. Under the circumstances, it would be extraordinary for anybody to depart from the essentials of Prussian practice or, more significantly, that the military establishment would accept the validity of a document that did.

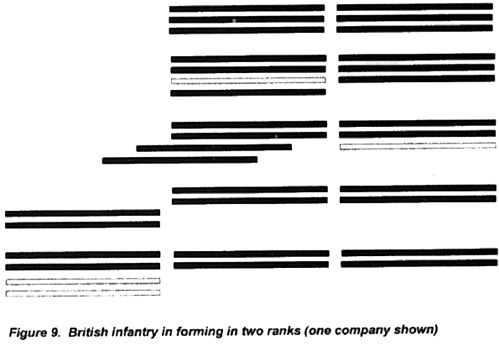

The Rules and Regulations 1792 requires the infantry to fall-in in three ranks [70] . To form two ranks a doubling procedure was used. The third rank of the left sub-division of each company stepped back one pace. The third ranks of both sub-divisions then executed a left turn and marched off in single file, the left stepping short until the right had drawn level with it to form the front rank of the new sub-unit, which marched in file until it had cleared the left flank of the company, where it halted, executed a right turn and dressed on the company's left flank (Figure 9).

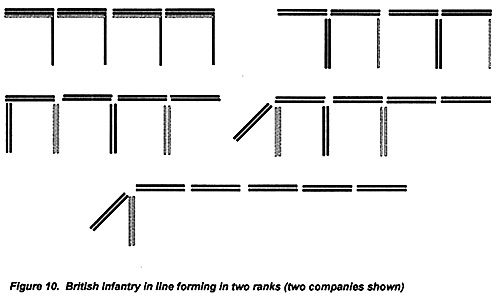

This manoeuvre was executed from open column and increased the frontage of each company by one third. When in line, unless gaps had been left between companies, it is evident that this was not possible. In this case, the third rank of each company first wheeled back by sub-divisions, each then closed up forming a column of sub-divisions open to deploying distance, which marched off, wheeling into line one after the other on the flank of the battalion (Figure 10).

It is possible, and I stress that this is no more than speculation, that the Prussians formed two ranks in much the same way in their Reglement Infanterie 1788.

For comparative purposes it is of interest to take a brief look at skirmishing drills as described in the British Rules and Regulations 1792.

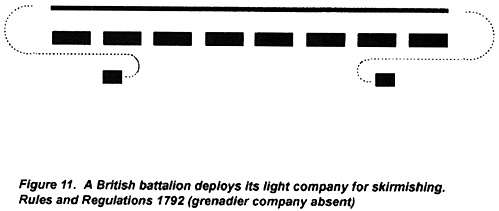

When deployed for skirmishing duties, the light company of a British infantry battalion was divided into a left and right division. Both stood thirty paces behind the parent battalion, the right division in rear of the second company, the left in rear of the seventh company. When ordered to cover the line to the front the two divisions wheeled round the flanks of the battalion by their inner flanks (avoiding inversion), to meet opposite the centre of the battalion, opening files from the rear "so as to cover the whole extent of the battalion" at a distance of 50 paces (Figure 11). [71] Elsewhere the Rules and Regulations 1792 specified that a proportion of the light company should be retained "as a reserve on which those detachments may fall back". [72] This proportion, however, is not specified and does not appear to have been mandatory.

This is pretty standard stuff, and more or less parallels other contemporary British documents on the subject. In general, however, the instructions are somewhat vague compared to some others, and the Rules and Regulations 1792 seems to keep skirmishing elements somewhat closer to their parent battalion than was usual elsewhere.

