17 June: The Retreat to Waterloo

As soon as he learned that the Prussians were in retreat from their defeat at Ligny, Wellington ordered a withdrawal. Bijlandt's Brigade played no part in the rear guard actions and arrived at Mont St. Jean early in the afternoon of the 17th. The brigade was positioned on the forward slope of the ridge of Mont St. Jean, in front of the sunken road leading to Ohain, northeast of the farm of La Haye Sainte.

That night, with rain pouring down in torrents, the men of Bijlandt's Brigade slept in the field without any food, since the civilian supplier was bankrupt and the baggage train was held up along the road from Brussels to Waterloo. Their sleep was also interrupted by several alarms throughout the night, caused by their nervous pickets who, in the exposed position on the forward slope, were standing near the French line. As they watched the French build-up to their front throughout the morning of the 18th, they also became aware of the fact that they had not received any resupply of ammunition.

When the Prince of Orange saw the miserable state they were in, he sent a detachment to the rear to find the ammunition wagons, and, if need be, to take them out of the traffic jam by force. The Prince also purchased some food so that the men could finally eat.

18 June: The Battle of Waterloo and Infamy

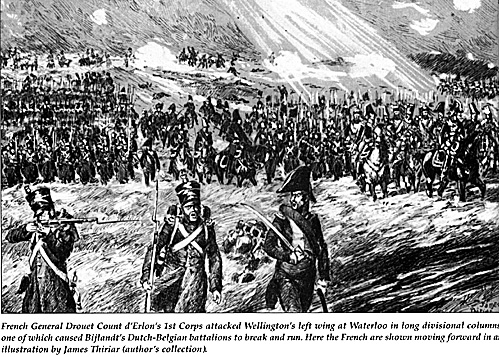

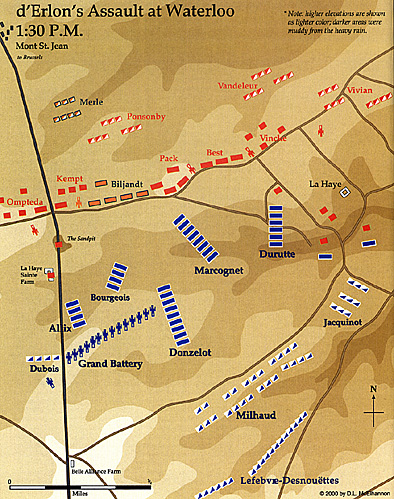

The position of Bijlandt's Brigade on the morning of the 18th was most extraordinary. It was the only body of Allied troops in the open on the forward slope of the ridge. The majority of the Anglo-Allied Army was positioned behind the ridge where it would be less vulnerable to artillery fire. The other troops in front of Wellington's main defense line were protected in some way, such as in the orchards and walled farm of Hougoumont.From 11:00 a.m. on, the French started to amass the grand battery of some 80 guns opposite Bijlandt's, Pack's, and Kempt's brigades in order to prepare for the attack by d'Erlon's 1st Corps. It became very evident to the Prince of Orange's staff that Bijlandt's men were in a dangerously exposed forward position. Fortunately, General de Perpon-cher received permission from the Prince of Orange to have the brigade fall in between Pack's and Kempt's British troops in the first line, behind the road to Ohain.

Col. van Nyevelt later reported of this movement before Napoleon's Grand Battery began its bombardment at about noon.

"At twelve o 'clock the whole of the first brigade [Bijlandt] and the artillery of the right wing moved further back in order not to hinder the evolutions of the English guns placed in their rear, and also to be less exposed to the fire of the enemy. Crossing the sunken road the corps formed itself on the northern side of the road in the battle array as before, supported on its right and left by the English and Scottish troops, the guns in line with those of the English" (Wommersom, part III).

The 5th Militia suffered so heavily at Quatre Bras that its 181 remaining men were placed in reserve behind the other battalions. Bijlandt's other four battalions stood in a two-file line immediately behind the hedged track that led to Ohain, the 7th Line and 27th Jdger Battalions adjoining Lt. General Sir James Kempt's 8th British Brigade, while the 7th and 8th Militia Battalions stood next to the Highlanders of the 92nd and 42nd Regiments in the 9th British Brigade under Major General Sir Denis Pack. The rest of Kempt's and Pack's brigades, part of Lt. General Sir Thomas Picton's 5th Infantry Division, were about a hundred meters behind Bijlandt's line, where the lower ground offered more shelter from the French artillery fire.

