Historical Themes

Undertaking the daunting task of conquering the Persian empire, Alexander solved the problem of providing homeland security. His solution was to place his father's most trusted companion and advisor, Antipater, in command at Pella with a garrison of six brigades of phalangites. These troops were replaced in Alexander's army by a mixed force of allied Greek hoplites and Greek mercenaries totaling at least 12,000 spears.

Thus, the pool of manpower available to recalcitrant Greek cities was drawn down by the resources marching with Alexander. With the concomitant recruitment of Greek mercenaries to fill the ranks of Darius III's army, the prospect of rebellion in Greece was significantly reduced.

A second member of the Philipic braintrust, Antigonos, whose role in Alexander's success has been little appreciated (see Billows [1990]), commanded most of the Greek contingent. The tactical role of these Greeks was very important at Gaugamela. There, Alexander - or was it Antigonos -- improvised a tactical deployment not generally seen in western warfare until the legionary quincunx of the Roman Republic: the Macedonian army was deployed in two supporting lines, a frontline of pikemen backed up by a secondary line of Greek spear. The secondary line provided the foundation for the echelon attack Alexander employed, it being a reserve formation available to offset counter-flanking movements by the Persians.

That the Persians would attempt to out-flank Alexander may be taken with certainty, given the degree to which the Macedonian front had to be shortened in order to populate a second line. Alexander had correctly surmised the Persian wings would overextend as they reacted, creating gaps to be exploited by his shock cavalry, massed on the right of the concentrated Macedonian host. Thus went the battle of Gaugamela, sealing the fate of the Achaemenid clan.

The part played by the third member of Philip's inner circle, Parmenion, was intentionally obscured in the original ancient sources. It is clear from those sources that he was usually the commander of the left wing and a close advisor to Alexander. It also clear that his thematic role in those texts is the dumbed-down foil to Alexander's ex post facto genius. Regardless, it appears likely that his presence with the field army was too important for his own good, as he contributed much to Alexander's success before being ruthlessly purged as that success was finalized.

Tactics

There is ample reason to argue that the single most successful tactic employed by Alexander was an impetuous charge by the Hetairoi led by Alexander himself, directed at a key segment of the enemy's line. This implies the best countermeasure may be a trap to bag the Macedonian king, as the Persians attempted to do at the Granikos. There is a special heroic general special rule listed below.

Otherwise, as noted above, the Macedonians deployed in two lines, pike in front, hoplites to the rear. The Royal army, historically the army's striking force, was advanced on the right; the allied cavalry, including the superb Thessalian cavalry, were refused on the left. Since the army is relatively lightly armored, care must be exercised against missile-heavy enemies, especially the close order bows of the Indians. Use the light artillery, Cretan and Macedonian archers, and the Agrianes and Thracians to screen the army's advance. If the pike maintains its good order, it will defeat most opponents.

Historically, this army suffered from a shortage of light cavalry, which may not be obvious in the close confines of a 25mm tournament table. The army's cavalry is best utilized sheltered behind the infantry until a target of opportunity presents itself.

Enemies Later Achaemenid Persian. Later Hoplite Greek, Later Illyrian, Thracian.

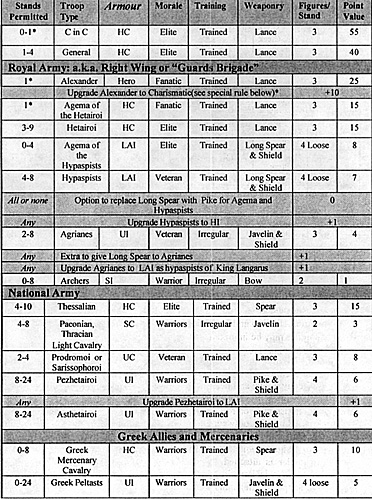

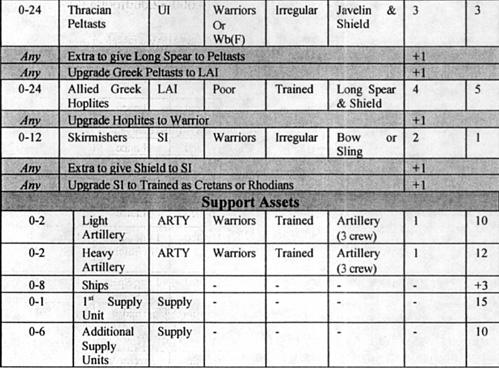

Alexander Invades Persia (40,000/32,000 foot/4,000 horse::200 stands/160 foot/40 horse)

Notes

- Minimums apply only if the Hero Alexander is used, in which case there is no CinC. Players may opt not to use Alexander, in which case the CinC is mandatory. The single stand of Fanatic agema may only be bought with an heroic Alexander.

- Prodomoi, Hetairoi and Thessalian cavalry may use wedge.

- Phalangites may be in mixed armor units.

- If any Thracians are given a second weapon, all must be equipped with one.

Heroic General Special Rule

The lists directly allow for the Hero, Alexander, but no CinC. How does this work in game terms? One can either pay 10 points and make Alexander charismatic, or roll for his character as per the usual general rules. The trick is, Alexander only functions as a CinC for dice rolling purposes, i.e. for terrain placement and initiative determination (each and every turn); he has no orders to assign to units apart from a single order he may give to any unit to which Alexander is attached.

Alexander's Hero stand is the agema of the Hetairoi (since he is Fanatic, and Frenzied within engagement range of the enemy, the scope of Alexander's control is obviously very limited). This rule simulates the notion that Alexander's battle planning was thorough and complex, but he left the actual direction of the battle to his very capable sub-ordinate generals, while he personally led the drive on the key position in the enemy's line. Finally, Alexander counts as General and CinC if he is killed or captured in combat.

Alternatively, one can pass on taking Alexander the Hero, and play instead with a straight-up CinC. In the latter case, there is no upgrade to charismatic (take your chances with the dice).

More Armies of Alexander the Great

-

Introduction and Technical Terms

Philip the Barbarian to 336 BC

Alexander Invades Persia 335-330 BC

Pursuit to the East 330-327 BC

India 326-323 BC

The Alexandrian Imperial Army, 323 BC

Back to Saga # 84 Table of Contents

Back to Saga List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Terry Gore

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com