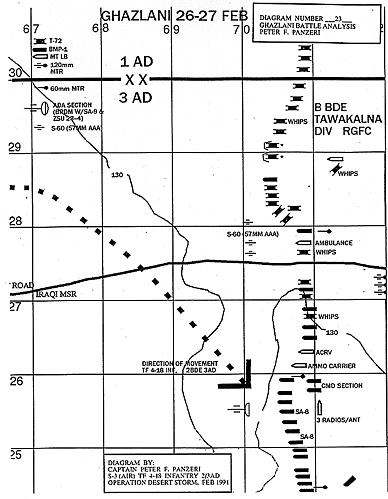

Battle of Ghazlani

February 27th, 1991

Tactical Situation

by Pete Panzeri

| |

The desert in southwest Iraq is generally flat. The ground surface is sand and gravel throughout with local concentrations of baseball to basketball sized rocks. There are some wadi (dry stream beds) networks and, at places, hill outcroppings dominate the surrounding terrain. (TF 4-18 OPORD 91-010)

A paved road runs from east to west through the Ghazlani battlefield. This was the Tawakalna Division's main supply route (MSR), and the B Brigade was deployed astride of this road. The road was the only recognizable terrain feature in the area for many miles, and as such, it was critically important for the Iraqis. They relied heavily on such roads to navigate their maneuver and logistical elements across the otherwise featureless desert. (ANNEX B (INTEL) TO 4-18 OPORD 91-010) At first glance, the size and composition of the opposing forces at Ghazlani appear evenly matched. Thirty of the Republican Guard's best T-72 tanks and thirty BMP-1 armored personnel carriers were defending against fourteen M-1A1 tanks and fifty one Bradley armored personnel carriers.

