The Carabiniers a Cheval comprised the two most distinctive line cavalry regiments in the French army. Immediate descendants of the elite carabiniers de Monsieur of the Royal army, the carabiniers survived the great political and military cataclysms of 1792-1800 to become a superb fighting force during the First Empire.

The Carabiniers a Cheval comprised the two most distinctive line cavalry regiments in the French army. Immediate descendants of the elite carabiniers de Monsieur of the Royal army, the carabiniers survived the great political and military cataclysms of 1792-1800 to become a superb fighting force during the First Empire.

At right, Russian shako and kiwar for the Izumsky Regiment that faced the 1st Carabiniers at Borodino.

The success of the carabiniers is partly a example of how two seemingly opposed forces at work in French society, that of the old aristocracy and the new meritocracy, could, in co-existing, actually create something both new and quite formidable. Indeed, the entire Grande Armee of Napoleon was in part blended from these forces, and credit must be given to the Emperor for his successful exploitation of both aristocratic and revolutionary traditions. Perhaps nowhere is this better illustrated than in the two regiments of Napoleon's elite carabiniers.

The French cavalry underwent a tremendous evolution in organization, composition, tactics, and battlefield employment during and following the Wars of the Revolution. Because cavalry was traditionally an aristocratic arm of service, controversy remains concerning the effects of the widespread emigration of the nobility and the various political purges upon the cavalry as a whole. David Johnson in Napoleon's Cavalry and Its Leaders states that "in regard to cavalry tactics the guillotine was more of a hindrance than an incentive". He observes that "...the French cavalry, which always attracted a higher proportion of young noblemen, lost many of its officers".

Scott Bowden, in his recent book on Austerlitz, reasons that this was not necessarily a long-term negative:

"It may appear to be a perverse sort of logic, but one positive effect the bloodletting of the Revolution had on the French military was that it finally cleansed the cavalry arm of the lazy, aristocratic officers that stifled the tactical growth and spirit of the arm, and replaced them with energetic and aggressive volunteer officers. As with any tumult, the short term effect was not good for the Republican armies. French cavalry -- always the worst arm under the Bourbons -- passed into the hands of people who, at first, had no knowledge of the trade. The result was that Revolutionary cavalry...suffered stern lessons at the hands of Allied regiments."

John Elting [our featured scholar this issue] points out that the promotions within the regiments of meritorious NCOs (the "bulwark of civilization") and impoverished nobles -- both groups previously blocked or hindered from rising during the ancien regime -- produced a gradual but ultimately impressive regeneration of the French armes blanches (literally "white weapon", referring to the sword).

The carabiniers always seem to be somewhat of an exception to any general analysis. While some officers were no doubt lost in the turmoil and chaos of the Revolution (overall, the French army lost over half of its former officer corps), the carabiniers appear to be more insulated from political meddling than other line cavalry regiments. As Elting relates, one attempt to purge the carabiniers in 1793 of an aristocratic officer resulted in a near mutiny, with the end result that the Revolutionary Representatives from Paris retreated, their uncompromising ideology evidently permitting them to occasionally back down at sword point.

The carabiniers no doubt provided a refuge for numerous aristocrats. During Robespierre's Reign of Terror, many of noble blood found the army the best place to keep their heads secure from the local Committees, so that the Terror may have had the ironic effect of actually adding aristocrats to the ranks.

The carabiniers did not emerge completely unscathed, however. In 1793 the National Assembly decreed a name change to the more egalitarian Grenadiers a Cheval. As a further affront to the carabiniers, no chin straps were issued with the grenadier-style bearskin hats they received in 1791. This omission apparently resulted in a conspicuous feature to all of their charges (until 1810) being a trail of fallen hats and a higher than expected rate of head wounds.

At the beginning of 1796, the carabiniers were two of the 20 regiments of cavalerie de bataille ("battle" or heavy cavalry); the heavy cavalry comprised nearly 40% of the 51 cavalry regiments available. During the Revolutionary Wars period, the carabiniers served at Valmy (1792), Arlon (1793), Frankenthal (1795), Mannheim (1795), and Biberach (1796).

