Battle of Ghazlani

February 27th, 1991

Strategic and Operation Setting

by Pete Panzeri

| |

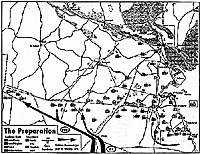

Large Preparation Map (slow: 124K) The Emir of Kuwait, Sheik Jaber al-Almad al-Sabah, barely escaped in a helicopter as his palace was assaulted by Iraqi tanks. The Iraqi dictator, President Saddam Hussein, declared to the world that his forces were supporting a popular revolution of the Kuwaiti people. When no Kuwaiti support for the uprising materialized, Saddam Hussein annexed Kuwait. He claimed that Kuwait had been an Iraqi province since ancient times. News coverage from Baghdad, the Iraqi capital, indicated that the Iraqi people were enthusiastically supporting their charismatic leader, Saddam Hussein. (David p. 35) The international reaction to Saddam's annexation was one of shock and surprise. Prior to the invasion, the United States' intelligence network had monitored the Iraqi troop build up on the border, but it was dismissed as only a show of force. The US ambassador to Iraq, April Galaspie, told Saddam Hussein that his confrontation with Kuwait was, "an issue for the Arabs to solve among themselves. . . the US has no position opinion on inter-Arab disputes such as your border dispute with Kuwait." (Eldridge p. 12) Once Kuwait had fallen and the oil resources of the Saudi Arabian Peninsula lay threatened, the US took an official position on the issue. The Gulf War had begun. War There have been countless third-world border wars, invasions, and toppled governments since the end of WW II. Historically, the US has refrained from military involvement in these conflicts. However, control of the Persian Gulf's oil resources is not just a control of wealth, but more-so control of power. To allow this power to remain in the hands of a ruthless and unpredictable dictator was declared unacceptable by the United States Government. (Beyer p.26) U.S. President George Bush condemned the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and campaigned in the United Nations (UN) for international support. When Iraqi forces began to deploy on the Saudi Arabian border, the Saudi leaders allowed U.S. forces to deploy there. On the 8th of August, paratroopers from the US 82nd Airborne Division and 48 US Air Force F-15 Fighter Jets landed in Saudi Arabia. Thus began Operation Desert Shield, a military buildup that would eventually total over 540,000 US troops, 2,000 tanks, 2,200 armored personnel carriers, 1,700 helicopters, 1,800 airplanes, 6 aircraft carriers, and 100 warships. The US forces formed roughly two thirds of the international coalition sent to stop Saddam Hussein and eventually oust his Army from Kuwait (David p. 64) From August to November of 1990, diplomatic pressure and economic sanctions emanated from the the United Nations and isolated Iraq. The buildup of Coalition forces in Saudi Arabia, Operation Desert Shield, proved to be a military mobilization of unprecedented proportion and speed. On November 8, 1990, the US VIIth Corps, already deployed in Europe, was given the order to move to Saudi Arabia. The United Nations forces in South West Asia were no longer in a defensive posture. The VIIth Corps added sufficient combat power to coalition ground forces to allow offensive ground operations against Iraq. (Watson, p. 40) This strategic military setting held three key points that directly affected the tactical battle at Ghazlani. First, an extreme emphasis on caution was expressed down to the lowest tactical units. Saddam Hussein's claim of "sacrificing a hundred thousand Iraqi lives to make the Allies pay for Kuwait" was not a hollow threat. Sufficient combat power was to be massed, with every possible advantage stacked, before engaging the enemy. Minimizing the loss of American lives was written into the commander's intent of the Operation Order: "Commander's intent: Never close within direct fire range of the enemy. Use Artillery, Close Air Support, and the advantage of our superior direct fire weapons systems to defeat the enemy." (2BDE/3AD OPERATION ORDER 91-1) Techical Superiority The technical superiority of the US weapons systems would be the mainstay of all operations. Bold tactical moves would take a back seat to cautious, methodical destruction of enemy forces by superior and overwhelming combat power. Iranian victories over Iraq during their protracted war were due both to the professionalism of Iranian regular army leadership and a total disregard for casualties. (Antal p. 66) There would be no such disregard in this war. The strategic concern for casualty minimization was evident and overbearing in even the smallest of operations. Second, the six month delay from the August, 1990, initial deployment of U.S. armed forces until the 24 February, 1992, commencement of the ground campaign (G-DAY) allowed the rapidly deployed VIIth Corps enough time to prepare. Time was essential for logistical pre-positioning, desert training and adaptation, gunnery practice after deployment, and detailed mission planning prior to entering combat operations. Unlike the outbreak of the Korean war, when US forces were hurriedly committed piecemeal and unprepared, the US VIIth Corps enjoyed the military luxury of a strategic political delay. (Kindsvatter, p. 17) Third, Saddam Hussein's prolonged deployment and continued expansion of