This once great kingdom of 10 million people had long suffered under weak royal leadership, increasing financial hardship, and the consequent growing redirection of its colonial wealth to northern European financial houses. So, too, had Spain's once vaunted military prowess, on land and at sea, declined under the weight of royal patronage and aristocratic privilege, although the courage of the soldiers when well-led was evident even to the French.

The quality of royal advisors failed to escape a similar deterioration. King Charles III (1742-1819), a mediocrity with questrionable sanity, was dominated by his wife, Maria Louisa of Parma, and, from 1792, by her lover, Manuel Godoy (1767-1851), who rose from the House-hold cavalry to become the King's chief minister.

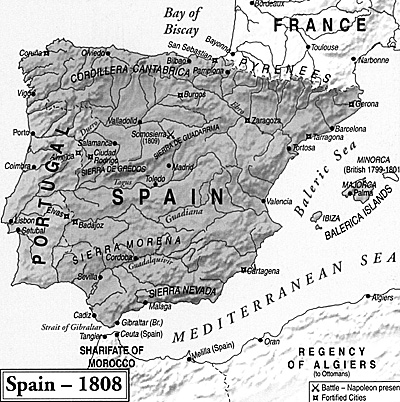

Spain joined the First Coalition against France in 1793 with the execution of the King of France (a fellow Bourbon), but was forced to make peace in 1795 and subsequently to ally with France from 1796. Spain's naval defeats jeopardized control of its substantial overseas colonies (already weakening in the Americas), and this was a source of enduring strain with Britain (whether hostile or allied) on the hunt for direct access to markets. While Spain's navy remained at the disposal of France, its army was little involved, except for the brief, farcical "War of Oranges" with Portugal in 1801.

The French invasion of Portugal in 1807, to enforce the Continental System, opened the door to the occupation of Spain as Napoleon's Imperial troops not only passed through, but also secured positions in Spain. Napoleon took advantage of intrigue and dissension within the Spanish royal family to induce both the King and his heir to resign their thrones, interned them in France, and proclaimed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, the new King of Spain in 1808.

The French invasion of Portugal in 1807, to enforce the Continental System, opened the door to the occupation of Spain as Napoleon's Imperial troops not only passed through, but also secured positions in Spain. Napoleon took advantage of intrigue and dissension within the Spanish royal family to induce both the King and his heir to resign their thrones, interned them in France, and proclaimed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, the new King of Spain in 1808.

This proved too much for a proud people, and Spain rose in popular revolt in May, igniting a long and brutal "war of independence" from which was born the popular term "guerrilla" -- the little war.

Spanish armies proved to be no real battlefield threat to the French, although they did score several victories, including the capture of an entire French army corps at Baylen in 1808. Their resilience and that of Wellington's allied Anglo-Portuguese army required repeated concentrations of French troops to attempt to deal with them, while popular resistance and various guerrilla bands throughout the country required dispersion of French troops into numerous garrisons.

It was a dilemma that neither Napoleon's brother nor the marshals he sent to Spain ever solved.

Napoleon's political miscalculation, his military mismanagement from Paris, and the failure to centralize French command created what came to be called his "Spanish ulcer", diverting hundreds of thousands of Imperial troops and draining the army of thousands of men every year.

Napoleon's political miscalculation, his military mismanagement from Paris, and the failure to centralize French command created what came to be called his "Spanish ulcer", diverting hundreds of thousands of Imperial troops and draining the army of thousands of men every year.

The war in the Iberian Peninsula slowly but critically undermined Napoleon's empire.

More Powers of the Napoleonic Era

- France

Great Britain

Duke of Wellington Profile

Austria

Archduke Charles Profile

Russia

Field Marshal Kutusov Profile

Prussia

Field Marshal Blucher Profile

Spain

The Peninsula War

Ottoman Empire

Minor Powers

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #17

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Napoleon LLC.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

Order Napoleon magazine direct