Task Force 4-18 was formed with one Armor company (TEAM WHISKEY) of fourteen M-1A1 tanks, three nfantry companies (A, B, and C) of fourteen M2A1 Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicles, a scout platoon of six Bradleys, a mortar platoon of six 4.2" mortar carriers, an engineer company (A Co. 23rd Eng.), two command post elements, a Combat Trains formation of over 35 resupply and support vehicles, and two air defense platoons. The task force was directly supported by a battery of six M-109 armored, self-propelled, 155mm artillery pieces. (TF 4-18 OPORD 91-010) Each infantry company had a headquarters section of two Bradleys and three platoons of thirty infantrymen riding in four Bradleys. The infantrymen carried M-16 rifles, several light machine guns, and the single shot AT-4, an 84mm anti-tank rocket launcher. Bravo Co. cross-attached (traded) Team Whiskey one infantry platoon for a platoon of tanks. This provided two combined arms teams with an armor and infantry combination (Teams Bravo and Whiskey) and two mechanized-infantry "pure" companies (Alpha and Charlie). (TF 4-18 OPORD 91-010) Bradley Infantry Frighting Vehicle The mainstay of combat power for the infantry platoons was the Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle. This armored vehicle gives the infantryman mobility on the battlefield, with speeds up to 45 mph, and protection from small arms and artillery fire. Each vehicle has a radio for voice communication with the platoon leader, company commander, or dismounted elements. The platoon leader can fight mounted in the turret of his Bradley, or he can dismount with his infantry platoon and still maintain command control with a back-pack radio. (Chadwick, p.38) The Bradley has an impressive arsenal of weapon systems. It has a 7.62 mm machine-gun with a 1,000 meter range. The main weapon is the 25mm chain gun that can deliver rapid fire (200 rounds per minute) at a pinpoint target 2,800 meters away. The gunner can select high explosive anti-personnel rounds or high velocity armored piercing rounds with the flick of a switch. The Bradley also carries a dual launcher for the TOW Missile. (TOW = Tube-launched Optically-tracked Wire-guided) The TOW is a guided missile that can penetrate any known armored vehicle at ranges up to 3,750 meters. (FMC Fact Sheet) In addition to rapid, devastating firepower, the Bradley has a thermal sight that enables the gunner and Bradley commander to see targets over 6,000 meters away, day or night. The thermal sight can also detect visual targets through dust and smoke, and can detect mines buried in the ground. (FMC Fact Sheet) BMP-1 The Soviet-built BMP-1, used by the Iraqis at Ghazlani, has a 7.62mm machine-gun, with speed and armor similar to the Bradley's. The BMP's main weapon system is a manually loaded 73mm cannon that can easily penetrate the Bradley's armor, but has a rate of fire of only 8 rounds per minute. The BMP-1 has one launcher for an AT-3 Sagger Anti-Tank Guided Missile (ATGM). The Sagger has a range of about 3,000 meters and will penetrate the Bradley, but not the frontal armor on the M-1A1 Tank. The Iraqi infantrymen carry comparable small arms to the US troops, but their hand-held anti-tank weapon, the RPG-7, is reloadable, with a range of about 500 meters. The night vision sight for the BMP-1 uses an infrared lamp. It is only effective up to 1,300 meters in ideal conditions and will not work in sand or dust storms. When the infrared lamp is in use, it is visible through a thermal sight, like a flashlight beacon in the dark. The M-1A1 Tank has sufficient frontal armor to deflect any of the Iraqi anti- tank weapon systems. It weighs 65 tons and travels across the desert at speeds up to 50 mph. The M1A1's greatest weakness, critical in desert warfare, is its high fuel consumption. It burns nearly four gallons a mile, and fuel consumption does not decrease while the tank is idling. (Armored Fist, p. 86) The M1A1's main gun is a 120mm smoothbore cannon that can fire an APFSDS round (Armor Piercing Fin Stabilized, Discarding Sabot), a depleted uranium dart, 18 inches long, through the front armor of any Iraqi tank at ranges well over 3,000 meters. With a sophisticated laser range-finder and thermal sight the M1A1 is arguably the best tank in the world. (Chadwick, p. 30) The Iraqi T-72 tank has insufficient armor to deflect a TOW missile or APFSDS. The T-72M1 version, encountered at Ghazlani, is up-armored to 400mm in places, but that is not enough. The fuel and ammunition are stored tightly together, causing a high percentage of hits to become catastrophic kills. It has a laser rangefinder but suffers from the same infrared sight weakness as the BMP-1. The T-72's 125mm main gun is fairly accurate, but only up to 1500 meters. (Chadwick, p. 32) Most of the T-72s captured at Ghazlani held 30 or more high explosive rounds and only a handful (4 or 5) of APFSDS anti-tank rounds. (Jones, p. 14) The most significant technological advantages at Ghazlani lay in the superiority of the thermal sights. The Iraqis were unable to see or engage targets out to such extreme ranges with their equipment. Other technological advantages include the unchallenged superiority in air power. The Iraqi movements were pin-pointed with exceptional accuracy. They were pounded from the air long before (during and after) they engaged the Coalition forces on the ground.

The hand-held Globat Positional System Unit, which helped allied forces navigate through the desert.

Satellite-directed navigational aids enabled the US forces to navigate in the desert without following roads or terrain features. This facilitated command control and allowed logistical support to easily locate and resupply forward units. Each of these technological advantages increased the compounded effect of the others. The technological edge created strategic, operational, and tactical advantages that the Iraqis could not hope to overcome. (Chadwick, p. 32)

Logistically, both forces at Ghazlani were well-supplied. Allied air interdiction had hampered Iraqi combat service and support efforts somewhat, but the Tawakalna Division was high on the resupply priority list. The Republican Guards were less than a night's drive from the city of Basrah. Nightly convoys kept combat elements from running low on essential items. (2/3AD AAR)

All of the Iraqi armored fighting vehicles inspected on the Ghazlani battlefield were fully uploaded with ammunition. Several re-supply caches were nearby. Water and food were plentiful also. The Iraqis had boxes of fresh tomatoes in most of the infantry squad fighting positions.

