Meanwhile the main event at Cape

Gloucester had gotten under way. Elements of

the 1st Marine Division scheduled for the main

assault landings east of Cape Gloucester

conducted final rehearsals at Cape Sudest on 21

December. (This section is based on Craven and Cate,

The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, PP. 337-45;

Hough and Crown, The Campaign on New Britain;

Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, PP. 378-89;

Office of the Chief Engineer, GHQ AFPAC, Engineers

of the Southwest Pacific: 1941-1945, VI, Airfield and

Base Development (Washington, 1951), 192-95;

ALAmo Force Rpt, DEXTERITY Opn; 8th Area

Army Operations, Japanese Monogr No. 110 (OCMH),

pp. 119-22; 17th Division Operations in Western New

Britain, Japanese Monogr No. III (OCMH), pp. 14-21)

Meanwhile the main event at Cape

Gloucester had gotten under way. Elements of

the 1st Marine Division scheduled for the main

assault landings east of Cape Gloucester

conducted final rehearsals at Cape Sudest on 21

December. (This section is based on Craven and Cate,

The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, PP. 337-45;

Hough and Crown, The Campaign on New Britain;

Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, PP. 378-89;

Office of the Chief Engineer, GHQ AFPAC, Engineers

of the Southwest Pacific: 1941-1945, VI, Airfield and

Base Development (Washington, 1951), 192-95;

ALAmo Force Rpt, DEXTERITY Opn; 8th Area

Army Operations, Japanese Monogr No. 110 (OCMH),

pp. 119-22; 17th Division Operations in Western New

Britain, Japanese Monogr No. III (OCMH), pp. 14-21)

The heavily reinforced 7th Marines boarded ship at Oro Bay three days later and departed at 0600 on Christmas morning. En route ships carrying the reinforced 1st Marines (less one battalion landing team) from Cape Cretin joined up. The convoy then made its way peacefully through Vitiaz Strait, sailed between Rooke and Sakar Islands, and approached Cape Gloucester. The 2d Battalion Landing Team, 1st Marines, embarked at Cape Cretin and steamed through Dampier Strait for Tauali. (For Cape Gloucester Task Force 76 consisted of the flagship Conyngham, lo APD's, 16 LCI's, 12 destroyers, 3 minesweepers, and 24 LST's; 14 LCM's, 12 LCT's, and 2 rocket DUKW's went to Tauali. In reserve were the Westralia and Carter Hall. Detachments of the 2d Engineer Special Brigade-181 men, 33 landing craft, and 2 rocket DUKW's-were attached to the 1st Marine Division.)

Admiral Crutchley's Task Force 74--the American cruisers Phoenix and Nashville, HMAS Australia and HMAS Shropshire, and eight destroyers--escorted Task Force 76 while PT boats patrolled the northern and western entrances to the straits.

The Landings

EARLY MORNING BOMBARDMENT of landing beaches east of Cape Gloucester, 26 December 1943.

EARLY MORNING BOMBARDMENT of landing beaches east of Cape Gloucester, 26 December 1943.

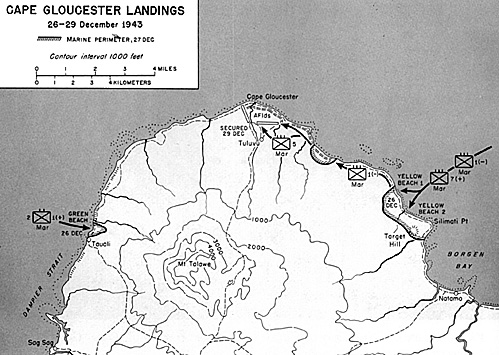

In the dim light of 0600 on 26 December Crutchley's ships opened their supporting bombardment on the landing beaches east of Cape Gloucester, a bombardment that continued for ninety minutes. Two new LCI's equipped with 4.5-inch rockets took station on the flanks as guide and fire support craft. After threading their way through -a difficult channel, APD's, in the lead, lowered landing craft full of troops while behind them LCI's and LST's awaited their turns at the beaches. (Map 18)