his armed forces after the Iran-Iraq War thinned the ranks of his army and, most significantly, the Republican Guards Forces Corps. Their "elite combat veteran" status was diluted as the units became inundated with new recruits and conscripts. This lowered the ratio of experienced small unit leaders essential for military cohesion. (Eshel, p. 251) Hopeless Tactical Situation After six weeks of aerial bombardment, and many months of deployment in the desert, the Iraqi Republican Guards divisions were still willing and able to conduct combat operations. However, the Republican Guards were about to fight in a hopeless tactical situation, against an army with overwhelming technological superiority. When faced with these odds, fighting morale and small unit leadership becomes critical to continuing a fight. (Jupa, p. 44) Hoping that all of his soldiers would fight fanatically despite enormous disadvantages, Saddam Hussein called for an Islamic Jihad, or Holy War. Saddam's strategic propaganda failed to convince all of his soldiers to die for Allah. In the end, this strategic ploy contributed to the disintegration of his most elite forces' fighting morale. (Jupa, p. 46) The operational setting that resulted in the battle of Ghazlani began with a five and a half week week air campaign that devastated the Iraqi military and ended with a "100 Hour Ground War" that has few historical comparisons. The tactical battle at Ghazlani exemplifies the culmination of a modern combined arms campaign. The battle also demonstrates the effect and value of maneuver warfare as experienced in Operation Desert Storm. Planning for the liberation of Kuwait began long before the Allied Coalition forces were assembled. The final approved plan was waiting for the 3rd Armored Division Staff when they "stepped off the boat." (Hamer p. 5) The offensive was to be executed in two phases: a massive, sustained aerial bombardment followed by a brief, shattering, and violent ground offensive intended to eliminate Iraqi forces deployed in the Kuwaiti Theater of Operations (KTO). (Chadwick, p.76) Saddam Hussein's army deployment shows that he expected a frontal assault on Kuwait. He massed the majority of his Regular Army units in Kuwait. He placed his least reliable line infantry divisions along the border, defending an elaborate obstacle belt and bunker complex. This defense in depth, strengthened with concentrated artillery batteries, became known as "The Saddam Line." Directly behind it were several Regular Tank divisions forming a mobile reserve. The mission of the armored formations was to counterattack any Coalition penetrations or cut off any flanking attempts. The Republican Guard Forces Corps formed a strategic reserve in southern Iraq. These five divisions were available to counter a Coalition ground threat from the sea, through Kuwait, or from the west. (David, p. 76) The Coalition plan for liberating Kuwait, the ground offensive of Operation Desert Storm, was based on a flanking maneuver. The offensive was not aimed at attacking Kuwait from the west, but to fully envelop the entire country, cutting off all of the Iraqi troops deployed there. The main objective of this attack was not terrain oriented, but targeted the strongest concentration of Iraq's combat power: The Republican Guards Forces Corps. Engaging the Republican Guards was determined to be the decisive point and the war's main effort was to be focused on this decisive point. (2/3AD OPLAN 91-1) The offensive was designed to exploit the coalition's superior mobility and the enemy's vulnerability to air attack. Two Saudi-led Coalition Corps and the US 1st Marine Expeditionary Force would attack directly north into Kuwait. This would be a feint, with enough combat power to draw Iraqi reserves further down into the fight. This deception plan was intensified with the threat of a US Marine Corps amphibious invasion along the Kuwaiti coastline. (David, p. 76) Deception Plan To support the deception plan, all coalition forces were kept south of Kuwait, east of the Wadi al Batin. Just before G-DAY, the XVIIIth Airborne Corps (US 82d and 101st Airborne divisions, 24th Mechanized Infantry Division, and French 6th Light Armored Division), led by Lieutenant General Gary Luck, was to move several hundred kilometers to the west. The Airborne Corps' mission was to drive deep into the heart of Iraqi territory and seize key road junctions in the Euphrates River valley. This would effectively isolate the Iraqis, including the Republican Guards, from their lines of supply. The Iraqi Army would then have to surrender or fight its way out. (2/3AD OPLAN 91-1) Any attempt by the Republican Guards Forces to react or escape would force them to engage the US VIIth Corps. The US VIIth Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Fred Franks, was composed of the British 1st Armored Division (1AD-UK), the US 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment (2ACR), 1st Infantry Division (1ID), the 1st Armored Division (1AD), and the 3rd Armored Division (3AD). The VIIth Corps assumed the mission of focusing the main effort of Operation Desert Storm on the decisive point: engaging and destroying the Republican Guards. . . or as Saddam Hussein put it: "The mother of all battles." (2/3AD OPLAN 91-1) When this plan was originally envisioned, the VIIth Corps