George Nafziger discusses additional British material on skirmishing, of which perhaps Rottemberg's is the best known. This document also describes the division of the light company into two parts but in this case advises that only one part be deployed to the skirmish line, the other retained formed as a support behind it. Again, however, this was not mandatory and complete deployment to the skirmish line was allowed. As far as skirmishing is concerned, none of this material appears to add much to what is specified in the Rules and Regulations 1792. [73]

The Rules and Regulations 1792 says that when "grenadier or light companies are detached, and make no part of the line, they may be formed two deep, if it is found proper", and "With very few obvious alterations, these general rules take place when a company or battalion is permitted or ordered to form in two ranks only - and which, on the present low establishment of our battalions, may often be done for the purposes of exercise and movement on a more considerable front: it is also evident that they generally apply whether companies are strong or weak, and whether a greater or lesser number of them compose the battalion." [74] Elsewhere, it says two ranks are to be used, "when an extended and covered front is to be occupied". [75]

The habitual British use of two ranks, therefore, was not as a firepower multiplier. In the context of musketry the British infantry gained absolutely nothing from employing two ranks because the Rules and Regulations 1792 specified that infantry fired in three ranks anyway, either all three standing or with the first kneeling. [76] All available muskets were used regardless of the number of ranks employed, indeed, by forming in two ranks, thus extending the front, the number of rounds in the beaten zone was actually reduced in comparison with that produced by three ranks over a narrower frontage. All the evidence suggests that the use of two ranks by the British had absolutely nothing whatever to do with musketry.

The use of the third rank to extend the line in two ranks was not unique to the British. The third rank was also used for a number of detached roles, which in the case of the Austrians and Prussians included skirmishing. We have also seen that skirmishing was conducted in much the same manner by all nationalities. The popular impression that the French were significantly different in that context does not appear to be substantiated. That they did it with rather more flair or tactical flexibility seems probable but the evidence is inconsistent and varies depending upon the year and place. Any French advantage seems to gradually disappear from approximately 1809 onwards. On the other hand, there is little evidence to suggest that skirmishing by itself, by anyone, was a decisive factor.

Numerous modern accounts of battles and campaigns are written with a very broad nib, and it is rare to find one that investigates what soldiering entailed in the early 19th Century. The notion that the content of 18th and 19th Century drill regulations was mere theory seems to me to be just nonsense. Soldiers can only fight in accordance with the battle-drills they have been taught.

Of course the Napoleonic soldier learned his basic drill on the parade ground, where else would it have been done? That does not mean that it had no relevance to combat. On the contrary, although the regulations do contain some ceremonial, the larger part of the drill they described was intended for battle. It is impossible, in my view, to understand how battles were fought, without some understanding of the battle-drills used by the armies in question. "When we come down to it, the Reglements are the most solid and most authoritative deposits of our knowledge of military affairs - if not of its higher regions, then of its broad and essential bases." [77]

It seems to me that most military historical studies are written by authors who are not really concerned with the minutiae of the "broad and essential bases" of military affairs, merely its "higher regions". This is fair enough. However, very generalised attempts are frequently made, usually in the space of a few introductory paragraphs, to explain the differences in the system, tactical doctrine and abilities of one army or another. These often present a partial view, almost always French or British, repeating without question the myths and legends of the battle tactics of Napoleon and his enemies.

The trouble is that almost all the material on the other side of the coin is comparatively inaccessible, largely written in one kind of German or another and simply not available to most British readers, even if they do have some of the language. On the whole, it is understandable why it is not widely read.

However, over the past twenty years or so, parts of this material has appeared in numerous magazines, such as The Courier, Empires, Eagles and Lions and, indeed, First Empire. In addition, the occasional book has also dealt with the "broad and essential bases". The re-printing of Rothenberg's, Archduke Charles, which has been around for nearly twenty years, really leaves no excuse for the apparent absence of a basic understanding of how the Austrian army went about its business, set about reforms to meet the French threat, and the political and social changes that made such reforms possible. Paret's Yorck and Glover's Peninsular Preparation do the same thing for the Prussian and British armies.

My thanks are due to two friends for their help in completing this article. First to Dave Hollins for material from Gallina and elsewhere, without which the section on Austria would have been significantly less authoritative, but especially for access to his translation of Krieg 1809, which was an embarrassment of riches where examples of tactical practice were concerned. Similarly, thanks are also due to Peter Hofschröer for general comments and provision of additional collateral material, particularly on the 1806 campaign from Jany, previously reproduced in The Courier.

More Skirmishing

Footnotes[68] Taktische Grundsätze und Anweisung zu militärischen Evolutionen. Dundas's Assimilation of Cavalry and Infantry Tactics. The United Service Journal and Naval and Military Magazine, Part III. London, 1832. p11.

|