The 1st Air Task Force of the Fifth Air Force had prepared extensive plans for all-day air cover and support that involved a total of five fighter squadrons and fourteen attack, medium, and heavy bomber squadrons. The first support bombers arrived from Dobodura about 0700 and B-24's, B-25's, and A-20'S bombed and strafed the beaches and the airdrome. B-25's dropped smoke bombs on Target Hill, the 450-foot ridge just west of Silimati Point that gave clear observation of the beaches and airfields. A-20's strafed the landing beaches until the leading wave of landing craft was five hundred yards from shore. At that time the naval gunfire was moved inland and to the flanks.

An errant breeze blew so much smoke from Target Hill that some of the leading waves of landing craft carrying the 7th Marines could not easily identify the beaches. There was no opposition at the proper beaches, where most of two battalions of the 7th landed, but a detachment which wandered three hundred yards too far west. had a brisk fire fight on shore.

7TH MARINES LANDING ON NARROW BEACH, Cape Gloucester, 26 December 1943.

7TH MARINES LANDING ON NARROW BEACH, Cape Gloucester, 26 December 1943.

The 7th Marines found that the landing beaches were good but very shallow. And as the assault waves crossed the beaches they were brought up sharply by jungle so dense they had to start hacking to get inland. Immediately behind the beach was a narrow shelf of relatively dry ground. Behind the shelf was a swamp which made anything like rapid movement or maneuver completely impossible. Men floundered through the mud, slipping into sinkholes up to their waists and even their armpits. And in the swamp giant trees, rotted by water and weakened by bombs and shells, toppled over easily. The first marine fatality on Cape Gloucester was caused by a falling tree.

The narrow beach and the swampy jungle behind it caused a good deal of congestion, especially when the LST's began discharging their cargo. As expected, Japanese planes from Rabaul attacked the ships and the beach during the day, although their first attacks were directed against Arawe in the belief that the convoy had been intended as reinforcement for Cunningham. They sank one destroyer, seriously damaged two more, and scored hits on two others, as well as on two LST's.

By the day's end the 7th Marines held the beachhead area. The artillery battalions of the 11th Marines had landed and emplaced their howitzers. The 1st Marines had come ashore, passed through the 7th, and begun the advance west toward the airdrome. The regiment first attempted to advance with battalions echeloned to the left rear, but the swamp forced movement in a long column with a narrow front along the coastal trail.

Also on 26 December the reinforced 2d Battalion, 1st Marines' landed successfully at Tauali and D Company, 592d Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, 2d Engineer Special Brigade, landed on Long Island to prepare a radar station there.

The first night ashore at Gloucester was miserable, and it was the first of many more that were just as bad. Drenching rains characteristic of the northwest monsoon poured down in torrents; more trees fell. The Japanese in the airdrome area, estimating that only 2,500 men had come ashore, counterattacked the 7th Marines, but they failed, as did a heterogeneous group that later struck at the Tauali positions.

Capture of the Airfield

The 1st Marines started westward alono, the coastal trail toward the cape and the airfield at 0730, 27 December. The swamp still forced the regiment to advance in column of battalions, with the rear battalion echeloned as much as possible to the left rear. Each battalion marched in column of companies and sent small patrols into the swamp to protect its flanks. General Sherman tanks of A Company, 1st Tank Battalion, supported.

By 1615, when it dug in for the night, the regiment had gained three miles, and had become aware of the existence of a large Japanese block about a thousand yards east of the airfield.

Next day the 1st made deliberate preparations before attacking the block. The absence of Japanese resistance the day before had led to the conclusion that the enemy was concentrating his forces inside the block. The 1st Marines waited during the morning for more tanks to make their way up the trail, which by now was a veritable morass, and for artillery and aircraft to shell and bomb the block. The infantry and the tanks moved to the attack about noon and shortly ran into the block. This position was a strong point which originally had faced the sea for defense of the beach but which served alternately as a trail block. It consisted of camouflaged bunkers with many antitank and 75-mm, weapons. There was scarcely room for tanks and infantry to maneuver, but by the end of the afternoon the 1st Marines had reduced the block.