was still in Europe and had to move to the war zone in time to take part. The deployment operation was the first of many first time milestones for the 3rd Armored Division and its 2nd Brigade. These milestones began with an overseas deployment notice and ended up at a place called Ghazlani, in southern Iraq. (Hamer, p. 6) Deployment Plan The deployment plan for the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Armored Division (2BDE, 3AD), was ambitious to say the least. The goal, set after the 8 November 1990 notification, was to have all personnel and equipment in Saudi Arabia and combat ready prior to the January 15, 1991. Hostilities were expected to resume soon after the 15 January deadline set by UN Resolution number 678. The 2BDE's equipment and vehicles (over 800) were moved by rail and barge from their garrison in Gelnhausen, Germany, to the ports of Antwerp and Rotterdam. (2/3AD AAR) Fourteen ships and 34 sea/land containers were required to deploy the "Iron Brigade" to Saudi Arabia. Most of the 2nd Brigade soldiers arrived, by chartered commercial aircraft, on December 27, 1990. (It was two months to the day before their climactic battle at Ghazlani.) The soldiers immediately began to off-load their equipment from ships as they arrived at the Saudi port of Dammam. (2/3AD AAR) Operation Orders for the liberation of Kuwait were first delivered in early January, while the "Iron Brigade" was at the Saudi port of Dammam. The US VIIth Corps was officially identified as the theater "main effort." The VIIth Corps was tasked with an operational flanking maneuver, moving through the Iraqi Desert west of Kuwait. The mission statement was simple but not specific: "On order, VII Corps attacks to penetrate Iraqi defenses and destroy the Republican Guards Forces in Zone. . ." (3AD OPLAN 91-1) Spearhead The US 3rd Armored "Spearhead" Division along with the US 1st Armored Division were to be the main effort of the VIIth Corps' attack into Iraq. The objective of these two armored divisions, the highest concentration of combat power in the theater, was to move rapidly and strike at the heart of the Iraqi military might: the Republican Guards Forces Corps. (3AD OPLAN 91-1) The 3rd Armored Division mission mirrored that of the VIIth Corps: "On order, 3AD moves to, secures, and defends assigned Tactical Assembly Area and Forward Assembly Area. Attacks in zone to destroy the Republican Guards Forces and defends northern Kuwait.. . ." (3AD OPLAN 91-1) The 3rd Armored "Spearhead" Division plan, named Operation Desert Spear, was a six phase operation. The Division Commander, Major General Paul E. Funk, ordered the 2nd "Iron Brigade" to lead the Division advance along Axis Liberty. The 3AD would occupy a position known as Objective Collins to fix and destroy the the Republican Guard Forces Command. (3AD OPLAN 91-1) Phase One was the movement of personnel and equipment to a Tactical Assembly Area (TAA) code named Henry. TAA Henry was 130 kilometers south of the Saudi-Iraqi border east of the Wadi al Batin. All of the Coalition forces were assembled east of the Wadi, and no movement was allowed to the west. This was part of the deception plan aimed at convincing Iraqi intelligence that the main attack would come along the Gulf Coast into Kuwait from the south. (3AD OPLAN 91-1) Phase Two of operation Desert Spear was to commence just two days prior to launching the ground offensive. The entire 1st and 3rd Armored divisions would move 160 kilometers west and occupy Forward Assembly Area Butts, 30 kilometers south of the Saudi-Iraqi border. This was to be the last point of preparation prior to combat. (3AD OPLAN 91-1) Phase Three was the passage through the obstacle belt along the Iraqi border. Engineers attached to the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment, (the VIIth Corps' screening element) were to cut several dozen lanes in the double-row 8-foot berms along the border. Each element in 3AD was assigned a lane in a meticulous passage plan. (3AD OPLAN 91-1) The fourth phase of Operation Desert Spear called for the Spearhead Division to advance along Axis Liberty to Objective Collins. Collins was nothing more than an empty spot in the desert, north-west of Kuwait. It was of no significant tactical value, except that this was where the G-2 (intelligence) expected 3AD to meet the Republican Guards if they came out of their defensive positions. (3AD OPLAN 91-1) Just before the campaign began, one of the G-2 experts noted that the Objective Collins area was an Iraqi Army training area. This soon-to-be desert battlefield was the Iraqi equivalent of the US Army's National Training Center at Fort Irwin, California. It was going to be an Iraqi "home game." If, at Collins, the Republican Guards refused to give battle and counterattack out from the northern Kuwait area, the next course of action would be determined contingent upon Iraqi deployment. (3AD OPLAN 91-1) The plan's fifth phase entailed the Spearhead Division's part in destroying the Republican Guards Forces Corps. This phase was not scheduled to begin until all of 3rd Armored Division's trailing elements, logistics and combat support, reached Objective Collins. (3AD OPLAN 91-1) Four contingency plans (CONPLANs) were drawn up to meet with the scenarios envisioned for engaging the Republican Guards Forces Corps.

