With only the 14-month interlude of the Peace of Amiens (1802-1803), Britain, Napoleon's most unappeasable foe, remained at war with France throughout the period. A constitutional monarch, George III (1738-1830) suffered from bouts with unstable mental health that from 1811 left his son (eventually George IV) as Prince Regent. Practical daily power resided, however, with the King's ministers. William Pitt, prime minister from 1783-1806, was the most noted head of government, while Robert Stewart, Lord Castlereagh (war minister 1805-1809, foreign minister 1812-1822) and George Canning (foreign minister 1807-09) subsequently played pivotal roles.

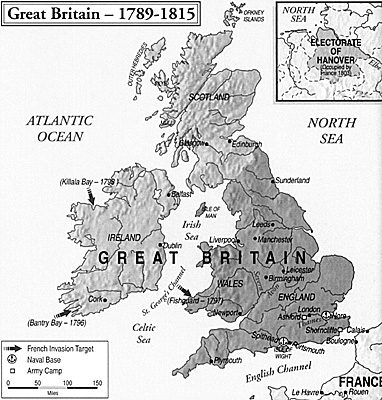

Britain faced several French invasion threats, two of which actually landed troops (at Fishguard, Wales in 1797 and Killala, Ireland in 1798). However, the planned invasion by Napoleon in 1803-1805 was the most worrisome. With some 15.5 million people (including five million Irish unified with Britain in 1800), most of Britain's military resources went to its indispensable fleet, which protected both Britain's shores and its commerce, for it was international trade that created England's wealth and constituted its sinews of power.

Britain's financial arsenal cannot be underestimated. Its commercial strength permitted the accumulation of an enormous debt, paying for war and subsidies, and engendered the imposition of income tax. By 1800, subsidies to allies, £3 million, constituted over 7% of total revenues; in 1813, £22.5 million in assistance to allies exceeded that year's expenditures on the Royal Navy.

By 1805, the Royal Navy had confined French fleets to their ports under close blockade and had won supremacy upon the sea. Meanwhile, Britain's small army was scattered across the globe occupied in colonial defense -- at a horrific expense: losses to disease and occasional combat cost roughly 90,000 troops in the West Indies alone.

By 1805, the Royal Navy had confined French fleets to their ports under close blockade and had won supremacy upon the sea. Meanwhile, Britain's small army was scattered across the globe occupied in colonial defense -- at a horrific expense: losses to disease and occasional combat cost roughly 90,000 troops in the West Indies alone.

Britain used its military to strike at the vulnerable, colonial wealth of its enemies. Unable to concentrate a large ground force in Europe, Britain engaged in pinprick Continental raids such as Quiberon Bay in 1795 and Copenhagen in 1807. Major forays were coordinated with allies such as Spain at Toulon in 1793 and Russia in southern Italy in 1805. Although the Royal Navy's capabilities were universally acknowledged, Britain's army was not respected -- incompetence and disaster during the Revolutionary and early Imperial years usually characterized its campaigns. Not until Britain's successful 1801 campaign against the remains of Napoleon's army in Egypt did the work of reformers begin to take effect.

Although a serious commitment in Italy was considered, the Spanish rising against French occupation in 1808, a traditionally friendly port obtainable in Lisbon, a Portuguese willingness to place its army under British control, a brilliant general (Wellington), and a politically supportive cabinet combined to make the war waged in the Iberian Peninsula and into southern France from 1808 to 1814 the British army's most valuable contribution to defeating Napoleon.

Although a serious commitment in Italy was considered, the Spanish rising against French occupation in 1808, a traditionally friendly port obtainable in Lisbon, a Portuguese willingness to place its army under British control, a brilliant general (Wellington), and a politically supportive cabinet combined to make the war waged in the Iberian Peninsula and into southern France from 1808 to 1814 the British army's most valuable contribution to defeating Napoleon.

From 1803, Hanover, of which George III was Elector, provided some 12,000 troops for what became the superlative King's German Legion, and from 1809, the little Duchy of Brunswick provided a small contingent in British service. Total naval dominance, a highly competent diplomatic corps, and substantial financial aid to its allies enabled Britain to forge no less than seven separate coalitions of allied nations against France that led to Britain's ultimate triumph.

More Powers of the Napoleonic Era

- France

Great Britain

Duke of Wellington Profile

Austria

Archduke Charles Profile

Russia

Field Marshal Kutusov Profile

Prussia

Field Marshal Blucher Profile

Spain

The Peninsula War

Ottoman Empire

Minor Powers

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #17

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Napoleon LLC.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

Order Napoleon magazine direct