Some of the T-72M1 tanks were low or dry on fuel, which would indicate a need for tactical refueling but not necessarily a critical logistical shortage. The US tanks from 2nd Brigade, 3rd Armored Division, were also very low on fuel at Ghazlani. The brigade's lead tank battalion, Task Force 4-8 Cavalry, had to disengage during the battle and conduct emergency refuel operations before continuing operations.

The entire 3rd Armored Division's fuel status reached "RED" (less than 50% of basic requirement) on the afternoon of February 26. As the armored formations moved deeper into Iraq, 100 miles at this point, fuel was critically short. The turn around time for fuel convoys back to Saudi Arabia grew longer by the day. The VIIth Corps was stretching the limits of its logistical support. Task Force 4-18 did not suffer as severely because the BFVs did not burn as much fuel as the M1A1. TF 4-18 also carried two complete ammunition re-supply loads with their combat trains. Neither side at Ghazlani would run out of bullets to shoot at each other. (Leonard, p. 3)

Command and Control

Tactical command and control assets were adequate on both sides. The Iraqi operational communications were seriously degraded by aerial interdiction and US signal deception and jamming. However, within the Tawakalna B Brigade facing Task Force 4-18, communication was still effective. (2/3AD AAR)

US Command and control assets were extensive. Every combat vehicle had a radio. All leaders were able to talk over a secure (scrambled) voice radio net. This security allowed leaders to freely give grid coordinate locations and sensitive information without fear of enemy interception.

The main command post (CP) for Task Force 4-18 was the Tactical Operations Center (TOC). The TOC had four M577 armored command vehicles, each with additional headquarters staff and communication equipment. One M577 was used for each cell of the TOC. (S-2 Intelligence, the Fire Support Element, The Engineer Command Post, and the S-3 Operations Cell) Also collocated with the TOC were the Air Defense Officer and the alternate CP for the Air Liaison Officer (ALO). The TOC was led by the battalion executive officer, who had his own BFV available.

The battalion commander led from his Bradley, which was part of the Tactical Command Post (TAC). The TAC included the commander's and S-3's BFVs and two M113 armored personnel carriers. One M113 was outfitted with aircraft compatible radios for the ALO, and the other carried the Engineer Company Commander. The command and control assets were echeloned so that the loss of any leaders would not eliminate the units ability to communicate and function.

US aerial reconnaissance and intelligence capabilities enabled the Americans to know where the Iraqis were, and by intercepting radio messages, what they were planning to do. Captured enemy prisoners of war (EPWs), including many of the junior officers, were very informative when interrogated. TF 4-18 had an EPW interrogation team attached for immediate processing of information. A misreading of this extensive intelligence led to TF 4-18 stumbling right into the Iraqi reverse-slope defense. (TF 4-18 AAR)

Iraqis Not Completely Blind

The Iraqis were not completely blind on a tactical level. They had placed numerous observation posts, forward security elements, and scouting elements to their front. The US had a marked advantage, but it failed to protect them from the surprise, close range engagement at Ghazlani. (TF 4-18 AAR)

Tactical training and doctrine of the two opposing forces were evenly matched. The US forces were extensively trained with their equipment and the AirLand Battle Doctrine of combined arms warfare. Detailed training exercises were conducted in the Saudi Desert to hone their skills. Task Force 4-18 conducted several training operations dubbed THERMALEXs. During the exercises all fighting vehicle crews were required to pass a test, identifying several dozen different types of vehicles through thermal sights. This identification training resulted in no friendly fire incidents within the Task Force.