Here, the Dutch-Belgians stood when the French cannonade began. The bombardment lasted one and a half hours and inflicted further losses on Bijlandt's bloodied battalions. And now, the fresh infantry of d'Erlon's 1st Corps opposite them, which had not yet fought in the campaign, was preparing to attack.

At 1:30 p.m., d'Erlon's four divisions, covered on the flanks by brigades of French heavy and light cavalry, marched toward the ridge crest. One brigade of General Count Allix's 1st Infantry Division moved away from the fire coming from La Haye Sainte, which was occupied by King's German Legion (KGL) light infantry of Colonel Baron Ompteda's 2nd KGL Brigade. General Baron Donzelot's 2nd Infantry Division's column halted to avoid a collision with Allix's infantry, enabling the column of General Baron Marcognet's 3rd Infantry Division to take the lead. Captain van Bronkhorst of the 7th Militia Battalion wrote to his parents on 9 July about the French assault:

"At about 11 o'clock their operation [the preparations for the assault by d'Erlon's corps] was completed, as much as one could assume. You could see the French army taking possession of the heights along the valley that separated us. It was 10 or 11 o'clock. I had gone back with my company, the artillery started to fire, and soon one could observe the French descending into the valley. They were united in dense masses and were preceded by a great number of tirailleurs [skirmishers] who gave us many difficulties. The distance they had to cover before they had reached our heights was about half or three quarters of a mile.

In the space in between our lines they were exposed to our artillery fire and, as they progressed, to our musket fire. The bearing that they maintained was magnificent. None of these masses fell apart. Soon one could see them coming over the crest of the ridge at assault speed where our brigade lay in first line" (the letter was found among family papers and published in a Dutch military magazine: Ons Leger, 67e jaargang, June 1983, number 6, pages, 32-38).

When Marcognet's column reached the hedged track, it halted to deploy in line in order to maximize its firepower. Lieutenant Scheltens of the Belgian 7th Line described the exchange of this intense musket fire at close range:

"The battalion remained lying down behind the road until the head of the French column was at the distance of a pistol shot. Our battalion opened fire as soon as our skirmishers had come in. The French column imprudently halted and began to deploy. We were so close that Captain Henry l'Olivier, commanding our grenadier company, was struck on the arm by a musketball, of which the wad, or cartridge paper, remained smoking in the cloth of his tunic" (Souvenirs d'un Grognard Belge, page 201).

Colonel van Nyevelt also described what happened during and after the firefight: "Having approached us to within fifty paces, not a shot had been fired, but now the impatience of the soldiers could no longer be restrained, and they greeted the enemy with a double row of fire, against which the enemy bravely advanced. The brigade which the enemy attacked was ranged in a double line, which caused the fire to be weak and badly maintained, while the dropping down of a few files created an opening for the enemy through which he passed with his columns. Everything which was immediately in front of him was forced to give way ..... (report of Colonel van Nyevelt in De Bas and T' Sercleas de Wommersom, part 111, page 338).

Marcognet's troops crossed the sunken road to Ohain and began to ascend the ridge. They drove straight into the 7th and 8th Militia Battalions, still deployed in a two-deep line formation. Although neither battalion lost many men at Quatre Bras, the militia's morale was apparently fragile after the retreat to Waterloo, the awful, hungry night before the battle, and the effect of the French grand battery's bombardment. These two battalions broke like glass when the hammer of the French column hit them.

Captain van der Bruggen van Croy of the 7th Militia noticed how the French advance first induced the left wing of his battalion to give way, which then slowly spread to the right wing. However, the 7th did not retire further than some 100 paces, since their retreat was covered by the 5th Militia and a platoon of the 7th which was quickly assembled by Captain van der Bruggen and brought forward in skirmishing order (W. J. Knoop, page 214).

