They waited a few days but no attack

came. Colonel Juan Jose Mendez now

commanding what was left of the Fourth

Division sent out two guerrillas of 400 men

each to reconnoiter the road to Izamel.

Approaching cautiously the Ladinos entered the

burned remains of the town, meeting and

dispatching only a few Mayan looters. The

enemy had gone. In the south the aggressive

Colonel Cetina also pushed his men forward in a

successful raid against Ticul to find that the

enemy was withdrawing. Merida went wild with

joy at the news of their salvation. To top off the

good news contact was made with Colonel

Pasos and the "lost" Third Division. Pasos had

been so hotly engaged with the Maya that he

didn't have the time to contact headquarters.

In later years the son of a Maya leader

explained what happened. As the Maya

prepared to take Merida [4]:

... [the Maya] talked among

themselves and argued, thinking deeply,

and then when morning came ... my

fathers people said, each to his Batab

[leader] ... I am going - and in spite of

the supplications and threats of their

chiefs each man rolled up his blanket

and put it in his food pouch, tightened

his sandals and started for his home and

his cornfield.

[The Mayan commanders]

knowing how useless it was to attack

the city with the few men that

remained, went into council and

resolved to go back home. Thus true to their annual tradition and the

native way of thinking, the Maya returned

home to attend their overdue spring planting.

They had lost the race to capture Campeche

and Merida before the rains came but they did

not think it important. The Maya while master

guerilla tacticians had no concept of strategy.

They did not think that the Ladinos could

recover their strength and simply felt

Campeche and Merida could wait till after the

already late planting, besides they would have

to eat the next year. So they lost their best

chance for driving the hated white man

completely from their land. At heart the

Mayans are farmers, not soldiers.

The few disciplined fanatics that

remained continued to raid; burning fields within

sight of Campeche and pressing the their

attacks to within 17 miles of Merida. But the

enemy they encountered was a revitalized

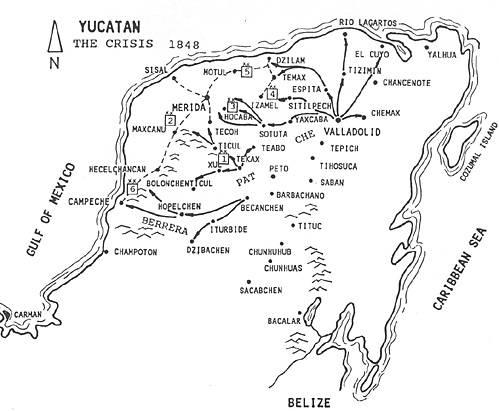

Yucatecan army. Following up his initial

success against Izamel Colonel Mendez

(exceeding his orders) drove up the Valladolid

road with a 1200 man column to take Tunkas

halfway to Valladolid. Setting up a base he sent

small guerrillas to follow, track, or pursue, the

dispersing Maya to their homes and cornfields a

potentially devastating strategy.

To the south around Ticul Jacinto Pat with

some foresight and generally better disciplined

troops had managed to keep a large part of his

force intact. Here he faced the aggressive

Colonel Cetina throughout June and July in a

seesaw struggle of ambushes, raids and counter

raids. Finally on July 29 Pat tired of the struggle

and withdrew his battered forces. He

conducted a tenacious fighting withdrawal

toward Peto through Ticul and Tekax. After

Tekax fell to a Ladino pincer movement, Cetina

in true Caste War fashion had the Maya

prisoners whipped, and then ordered them

(including children) tossed from the balcony of a

public building onto waiting bayonets below.

Fighting was also heavy elsewhere. In the

central sector the Cocome Maya still besieged

the small town of Huhi eight miles south of

Hocaba. Opposed by the hard fighting troops of

Colonel Pasos' Third Division, the Cocome gave

up the siege and abandoned Yaxcaba and Sotuta

as they fell back.

Around Campeche the faint hearted

garrison discovered they were opposed by only a

few stray marauders and became more

aggressive. The Sixth Division, newly raised

from the villages along the Campeche-Merida

road took up the offensive against Hopelchen

where after heavy fighting t ey established a

fortified camp.