In 1800, under the Consulate, the carabiniers served in the Armee du Rhin. Further evidence concerning the noble make-up of the carabiniers comes from this anecdote from the 1800 campaign, cited from Elting's Swords Around A Throne:

"The 1st carabiniers had one unique souvenir. During 1800 they had been billeted in the poor German town of Eichstadt, which had just been 'struck' with so heavy a contribution that its citizens would have to sell their church's sacred vessels to raise the money to meet it. The carabinier officers tried to get the contribution reduced; failing in that, they dug into their own pockets to help pay the levy. For years afterward, as wars came and went, Eichstadt celebrated an annual mass for the 1er Regiment de carabiniers a Cheval.."

Obviously, such an action sets apart the carabiniers, indicating a certain noble sentiment as well as providing evidence that the officers of the regiment were probably more wealthy than most of their counterparts.

The core of Napoleon's Grande Armee was fashioned in the six channel encampments of 1803-1805 while it waited on various schemes for the invasion of England. The famous camps such as the one at Boulogne gave the army an unprecedented opportunity to develop and evolve. The combination of a revitalized and dynamic officer corps working with a large percentage of veteran troops would yield startling results on the battlefield.

For the cavalry particularly, the weeks of training produced the ability to conduct large-scale tactical movements that would give them a significant edge over their foes. During the time of these camps, Napoleon refined the corps d'armee concept of organization which would give his army an enormous advantage over the more ad hoc columns of the Russians and Austrians. For the 1805 campaign, a special feature of the army would be the formation of a Cavalry Reserve Corps; four cavalry divisions and attached horse artillery under the command of Napoleon's flamboyant brother-in-law Marshal Murat. Here the carabiniers found their place with the other heavy line cavalry, the cuirassiers.

Heavy cavalry were differentiated from their lighter cousins, the hussars and chasseurs, in that the heavies were literally bigger men mounted on larger horses and wielding heavier sabers. The carabiniers and cuirassiers were trained foremost for shock action, in which they would use their superior discipline and imposing physical presence to over-awe and, if necessary, to literally push aside their opponents.

Additionally, for the cuirassiers, the metal breastplate was intended to impress the enemy. It was a useful piece of equipment against sword blows, pistol shots, and some musket balls (the carabiniers would receive their own special cuirass in 1810). The carabiniers, officially mounted on black horses, had a striking uniform as well; the grenadier bearskin hat added another thirteen inches to the height of each trooper.

At right, illustration of 1805 carabinier by Carl Vernet.

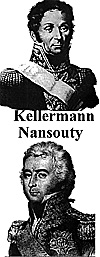

In their division commander, General Etienne Marie Antoine Champion Nansouty (1767-1815), the well-educated son of an aristocratic Bordeaux family, the carabiniers found a commander who shared similar prejudices. Nansouty managed to survive the Revolution and rose from infantry captain to eventual command of the senior cavalry division in the army. A strict disciplinarian with a meticulous eye for detail, Nansouty saw to it that the carabiniers upheld their reputation as the finest-drilled horsemen in the army. Unfortunately, Nansouty's in-bred conservatism led him to be a bit cautious on the battlefield, and thus the carabiniers, during their prime years of 1805-9, were not always led with the elan they might have deserved.

On 23 September, after the completion of the long march from France and prior to the encirclement of General Mack's Austrians at Ulm, the carabiniers numbered 478 in the 1st Regiment and 575 in the 2nd, for a total of 1,053 officers and enlisted men in six squadrons. The first battle opportunity for the carabiniers under the command of the new Emperor came on the anniversary of Napoleon's coronation, 2 December, 1805, at the battle of Austerlitz.