The rest of Bijlandt's Brigade recoiled in a hasty and quite disorderly fashion upon this second line. The fugitives were met with a volley of hisses and cries of 11shame" as they passed Picton's British troops. However, the British troops, being positioned behind the crest of the ridge, were not able to see what was going on in front of them and thus, apart from the intensive musketry, had no idea why the Dutch- Belgians were falling back.

As the men of Bijlandt's Brigade retired, Perponcher's staff and most of the officers of the brigade succeeded in rallying many of the troops, although several hundred could not be persuaded to stop (the 7th Militia lost more "missing" than any other Dutch-Belgian unit, 200 of its 675 men).

It would be unfair to characterize this action as simply a rout. Bijlandt's men fought before they fled, as supported in the killed and wounded totals in the tables accompanying this article. During the close-range combat, Lieutenant van Haren was killed, General Perponcher had two horses shot dead under him, and General van Bijlandt and Colonel van Nyevelt were wounded, as were several superior officers, among them the commanders of the 7th Line and the 5th and 7th Militia Battalions van den Sande, Westenberg, and Singenclonck - plus many noncommissioned officers. Captain van Bronkhorst related what happened then: "It was impossible to absorb the shock. We received orders to retreat behind the English troops who were in second line.

In those moments we suffered considerable losses. The French had reached the edge of the heights that we occupied. Scottish troops were determinedly waiting for them. The English cavalry which was positioned behind them saw that the moment for the charge had arrived and crossed the space which separated the masses of troops, hurled itself upon the French, and sabered down every resistance and took prisoners.

Never, oh, never shall I forget that moment when those formidable columns that went forward so proudly, with their heads raised and at a brisk pace, were cut to pieces. Those who escaped made an appeal to the kindness of the victors by throwing away their arms. There came a few additional columns to assist the assault of what they thought were the victorious columns. The English cavalry noticed them. Soon they underwent the same fate as their predecessors. In between these charges we had again occupied our places.

The terrain that we occupied was covered with dead and wounded, among them also a few of our own. Our first concern was to carry them off to the back and have them bandaged" (Ons Leger, June 1983, page 37).

Lieutenant Scheltens of the 7th Line also mentioned that his battalion took part in the countercharge: "The battalion, which had to cease firing, for the cavalry were in front, immediately crossed the road and advanced. The enemy, taken in flank by Picton's regiments and in reverse by the cavalry, was compelled to retreat, leaving behind a great many prisoners. The battalion then took up again its first position, where it remained to the end of the battle" (Souvenirs d'un Grognard Belge, page 202).

A Dutch veteran of the 7th Militia Battalion also mentioned the countercharge by his battalion: "The enemy hurriedly formed three squares against the English and Dutch cavalry, but we gained ground, went forward in skirmish order, the enemy backward in the same manner" (P. Wakker, page 13).

Colonel de Jongh, commander of the 8th Militia, took over command of the brigade after Bijlandt was wounded, but de Jongh could only do so by having himself tied to his horse due to the wound he had received at Quatre Bras. De Jongh reported: "At this moment [when the French overthrew the battalions in the first line] the English cavalry hacked into the French and sabered down two columns that had forced their way through our division. I assembled immediately the biggest part of my battalion, marched forward, and supported the attacks by the English cavalry, and we took many Frenchmen, officers and soldiers, prisoner" (Colonel de Jongh in De Nieuwe Spectator, page 6).

After their precipitous retreat the Dutch-Belgians of Bijlandt's Brigade rallied behind the 5th Militia Battalion and took part in the counterattack with the British cavalry. The French columns were also attacked on the flanks by Kempt's and Pack's infantry. In their enthusiasm the DutchBelgian soldiers followed the cavalry down the slope, across the valley, and close to the French lines until they were recalled. Colonel van Nyevelt reported:

"The enemy had now succeeded in passing our first line and had arrived on the plain. The second line made ready to advance against him, while a cavalry regiment of the English Guards came on the spot to harass him in case he was forced to retreat. Having penetrated so far the enemy then discovered large bodies of infantry which he had not been able to see from where he was, the troops having lain flat on the ground and been hidden by the hedge. While the enemy was rallying his forces in great haste the nearest troops of the second line [Kempt's and Pack's troops] attacked his flanks, supported in the movement by the Chief of Staff, who had been able to rally about 400 men of the troops which had been forced to retire.