By August the tide had definitely turned for

the Ladino defenders. The counter offensive had

recovered much of the frontier as far as Tunkas,

Sotuta, Yaxcaba, Tekax, and Hopolchen.

Outside assistance in the form of foodstuffs and

weapons from Cuba and the United States, were

arriving in quantity. Governor Barbachano was

able to assure Mexican assistance by

renegotiating terms of reunification with the new

Mexican government. Reunification with Mexico

was announced on the 17th of August.

For the Maya August meant the end of

planting and the return of the warriors to the

front. Cecilio Che took some 5000 of his

reassembled warriors and set out to recapture

Yaxcaba. Here the fighting resembled that of the

previous year with aggressive Ladino sorties

being chopped up by the Mayan besiegers.

After some touch and go fighting the

Ladino's fell back on Sotuta. The Maya followed

up but a large influx of Ladino reinforcements

discouraged the would be siege and the Indians

melted away into the forest. The Ladino's were

able to reoccupy Yaxcaba.

The Ladino success during the summer

campaign reflected an improvement in Ladino

tactics and fighting skills as well as a decline in

Indio morale and unity. The Ladinos now

deployed their forces in a more coordinated

"hedgehog" fashion. The forward fortified camps

were deliberately kept small so as to be self

supporting by local foraging which also denied the enemy local

crops. These positions were also mutually

supporting; when one camp was threatened,

nearby posts would send help ideally striking the

enemy rear. In bush fighting the Ladino veterans

were now better at utilizing cover and

concealment, and more adept at flanking those

pesky Indian barricades. Even the Maya

noted the improvement: "we think we will

surprise them in our ambushes, we are the ones

who are surprised in the rear." [5]

In contrast among the Maya Leadership

there was increasing dissention. Pat and Che, of

course, never got along and among Pat's

command a prominent Batab in Peto was

executed for suggesting surrender.

In another incident a Batab received 200

lashes for losing a position entrusted to him.

These were sure signs morale was slipping.

Worst, as the Yucatecan Fifth Division

advanced to Tizimin they offered amnesty and

for the first time Batabob (pl.) and their entire

families were surrendering.

As the autumn approached General Llergo

prepared to launch his grand offensive; a

coordinated effort by the First, Second, Third,

Fourth, and Sixth divisions to sweep the Cocome

region and converge on Peto. The Third and

Fourth divisions concentrated around Yaxcaba

moved south via Tiholop and Tinum, fighting

their way into position east of Peto. Advancing

from Teabo the Second and Sixth divisions met

heavier resistance and were bogged down in

extended skirmishing. The First Division striking

from Tekax however made rapid progress after

smashing Berrera's defenses and captured Peto

unopposed on October lst, later to be joined by

the delayed Second and Sixth Divisions.

With the Indians in general withdrawal the

advance continued after a month's pause to

secure and organize the rear area and lines of

communication. In rapid secession Progreso,

Dzonotchel, Sacala, and Ichmul were

recaptured. By the end of the year Tihosuco

and Valladolid fell undefended, followed by

Chancenote and Chemax. Only Bacalar of the

Ladino settlements remained in Maya hands

and it would fall the next year. The reconquest

of the frontier was complete.

Machete and Musket Part II The Yucatan Indian Uprising 1847-1855

As May came to an end the Ladino

defenders deployed in an arc around the

environs of Merida girded themselves for the

final onslaught. By now those that remained to

man the defenses were the true fighting men

"the garrison heroes; parade officers were

gone". [3]

As May came to an end the Ladino

defenders deployed in an arc around the

environs of Merida girded themselves for the

final onslaught. By now those that remained to

man the defenses were the true fighting men

"the garrison heroes; parade officers were

gone". [3]

... the sh'mataneheeles

[winged ants, harbingers of the first

rains] appeared in great clouds ... all

over the world. When my fathers people

saw this they said ... "the time has come

for us to make our planting,for if we do

not we shall have no Grace of God to fill

the bellies of our children".

Back to Table of Contents -- Savage and Soldier Vol. XXIII No. 2

Back to Savage and Soldier List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by Milton Soong.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com