Back in February after the fall of Peto,

the government appointed a distinguished

veteran of the Mexican wars, General

Sebastian Lopez dc Llergo, commander of all

Yucatan forces. The new commander now

faced a formidable task. Since the fall of

Valladolid desertions and mutiny were rife

among the Yucatecan forces. Working with

what troops remained and with what could be

raised from the refugees assembling on the

coast General Llergo took advantage of the

armistice lull to organize a new defense line.

Back in February after the fall of Peto,

the government appointed a distinguished

veteran of the Mexican wars, General

Sebastian Lopez dc Llergo, commander of all

Yucatan forces. The new commander now

faced a formidable task. Since the fall of

Valladolid desertions and mutiny were rife

among the Yucatecan forces. Working with

what troops remained and with what could be

raised from the refugees assembling on the

coast General Llergo took advantage of the

armistice lull to organize a new defense line.

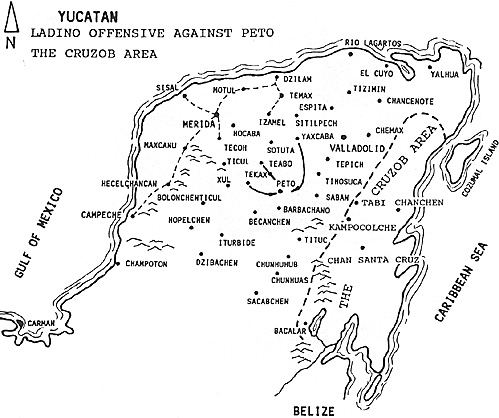

Llergo regrouped the various militia

battalions and companies into five divisions

which were deployed in a wide arc covering the

capital. [1]

The First Division, some 1,800 men under

Col. Alberto Morales defended the southern

approaches at Ticul. The Second Division

was placed in reserve at Mexcanu under Colonel

Leon. Col. Jose Delores Pasos commanded the

Third Division at Hocaba. The Fourth

Division defended Izamel under Col. Carmen

Bello, while Col. Jose Cosgaya's Fifth Division

held Motul. A Sixth Division was later organized

to defend the approaches to Campeche. Back in the capital Barbachano made

preparations for a mass evacuation of the

Peninsula should these defenses fail.

With the peace talks ended, the Mayan

offensive picked up steam in the center with a

drive against Ticul on May 17th. The First

Division defending Ticul received newly raised

reinforcements from Merida commanded by the

notorious Col. Jose Cetina (back in favor with

the new government). Cetina took command of

the defensive operations around Ticul; improving

the defenses with new artillery emplacements

covering the three main roads, and launching

aggressive but ineffective sorties against the

encircling Maya.

Anticipating the encirclement of Ticul a

force under Col. Pablo Antonio Gonzalez had

been stationed at Sacalum eight miles to the rear.

Their orders were to keep open the supply line to

Ticul. In a series of confused actions Gonzalez

managed to get one supply convoy through to

Cetina but in the process lost his own base at

Saculum where the inhabitants were massacred.

The demoralized troops ran fled back to Merida.

Gonzalez managed to raise a new force from the

refugees there and marched south again to

recover Saculum.

Back at Ticul, Cetina was running low on

ammunition and the Maya barricades were

creeping closer. After five days without relief

Cetina decided on a breakout. The evacuation

followed the now typical pattern. Cetina led the

breakthrough against the northern lines. The

advance guard established a forward screen at

the Hacienda San Jose. The rearguard, a

Ticul militia battalion, was hard pressed by the

Maya and collapsed. the result was a repeat of

the Valladolid road. Cetina managed a stand at

San Joaquin and the retreat continued after dark

to Uayalceh just 17 miles from Merida. The

Maya were too busy looting San Joaquin to

pursue any further.

In the northern sector Cicilio Che massed

his forces against the 4th division holding Izamel.

Taking Dzilim to the north in early May, Che

went on with another column to besiege Sitilpech

a few miles east of Izamel.