"They succeeded in driving the enemy back over the low-lying ground, pursuing him with the bayonet even to his own ground, he being at the same time charged by the cavalry, who made great slaughter among the French. The Netherlands troops, carried away by their impetuosity, had gone far in advance of the English, and taken two flags [the fanions of the French 105th Infantry Regiment] from the enemy; but the fleeing troops of the enemy having turned their artillery upon them, all the detachments of the line returned to their old position" (see the report of Colonel van Nyevelt, page 338).

There was a great number of

French prisoners from d'Erlon's

failed assault, perhaps more than

3,000 men. The task of escorting the

French prisoners to Brussels was

given to Bijlandt's Brigade. As a

consequence, the brigade was

further depleted by some 400 men,

leaving less than 1,500 of its original

3,233 troops to stand at Waterloo for

the rest of the battle.

There was a great number of

French prisoners from d'Erlon's

failed assault, perhaps more than

3,000 men. The task of escorting the

French prisoners to Brussels was

given to Bijlandt's Brigade. As a

consequence, the brigade was

further depleted by some 400 men,

leaving less than 1,500 of its original

3,233 troops to stand at Waterloo for

the rest of the battle.

Captain van Bronkhorst described what happened after the French failed assault:

"The French still maneuvered because they were the attackers. After that first attack we were spared of their assaults for approximately an hour; nevertheless we lost many men by the artillery fire and their tirailleurs who came forward in big groups. We descended into the valley, while we attacked them in our turn and drove them back. Afterward we regained our positions, because in the valley we were exposed to artillery fire. On our side, in that first attack, my Colonel M. Singendonck was wounded in his hand by a splinter of a cannonball. He handed command of the battalion over to me and withdrew to have himself bandaged. When I assumed command of the battalion, we already had a great number of soldiers and several officers killed or wounded. Up to three times I received the assignment to bring the battalion forward in order to execute the same maneuvers as I have described above. The officers excellently assisted me; more wasn't neccesary to lead the soldiers (Ons Leger, page 37).

After the failure of d'Erlon's attack, the French tried to break through the center of the Allied line by repeated cavalry charges. Around 4:00 p.m., the reassembled survivors of d'Erlon's corps again advanced on the east side of the main road to Brussels against La Haye Sainte. In order to augment the weakened front line, the 5th Militia Battalion was brought into line with the other battalions. Together, these troops were able to withstand Marcognet's infantry a second time.

An infantryman in Bijlandt's Brigade wrote of what happened next:

"we had to occupy ourselves with standing in line, where we suffered great damage, which resulted in many dead and wounded, upon which the enemy again attacked the center and hit through with the intention of dining in the evening in Brussels and to plunder, but this was bravely hindered by the reserve army, who waited there for them....

"The cavalry and Old Guard of France now pushed themselves violently onward in order to break through. The struggle was now fierce. Captain van der Bruggen was wounded in the side of his belly by a musketball that went through him and ended up in the breadbag of Pruimpje, who was standing behind him. He was carried off the field to our sorrow. He was a brave and fine man and was much loved by his men; my comrade Bindt van Oostzaan helped to carry him away. I became the first man on the right wing, first lieutenant van Zante replaced the captain, but was also hurt; he was replaced by a German, whose name I did not know. He commanded 'Close up!', but at the same time both legs were shot from under him just above the knees by a chain roundshot, upon which he collapsed and then dropped over. The same roundshot had touched my leg, but I thought not seriously, until just a little later, the blood was filling my shoe.... We carried on with our fire from two files. Our army kept closed, but we became tired, because the fighting remained hot. We were now again in the line of battle ...... (P. Wakker, pages 14-15).

The continued presence of Bijlandt's Brigade, albeit in reduced form, had not gone completely unnoticed by their allies. One British officer recalled how "a fine old Belgian colonel, having a cocked hat like the sails of a windmill, followed the movements, with his gallant little band, of our division the whole day, always in the thickest of the fire" (quoted from Andrew Uffindell and Michael Corum, On the Fields of Glory: The Battlefields of the 1815 Campaign, Greenhill, 1996, page 77).