HONOR MOVEMENT ALONG AXIS LIBERTY INITIATES 3AD ATTACK. TANNENBURG ATTACK ENEMY IN DEFENSIVE POSITIONS AFTER FINDING EXPOSED FLANK OR REAR. AUSTERLITZ 3AD ATTACKS WITH ALL THREE BRIGADES FORWARD AND ON LINE ARDENNES 3AD BLOCKS AN ENEMY COUNTER ATTACK (3AD OPLAN 91-1) The sixth and final phase of Operation Desert Spear, and Desert Storm, was to be the defense of northern Kuwait. The 3rd Armored Division would withdraw out of Iraq and establish defensive positions to block any further attacks by Iraqi forces. (3AD OPLAN 91-1) The over-all plan called for an enormous operation of great complexity. Operation Desert Storm is rivaled in sheer size only by Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy in June, 1944. The operation realizes the post Vietnam theories of war proven effective in Grenada and Panama: massive force delivered by troops trained in the use of advanced technology weapons can overwhelm the enemy while limiting friendly casualties. (Mathews p.12) The doctrine evoking this updated approach to warfare is called AirLand Battle. US Army doctrine experts insist that air and land be joined into one word to emphasize the critical importance of aerial attack-and-maneuver to the war-fighting scheme. General Norman Schwartzkopf, the US Theater Commander, would employ the tenets of AirLand Battle (Agility, Initiative, Depth and Synchronization) trusting air power to ensure the security of his flanks and his armored thrust forward. (Armored Fist, p.176) Leadership At the very top of the Coalition leadership in the KTO was General Norman Schwarzkopf, head of the US Army Central Command. As a West Point Graduate, Infantry Officer, and highly decorated veteran of the Vietnam War, Schwarzkopf displayed the personality and charismatic character needed to lead such a multinational coalition. His deputy commander, General Calvin Waller, assumed command of the 3rd Army during the ground offensive, replacing Lieutenant General John Yeosock, who was ill. (Chadwick, p. 76) Lieutenant General Frederick M. Franks commanded the US VIIth Corps during Operation Desert Storm. Lieutenant General Franks had held the job for over a year, in Europe, before the deployment to Saudi Arabia. This General with a wooden leg assumed command of the VIIth Corps after a successful tour as commander of the 1st Armored Division. (Desert Jayhawk, p. 1) The Commanding General for 3rd Armored Division was Major General Paul E. Funk. During 1990 he and his Spearhead Division spent 150 days in the field, training at various places in Germany. He set demanding standards for gunnery and maneuver training. (Desert Jayhawk, p. 21) The 2nd Brigade, commanded by Colonel Robert Higgins, had just completed six straight weeks as the Opposing Force (OPFOR) at the Combat Maneuver Training Center at Hohenfels, Germany. This extended training period gave commanders at every level the experience needed to coordinate operations as part of a large brigade and division team. (Jones, p. 6) Colonel Higgins was hated and feared by many of the Iron Brigade officers. He was a career soldier with over 20 years of service. He was notorious for bombarding his subordinates with an intense barrage of questions and queries during every briefing, routinely taking several hours to complete a 30 minute agenda. Wrinkled and wiry, he looked much older than most of his contemporaries. Higgins' appearance and vicious temperament earned him the nick-name Freddy, after the terrifying character Freddy Kruger in the horror movie Nightmare on Elm Street. (Jones, p. 16) The commander for Task Force 4-18 Infantry, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Fulcher, was also a career soldier with over 20 years in the Army. An infantryman, ROTC Graduate, and one of the few black combat-arms battalion commanders in the US Army, Fulcher was a unique leader. He was well educated, and knowledgeable, but his patterns of speech were less than polished, and filled with vernacular clichés. He could be stern and unbending in his policies, but he often tolerated back talk from his company commanders