The search for national security strategy periodically opens major policy debates that push us in new, sometimes revolutionary directions. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the cold war have reopened a national debate unmatched since the end of World War II. Dramatic changes in the international system have forced us to reevaluate old strategies and look for new focal points amidst the still unsettled debris of the bipolar world.

At issue is America's role in a new world order and our capabilities to defend and promote our national interests in a new environment where threats are both diffuse and uncertain, where conflict is inherent, yet unpredictable.

The degree of uncertainty requires flexibility in our military strategy and significant departures from cold war concepts of deterrence. This study examines new options for deterrence. Its primary thesis is that new conditions in both the international and domestic environments require a dramatic shift from a nuclear to a conventional force dominant deterrent. The study identifies the theories and strategies of nuclear deterrence that transfer to modern conventional forces in a multipolar world.

One analytical obstacle to that transfer is semantic. The simultaneous rise of the cold war and the nuclear era gave rise to a body of literature and a way of thinking in which deterrence became virtually synonymous with nuclear weapons. In fact, deterrence has always been pursued through a mix of nuclear and conventional forces. The force mix changed throughout the cold war in response to new technology, anticipated threats, and fiscal constraints. There have been, for example, well-known cycles in both American and Soviet strategies when their respective strategic concepts evolved from nuclear-dominant deterrence (Eisenhower's "massive retaliation" and its short-lived counterpart under Khrushchev), to the more balanced deterrent (Kennedy to Reagan) of flexible response which linked conventional forces to a wide array of nuclear capabilities in a "seamless web" of deterrence that was "extended" to our NATO allies.

Early proponents of nuclear weapons tended to view nuclear deterrence as a self-contained strategy, capable of deterring threats across a wide spectrum of threat. By contrast, the proponents of conventional forces have always argued that there are thresholds below which conventional forces pose a more credible deterrent. Moreover, there will always be nondeterrable threats to American interests that will require a response, and that response, if military, must be commensurate with the levels of provocation. A threat to use nuclear weapons against a Third World country, for instance, would put political objectives at risk because of worldwide reactions and the threat of horizontal escalation.

The end of the cold war has dramatically altered the "seamless web" of deterrence and decoupled nuclear and conventional forces. Nuclear weapons have a declining political-military utility once you move below the threshold of deterring a direct nuclear attack against the territory of the United States.

As a result, the post-cold war period is one in which stability and the deterrence of war are likely to be measured by the capabilities of conventional forces. Ironically, the downsizing of American and Allied forces is occurring simultaneously with shifts in the calculus of deterrence that call for conventional domination of the force mix.

Downsizing is being driven by legitimate domestic and economic issues, but it also needs strategic guidance and rationale. The political dynamics of defense cuts, whether motivated by the desire to disengage from foreign policy commitments or by the economic instincts to save the most job-producing programs in the defense budget, threaten the development of a coherent post-cold war military strategy. This study identifies strategic options for a credible deterrence against new threats to American interests. Most can be executed by conventional forces, and present conditions make a coherent strategy of general, extended conventional deterrence feasible.

Critics of conventional deterrence argue that history has demonstrated its impotence. By contrast, nuclear deterrence of the Soviet threat arguably bought 45 years of peace in Europe. The response to this standard critique is threefold:

First, conditions now exist (and were demonstrated in the Gulf War) in which the technological advantages of American conventional weapons and doctrine are so superior to the capabilities of all conceivable adversaries that their deterrence value against direct threats to U.S. interests is higher than at any period in American history.

Second, technological superiority and operational doctrine allow many capabilities previously monopolized by nuclear strategy to be readily transferred to conventional forces. For example, conventional forces now have a combination of range, accuracy, survivability and lethality to execute strategic attacks, simultaneously or sequentially, across a wide spectrum of target sets to include counterforce, command and control (including leadership), and economic.

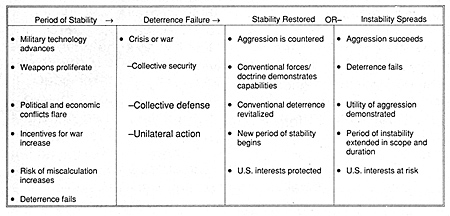

Third, critics of conventional deterrence have traditionally set impossible standards for success. Over time, any form of deterrence may fail. We will always confront some form of nondeterrable threat. Moreover, deterrence is a renewable commodity. It wears out and must periodically be renewed. Deterrence failures provide the opportunity to demonstrate the price of aggression, rejuvenate the credibility of deterrence (collective or unilateral), and establish a new period of stability. In other words, conventional deterrence can produce long cycles of stability instead of the perennial or overlapping intervals of conflict that would be far more likely in the absence of a carefully constructed U.S. (and Allied) conventional force capability.

How we respond to deterrence failures will determine both

our credibility and the scope of international stability. Figure 1

summarizes what seem to be reasonable standards for judging

conventional deterrence.

How we respond to deterrence failures will determine both

our credibility and the scope of international stability. Figure 1

summarizes what seem to be reasonable standards for judging

conventional deterrence.

Long periods of stability may or may not be attributable to the success of deterrence. In any case, no deterrence system or force mix can guarantee an "end to history." Paradoxically, stability is dynamic in the sense that forces are constantly at work to undermine the status quo. Those forces, also summarized in Figure 1, mean that deterrence failures are, over time, inevitable. Readers may have difficulty associating column 1 (Figure 1) with periods of "stability." Regrettably, in international politics that's as good as it gets.

The United States should, therefore, base its military strategy on weapons that can be used without the threat of self- deterrence or of breaking up coalition forces needed for their political legitimacy and military capability. If we are serious about deterring regional threats on a global scale, this strategic logic will push us into a post-cold war deterrence regime dominated by conventional forces.

More Deterence and Conventional Military Forces

- Introduction

A Conventional Force Dominant Deterrent

Role of Nuclear Weapons in a Conventional Force-Dominant Deterrent

Back to Table of Contents Deterrence and Conventional Military Forces

Back to SSI List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by US Army War College.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com