It is amazing that these militia were still standing in line, given the mounting casualties they continued to suffer. Some companies counted less than 50% of their men still remaining. As a consequence, Colonel de Jongh reorganized the brigade. The 27th Jdger and the 7th Line were still deployed in the first line and at the same elevation as Bijleveld's battery, while the remnants of the three militia battalions were placed in second line in columns. This was the brigade's deployment for the rest of the battle. Colonel de Jongh, who had taken over command from Bijlandt, concluded:

"I have united these different troops with my battalion, placed in this way, and during the whole day, supported by English infantry commanded by Lieutenant General Picton, held this position, pushed back every enemy attack, and threw the French several times back into the valley, always making a terrible massacre among the enemy. I have sustained heavy losses in dead and wounded ...... (from the notes of Colonel de Jongh in De Nieuwe Spectator 1866, page 8).

In the evening, Napoleon made one last desperate attempt to break the Allied line with his Imperial Guard. The veteran of the 7th Militia concluded his story: "The fighting went on, but not for long; our attack was also very fierce, upon which the enemy retired and forgot to stand still, because we were so close on their heels. We pursued him day and night, this was necessary, until in France, and marched on until we halted in Paris and set up our bivouac. We looked very battered, because we had not been out of our clothes since the time of Waterloo; some of us, including me, only had half a jacket on our bodies and we looked the same as when the French sans culottes came to Holland [in 17951 and they had to be clothed there" (P. Wakker, page 15).

Bijlandt's Brigade did not take part in the general advance of the Allied troops but left the pursuit to the Prussians and set up its bivouac on the same ground where it had stood all day.

The losses of Bijlandt's Brigade were among the highest of any Allied unit. Despite the large number of "missing" soldiers, the brigade still suffered more killed and wounded as a percentage of its strength than anyone other than the King's German Legion and British troops (24% compared to 24% and 33%, respectively).

These figures were collected in the weeks after the battle, when many temporarily "missing" men were rounded up and prisoners were freed from the French, so the number of missing unfortunately must be seen as deserters. Bijlandt's Brigade was practically destroyed. A few days after Waterloo it was reorganized from five into two battalions.

The actions by at least some of the Dutch-Belgians under Bijlandt contradict many English-speaking authors' claims that his brigade fled from the field and did not participate any further. These assumptions grew from the reports published in the first edition of Captain W. Siborne's now classic reference History of the Waterloo Campaign:

"Some of these troops [Bijlandt's Dutch-Belgians] rallied and took a position farther back, but no single soldier from this unit appears to have been within musket range of French infantry all day" (pages 395-396). Siborne amended this in a later edition to excuse Bijlandt's men because of their heavy casualties, but Siborne still noted that Picton, who had only seen the Dutch- Belgians retreat at Quatre Bras, expected "but a feeble resistance on their part" at Waterloo (third edition, page 249).

Siborne's History, and numerous British memoirs which followed, influenced many more authors. Jac Weller's 1967 and 1992 editions of Wellington at Waterloo shows a typical disregard for the DutchBelgians: "But this brigade [Bijlandt] was already shaken by its none too distinguished fighting at Quatre Bras; it just did not contain the type of troops to stand a concentrated artillery fire" (page 96- 97), and, further: "the Dutch Belgian skirmisher's from Bylandt's Brigade were useless". (page 97). Weller noted that, although "Bylandt's Belgians now took themselves out of the fight....' At least, they had not deserted" (page 100).

Yes, Bijlandt's men ran. But it also also true that these militiamen poorly trained compared to the British troops adjacent to them and part of an army that had existed for less than a year, stood and suffered as many killed and wounded proportionately as any Allied brigade. They deserve a better legacy.

Andre Dellevoet is a specialist in the history of the Dutch army in the period 1795-1815 and is currently working on a book on the Dutch-Belgian cavalry in 1815.

More Cowards at Waterloo?

-

Introduction

The United Kingdom of the Netherlands Is Created

15 June: The French Advance

16 June: First Experience of Battle

17-18 June: Retreat to Waterloo and Infamy

Response to British Allegations by Renard

Combat Losses: Bijlandt and Allied (slow: 316K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #16

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Napoleon LLC.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

Order Napoleon magazine direct