February 1848, the beginning of the

harvest season saw the Maya poised to

break through the frontier at three points:

Valladolid in the north, Sotuta in the center

and Tekax in the south.

February 1848, the beginning of the

harvest season saw the Maya poised to

break through the frontier at three points:

Valladolid in the north, Sotuta in the center

and Tekax in the south.

Matthew Calbraith Perry, 1834; portrait by William Sidney Mount

The Ladinos finally realized the gravity of the crisis they were facing. At Mexcanu, new seat of the Mendez government (Merida was considered politically unreliable), Barbachano and Mendez, the leaders of the two divisive factions met and made a formal reconciliation in a show of Ladino unity.

Soon afterwards Barbachano was sent south with a cavalry escort to Tekax, commissioned by the government to seek out Jacinto Pat (the more reasonable of the Maya leaders) and discuss peace terms. In discussing terms the Ladinos would be relying on the intercession of the Church. The Maya considered themselves Christians and still had great respect for the church - to the point where they usually spared captured priests.

The Initial response to the peace overtures was favorable Jacinto Pat presented reasonable terms that were acceptable to the Government. The Cocome Mayan leaders besieging Sotuta accepted a truce and even the bloodthirsty Cecilio Che besieging Valladolid agreed to an armistice after consulting with Pat and the other Mayan leaders.

The fragile truce around Valladolid agreed to on February 12th was to be short lived. Two days earlier 2000 Maya from the Valladolid siege lines descended on the Ladino town of Chancenote, remotely situated forty miles to the northeast and heretofore unmolested by the Indios. The seventy man garrison fell back with the women and children into the walled churchyard where they held out until their powder gave out. They then attempted a breakout into the woods but most were cut down in the attempt.

Overrunning the churchyard, the Indians raped, slaughtered, looted, and burned. In the confusion and the smoke of the burning church, 25 survivors who had hidden on the church roof made their escape to spread the news of the latest Mayan atrocity. A week after the armistice, news of the Chancenote massacre reached Valladolid.

Since the Mayan encirclement of Valladolid the previous month three convoys of badly needed supplies had fought their way into the city reinforcing the garrison with some 300 troops. The Ladinos, angered by the Chancenote massacre, felt strong enough to launch a sortie. Without telling the Maya that the truce was over, a hundred men under Col. Victoriano Rivero drove into the outlying village of Chichimila scattering the surprised Mayan defenders. Typically the Ladinos overextended themselves and reinforcements from the garrison had to extricate them from the Mayan counterattack.

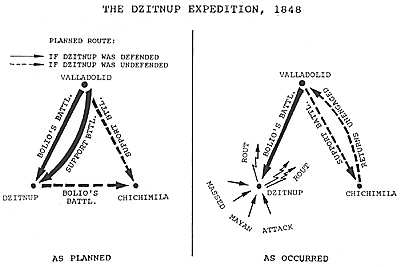

On February 25th, Rivero led a battalion

sized expedition against Dzitnup eight miles to

the southwest. On reaching the abandoned

town the column was attacked from all sides

and routed back to the garrison with light

losses.

On February 25th, Rivero led a battalion

sized expedition against Dzitnup eight miles to

the southwest. On reaching the abandoned

town the column was attacked from all sides

and routed back to the garrison with light

losses.

The garrison's morale sunk with these setbacks. To regain the initiative and restore morale a new stronger sortie against Dzitnup was called for. This time in a more complicated plan one battalion of fresh troops under Col. Miguel Bolio would march on Dzitnup to lure the Maya into battle. A second battalion would remain behind in ready support. If Bolio found the village of Dzitnup undefended he was to set fire to the place as a signal to the reserve column. Both columns would then converge on the village of Chichimila (believed to be the Maya headquarters), two miles east of Dzitnup. Should Bolio's column meet resistance at Dzitnup a lookout posted in the Valladolid Church tower would alert the second column which would then rush to Bolio's support. Either way, it was hoped, the elusive Maya would be forced to fight allowing the Ladino's to concentrate a large force against them.

Bolio's battalion (actually a composite force scratched together mainly from the 16th Campeche, the 1st Local, and Valladolid Battalions) set out in the early morning. The column's advance became less enthusiastic as they encountered badly mutilated remains of the enemy's previous victims. They were briefly fired at once by some Mayan skirmishers before reaching Dzitnup. Finding the village undefended Colonel Bolio deployed around the defendable churchyard, placed his outposts, and prepared to fire the town.

Suddenly the trap was sprung! The Maya charged out from concealment and rushed through the streets setting fire to huts to create smoke and confusion. The Ladino outposts were driven back on the churchyard. One group tried to make a stand in the plaza but was wiped out. From the churchyard Colonel Bolio tried to organize a counterattack. The Ladino attack barely cleared the walls before breaking. The defenders panicked and the Maya came on. Colonel Bolio went down sword in hand under a flurry of machetes, as the remains of his scattered battalion fought its way out of the town.

The smoke from the Dzitnup fire must have confused the Valladolid lookouts. Seeing the smoke as the prearranged signal that Dzitnup was undefended the supporting battalion proceeded as planned to Chichimila. Finding that village empty they returned without incident. Amazingly about half of Bolio's force made it back to Valladolid in small groups.