On the 14th Col. Carmen Bello

commanding at Izamel first sent one battalion

reinforce Sitilpech. It was stopped dead in its

tracks. Another Battalion was committed and

the combined force fought its way to Sitilpech

to extricate the decimated garrison there. Less

than half the force made it back to Izamel. A

week later the sole survivor of a scouting

patrol reported that the road to Merida was

cut and Izamel surrounded.

Carmen Bello had enough supplies but the

garrison's morale was brittle and after a week

of siege and fighting at close quarters he opted

for the inevitable evacuation. On the 28th he

pulled out his thousand man garrison in a well

executed night withdrawal along a poorly

guarded back trail. The Maya cautiously

followed up and burned the town after paying

their devotions at the cathedral.

The Mayan drive in the south was led by

the capable Jose Maria Beffera, one of Pat's

lieutenants who would eventually become the

dominant Mayan leader. His initial force of

3000 from the Puuc hills had swollen by

thousands more local recruits as he pressed

toward the coast. In April he had overrun the

Chenes region and early May brought his

advance forces to the walls of Campeche.

General de Llergo watched his patchwork

defense line crumble. The last days of May saw

Ticul, Saculum, and Izarnel fall; Campeche and

Merida directly threatened; and to worsen

matters Colonel Pasos' Third Division at

Hocabo was cut off and not heard from since.

News arrived by steamer that Bacalar far

behind the lines near the Caribbean coast had

also fallen.

On the north coast the fifth Division in

danger of encirclement was ordered to abandon

Motul and cover the vital escape route to the

port of Sisal. The final defense of Merida would

rest with the First and Second divisions holding

Uayalcheh and Tecoh but their morale was

shaky at best, while some of the other divisions

were outright mutinous.

Half of Carmen Bello's Fourth division,

those from Campeche, mutinied and abandoned

their positions for the protective walls of

Campeche. In Campeche the French consul

wrote how the city would surely fall and that the

militia garrison was demoralized.

Offshore the American bomb-brig

Vesuvius and other ships of Commodore

Matthew Perry's Gulf Squadron stood ready to

evacuate U.S. citizens. The Yucatecans

petitioned Commodore Perry for U.S. Marines to

land and maintain order if not to fight Mayans.

Further south in another refugee center, the

remote Island port of Carmen, 300 U.S. Marines

from offshore ships were detailed to provide

protection. Perry a close observer of events

wrote his government

[2] :

Though he considered the Ladinos an

"extraordinary example of disgraceful

cowardice" and noted "they have become panic

striken and seem to have lost all courage" Perry

did advocate their cause; requesting permission

to garrison Campeche with bluejackets. This was

vetoed by President Polk who did not wish to

intervene in a civil war, though Perry was

authorized to proctect Carmen if it was

threatened. Perry ordered his ships to land a

supply of powder and some 1000 captured

Mexican muskets at Campeche and to rescue

stranded refugees along the coast.

Merida and the crowded coastal ports

where over a hundred thousand refugees

huddled, were in a state of acute anxiety if not

panic. Llergo contemplated a fighting withdrawal

to Sisal and a final stand behind the walls of

Campeche. Governor Barbachano packed his

bags and prepared his proclamation of the

evacuation of Merida but could find no paper for printing it. Among

the general population the fear of a general

slaughter was on the verge of realization.

Machete and Musket Part II The Yucatan Indian Uprising 1847-1855

...that the inhabitants of

Campeche are preparing to abandon

that stronghold to the indians. The [US.

State] Department is, I presume, aware

that Campeche is a strongly fortified

place, being entirely surrounded by

thick and high walls, rendering it

defensible against a very large force,

especially of half-armed Indians,

unprovided with a

battering train.

Back to Table of Contents -- Savage and Soldier Vol. XXIII No. 2

Back to Savage and Soldier List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by Milton Soong.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com