during meetings or, much worse, over the battalion radio net. He was well versed in tactics and doctrine, but he relied extensively on his gifted Operations Officer (S-3) Major James Fitch, to orchestrate the battalion's tactical maneuver. The Fulcher-Fitch team was the true strength of Task Force 4-18's leadership. Fitch's professional demeanor, near photographic memory, and rapport with the fiery 2nd Brigade commander were the perfect complement to Fulcher's relaxed disposition. (personal observation) None of the principal US commanders at Ghazlani had seen combat before. All were career soldiers in a standing professional army. All of their previous training and professional development was intended to prepare them for battle. Their ability to lead, make decisions, and keep calm under fire, was yet to be proven. Iraqi Leadership The Iraqi Army was led by Saddam Hussein, supreme commander of all Iraqi forces. He personally planned the invasion of Kuwait and several ill-fated spoiling attacks near Kafji, Saudi Arabia. He micro-managed the deployment of troops in the Kuwaiti Theater of Operations, much to his Generals' objections. His despotic rule required tight control over every department. His brother-in-law, General Khairallah, led the Republican Guard in a series of smashing victories during the Iran-Iraq War. Khairallah was mysteriously killed, along with several other talented Iraqi generals, after he became too popular for his own good. (Chadwick, p. 77) Many of the higher level Iraqi generals, including Saddam's chief of staff, and the Republican Guards commander, were sacked and replaced by political yes-men after the invasion of Kuwait. The tactical commanders in the Republican Guard Tawakalna Division escaped the wrath, but they no doubt were intimidated to see the plight of their superiors. (Chadwick, p. 77) The Iraqi Task Force commander captured at Ghazlani, Major Saddam Rashid was from the B Brigade, Tawakalna Division. Interrogation reports show that he was an veteran of the war with Iran, and possibly an aristocrat, loyal to the ruling Baath political party. He was aloof and arrogant when captured. He was unruly, and refused to march away with the enlisted Iraqi prisoners. Some of his soldiers displayed contempt for him after capture. (Leonard, p. 5) The Iraqi high command was critically short on competent professional soldiers The result placed the capable and experienced lower level commanders in extreme jeopardy. This was due to the military leadership of Staff-Marshal Saddam Hussein, a man with no prior military service, as an officer or enlisted man. (Chadwick, p. 77) General Norman Schwarzkopf commented on his opponent's leadership: "He is neither a strategist. . . nor is he a tactician, nor is he a general, nor is he a soldier. Other than that, he's a great military man." (David, p. 120) More Ghazlani

Strategic and Operation Setting Tactical Situation Engagement at Ghazlani Signifiance of the Action, Sources Day Maps Large (very slow: 280K) Day Maps Jumbo (extrememly slow: 509K) Back to Veteran Campaigner List of Issues Back to Master Magazine List © Copyright 1997 by Pete Panzeri. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |

In the 2:00 a.m. darkness of August 2, 1990, the Army of Iraq invaded its tiny oil-rich neighbor, Kuwait. The attack, spearheaded by tanks and troops of the elite Republican Guards Forces Corps, encountered only slight resistance. Within twenty-four hours, the capital, Kuwait City, was completely under Iraqi control. Only a few scattered remnants of the Kuwaiti Army escaped south, across the desert border, into Saudi Arabia. (Voght, p.24)

In the 2:00 a.m. darkness of August 2, 1990, the Army of Iraq invaded its tiny oil-rich neighbor, Kuwait. The attack, spearheaded by tanks and troops of the elite Republican Guards Forces Corps, encountered only slight resistance. Within twenty-four hours, the capital, Kuwait City, was completely under Iraqi control. Only a few scattered remnants of the Kuwaiti Army escaped south, across the desert border, into Saudi Arabia. (Voght, p.24)