The second Dzitnup disaster was the final straw for Colonel Leon. The garrison commander ordered preparations for the eventual evacuation of the city.

On March

10th a last attempt to reopen negotiations with

Cecilio Che ended in bloodshed when Colonel

Rivero and a party of officers and priests went

out to meet with an Indian delegation. The

whites were seized and brought before Che who

spared the priests but had the officers

macheted.

On March

10th a last attempt to reopen negotiations with

Cecilio Che ended in bloodshed when Colonel

Rivero and a party of officers and priests went

out to meet with an Indian delegation. The

whites were seized and brought before Che who

spared the priests but had the officers

macheted.

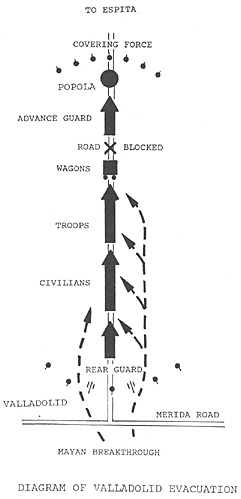

In Valladolid after some fairly elaborate planning the main and final evacuation was set for the morning of March 19th. At dawn, after a preliminary bombardment, a 500 man battalion assaulted the Maya barricades covering the Espita trail leading northwest. They successfully cleared the trail up to the village of Popola where they deployed to cover the main column. Bugles signaled that the way was clear and the advance guard was followed by a mass of wheeled traffic: wagons, carts, carriages and litters carrying supplies and the wounded.

The main body of troops came next followed by the 10,000 remaining citizens. The rear guard trailed after them covered in turn by artillery and a thin skirmish line of infantry.

By seven that morning most of the city had been cleared but up ahead on the wooded trail a carriage broke down and the column came to a halt. Back in Valladolid the Maya had already penetrated the southern barrios of the abandoned city, burning as they went. They soon crossed north of the main Merida road. Here among the northern barrios the Ladino skirmishers fell back on Colonel Leon and the rear guard which protected the last of the civilians, still waiting for the road to clear.

Grapeshot from Leon's cannon kept the back streets clear. To avoid the cannon fire the Maya infiltrated through buildings and courtyards. Suddenly they were among the rear guard and civilians. The rearguard disintegrated and the Indios were soon butchering the civilians along the length of the column.

Colonel Leon managed to fight his way to the front of the column still stalled at Popola. Here he had the gunpowder supplies destroyed to keep them out enemy hands and ordered all vehicles abandoned so as to get everyone moving again. Rallying a few brave souls around a cannon that was manhandled through the wagon jam, Leon managed to reconstitute a skeleton rearguard as the demoralized mass of civilians and soldiers surged past him.

It took the survivors three days to negotiate the 30 miles to Espita. At Espita Leon tried to organize a new defence line but his demoralized troops refused to stand. Most of them like the survivors of the Campeche Battalion just wanted to go home. Leon had no choice but to lead them back to Merida.

The fall of Valladolid presaged the collapse of the frontier, that same month Sotata was abandoned. The Mendez government resorted to a desperate measure to gain foreign assistance. In separate communications to the governments of Spain, Great Britain, and the United States the Yucatecan government offered complete "domination and sovereignty" over Yucatan to the first power to offer "powerful and effective help".

In Washington the Polk administration seriously considered the offer and made a point of invoking the Monroe doctrine to prevent other foreign powers from accepting the offer. The "Yucatan Aid Bill" eventually foundered in congress but the publicity led to the arrival of American volunteers in Yucatan.

Back in Yucatan more practical measures were taken to face the inevitable Mayan onslaught. A major shipment of Spanish arms was landed at Sisal and it was time for a change in government. Mendez resigned the governorship in favor of Barbachano who tried one more ploy to buy time.

Along the southern front the negotiations with Jacinto Pat had not yet broken down and through him the Yucatecans hoped to create a split between the two major Maya leaders: the fanatical Cecilio Che and the moderate Jacinto Pat.

At a parley on April 18th the Ladino commissioners and Jacinto Pat agreed to a treaty that promised a number of social and tax reforms. The treaty made Barbachano (the only white leader acceptable to Indians) governor for life, and appointed Jacinto Pat "Gran Cacique de Yucatan", sort of a native governor. The Ladinos gave Pat a banner embroidered with his new title and quickly ratified the new treaty.

The Ladino ploy worked briefly. Still heady after his victory at Valladolid, an enraged Che accused Pat of treachery and took out his frustration by leading his men south and massacring 200 people at Mani only ten miles from the parley tent at Ticul.

His men confronted a surprised Pat at his headquarters and burned the embroidered banner. This effectively nullified the treaty and ended any treaty making between the whites and Indians. Soon afterwards Tekax was evacuated. The crisis was at hand.

Machete and Musket Part II The Yucatan Indian Uprising 1847-1855

Back to Table of Contents -- Savage and Soldier Vol. XXIII No. 2

Back to Savage and Soldier List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by Milton Soong.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com