The Tawakalna Division trained and fought according to Soviet doctrine modified by their experiences in the Iran-Iraq War. They were more inclined to fight a war of attrition than of maneuver. In 1987 the Iranians repeatedly assaulted the heavily fortified city of Basrah, but never captured it. The battle for Basrah lasted almost a year and rivals that of Verdun in WWI. The Iraqis inflicted 3-to-1 casualties on their attackers and became experts at defensive, attrition warfare. Their most successful tactic against the Iranians was to conduct limited attacks and then defeat counterattacks with an elaborate defense of entrenched positions, concentrated artillery and massed armor formations. (Antal, p. 66)

The Republican Guards divisions had the highest concentration of trained veteran soldiers in Saddam Hussein's army. They were in much better condition than the neglected line divisions in southern Kuwait. Their morale was high at the outset of the campaign, but after six weeks of witnessing Coalition air supremacy from the receiving end, some were waning in enthusiasm. (Jupa, p. 44)

Inaccurate Post-Battle Pronouncements

The Coalition's tremendous victory has led to some very inaccurate post-battle pronouncements. One of the most interesting is that the Iraqis did not fight. While the conscripts and front line infantry divisions did tend to quickly cave in, the armored and mechanized formations echeloned in reserve fought and, in many cases, fought very hard. Nowhere was this more true than with units of the Republican Guards. (Chadwick, p. 11)

Once convinced that their situation was hopeless, and once morale broke, even the Republican Guards soldiers surrendered. The Coalition's Psychological Operations (PSYOPS) campaign was evident. Nearly every Iraqi prisoner surrendered holding a propaganda leaflet promising safe conduct and condemning Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait. These soldiers were not fighting a vicious religious war as they had against Iran. For the most part they did NOT continue to fight in small groups when they were cut off from their command and control elements. (Fialca, p. 3)

The Iraqi battlefield leaders at Ghazlani were combat veterans. They had made no error in establishing an effective reverse slope defense, with ample armor reserve, and artillery support. The leaders were positioned forward where they could most influence their troops. They may have been caught by surprise when the US formations attacked at night, but the stage had been set for them long before the first shot was fired. For the Iraqi battlefield leaders, it was a no win scenario. (Fialca, p. 4)

The battlefield leadership in Task Force 4-18 was equally competent despite combat inexperience. Lieutenant Colonel Fulcher, Major Fitch, and each of the company commanders were well forward during the 16 hour fight, many of them directly engaging the enemy from their armored vehicles. Their presence during the fight and continuous cross talk over the radio kept the Task Force alert and combat effective throughout the night.

More Ghazlani

Strategic and Operation Setting Tactical Situation Engagement at Ghazlani Signifiance of the Action, Sources Day Maps Large (very slow: 280K) Day Maps Jumbo (extrememly slow: 509K) Back to Veteran Campaigner List of Issues Back to Master Magazine List © Copyright 1997 by Pete Panzeri. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |

At Ghazlani the contour appears flat, but it is not. There are several very subtle rises and drops in elevation until the terrain rises significantly about 10 kilometers east of the battlefield. These subtle rises and ridge lines are very deceiving when viewed from the west. The gentle ridge line at Ghazlani is high enough to conceal armored vehicles but low and gradual enough to be overlooked as a terrain feature. (TF 4-18 AAR)

At Ghazlani the contour appears flat, but it is not. There are several very subtle rises and drops in elevation until the terrain rises significantly about 10 kilometers east of the battlefield. These subtle rises and ridge lines are very deceiving when viewed from the west. The gentle ridge line at Ghazlani is high enough to conceal armored vehicles but low and gradual enough to be overlooked as a terrain feature. (TF 4-18 AAR)

Both sides were supported by engineers, air defense units, and ample artillery support. The Iraqis even appear to have had an advantage in tanks and dug in positions. That advantage only applies if one is counting guns and nothing else. (TF 4-18 AAR)

Both sides were supported by engineers, air defense units, and ample artillery support. The Iraqis even appear to have had an advantage in tanks and dug in positions. That advantage only applies if one is counting guns and nothing else. (TF 4-18 AAR)