General Rupertus had been asking for his reserve, the reinforced 5th Marines, which had remained under Krueger's control, and on the 28th Krueger released the regiment. Rupertus then decided to hold up the advance on the airfield until the 5th arrived. It came on 29 December, but confusion over orders caused part of the 5th to land just behind the 1st, the rest at the D-Day beaches. When the 5th had been reassembled the drive began again.

The 1st Marines continued the coastal advance and, because the swampland on the left had given way to jungle, the 5th was able to make a wide southwesterly sweep. There was almost no resistance. By the day's end most of the airdrome was in Allied hands and the major objective of the campaign had been achieved.

The Japanese Withdrawal

This phase of the operation had gone rapidly and at the cost of comparatively few casualties. But the absence of Japanese opposition made it clear that a large body of the enemy must be elsewhere in the vicinity. Thus in the first two weeks of 1944 the 7th Marines and the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, tinder Brig. Gen. Lemuel C. Shepherd, the assistant division commander, attacked southward to clear Borgen Bay. Here waged the bitterest fighting of the campaign as the 141st Infantry struggled to keep possession of the high ground.

Thereafter there was little combat. The marines patroled extensively in search of the enemy, who proved to be elusive. B Company, 1st Marines, landed on Rooke Island on 12 February but found it had been evacuated. Eventually elements of Rupertus' division advanced by shore-to-shore movements as far east as Talasea without encountering any large numbers of Japanese. (In April the 40th Division relieved the 1st Marine Division and the 112th Cavalry on New Britain.)

The enemy garrison at Cape Gloucester, especially Matsuda's command, had been in poor physical condition before the invasion. The incessant air attacks against barge Supply routes had forced it onto short rations, and malaria, dysentery, and fungus infections were rife.

The 17th Division commander, Lt. Gen. Yasushi Sakai, seems to have had little heart for a resolute defense, for he urued General Imamura to approve a retreat to the Willaurnez Pen Insula. Imamura at first refused, then assented in January. On 23 February he ordered Sakai's entire command -- 17th Division, 65th Brigade, 4th Shipping Group, and all attached units -- to retreat all the way back to Rabaul and help defend it.

Base Development

Repair of the Wrecked airdrome began in early January With the arrival of the 913th Engineer Aviation Battalion. The Work was complicated and slowed by jungle, rain, and swampy ground, and by nocturnal air raids that prevented night work for nearly two weeks. GHQ and the Fifth Air Force revised their requirements and directed construction of a 5,000-foot strip and a second, parallel strip 6,000 feet long. The 864th and 141st Engineer Aviation Battalions arrived later in January and turned to on the strips and on roads and airdrome installations.

By the end of the month 4,200 feet of the first airstrip had been covered With pierced steel matting, but it was 18 March before the strip was completed. By then Rabaul, Kavieng, and the Admiralties had been neutralized or captured and GHQ Was planning the first giant step of its advance to the PhilipPines, a step Which took it far beyond range of fighter planes based at Cape Gloucester. (See Smith, The Approach to the Philippines, Ch. II.)

The parallel 6,000-foot strip proved impossible to build and was never completed.

Cape Gloucester never became an important air base. It is clear that the Arawe and Cape Gloucester invasions were of less strategic importance than the other CARTWHEEL operations, and in the light of hindsight were probably not essential to the reduction of Rabaul or the approach to the Philippines. Yet they were neither completely fruitless nor excessively high in casualties. The 1st Marine Division scored a striking tactical success at the cost of jio killed, 1,083 wounded. And the Allied forces of the Southwest Pacific Area had, by means of these operations, broken out through the narrow straits.

More Crossing the Straits

- Plans and Preparations

The Japanese

Battle of Arawe

Operations: 16 December 1943-10 February 1944

Battle of Cape Gloucester

Battle of Saidor

Back to Table of Contents -- Operation Cartwheel

Back to World War Two: US Army List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com