The key to the fighting would take place on the dominant Pratzen Heights in the center of the battlefield. Amazingly, Napoleon abandoned the position in order to intensify the notion that he was preparing to retreat. Thus, it was against these heights that Marshal Soult's 4th Corps made its celebrated attack. His forces emerged from the concealing morning mist to storm the Pratzen, momentarily undefended while the Allies chased after the "bait" (the intentionally weaker and extended French right flank).

Soult's men succeeded in breaking the Allied center, with neither Allied wing able to support the other. By order of Russian Prince Bagration, effectively commander of the Allied right flank, Austrian Prince Liechtenstein led five thousand Allied cavalry forward to attempt to halt the advance of the French left. Unused to working together, the Allied cavalry attack hit the area between the Pratzen Heights and the French left, falling upon Marshal Lannes' 5th Corps, which was supported by Murat.

At Lannes' request, Murat fed in Kellermann's Light Cavalry Division and then Sebastiani's dragoons to support the French infantry. After successes against Uvarov's brigade of Russian dragoons, Kellermann finally retired in the face of strong Russian reinforcements.

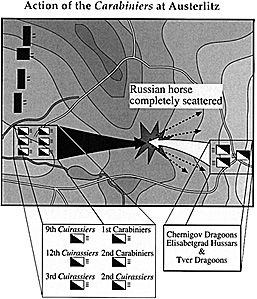

With Nansouty in the van and d'Hautpoul following, the French heavy cavalry regiments were unstoppable. The four Allied cavalry regiments facing them, namely the Tver Dragoons, Elisabetgrad Hussars, Chernigov Dragoons, and the Kharkov Dragoons, had been roughly handled in earlier cavalry encounters with Kellermann's light troops and were in no condition to oppose them.

Although Liechtenstein evidently had some fresh Austrian cavalry in reserve, they were not within supporting distance. With both regiments of the carabiniers deployed in the front wave of his division, Nansouty's men easily overcame the Russian cavalry. Scott Bowden gives this account in his Napoleon and Austerlitz:

After this success, Nansouty recalled his men behind the infantry, conducting an impressive passage of the lines. After reforming, Nansouty led his division forward again toward Uvarov's exhausted brigade. For the second time, the vaunted carabiniers found themselves in the front line of Nansouty's attack. Once again, the Russian cavalry was swept aside, only this time the Russian cavalry was shattered and spent. Based partially on the account of General d'Hautpoul's nephew, author David Johnson describes this action in sweeping terms:

"Nansouty charged again, and the whole of the Reserve cavalry flooded into movement....As the French left wing went forward, d'Hautpoul's division was joined to Nansouty's, creating one of the most impressive sights ever seen on a Napoleonic battlefield: ten regiments of heavy cavalry riding in line abreast."

Johnson says that this fight "...established the reputation of the French heavy cavalry for a decade to come". This may be a bit of an overstatement, but the action of the carabiniers at Austerlitz did maintain their high reputation. Given that the outnumbered Allied cavalry was poorly led and already fatigued by previous combats, the victory of the carabiniers and the cuirassiers was virtually assured. It would be on later battlefields that the carabiniers would prove their true mettle.

The carabiniers continued to serve under Nansouty in the campaigns of 1806 and 1807, although their opportunities for glory were few. They missed out on the decisive victory over the Prussians at Jena on 14 October, 1806. And despite the fact that Murat led one of the greatest and most desperate cavalry charges in history on 8 February, 1807, the carabiniers were fortunate to avoid the bloody stalemate at Eylau.

At Friedland (14 June, 1807) the carabiniers again played only a supporting role. General Nansouty and his division had been placed under the command of General Grouchy in Murat's absence at Kšnigsberg. The prickly Nansouty found this arrangement fairly unacceptable, and he seems to have carried out his commands with little enthusiasm. The notably caustic Grouchy ordered Nansouty to support Marshal Lannes, whose infantry, although heavily outnumbered, had been initially responsible for attacking and pinning the Russians in unfavorable terrain with their backs against the Alle River. Johnson gives a brief description of Nansouty and the carabiniers at Friedland:

"Nansouty was at his most uncooperative....On Grouchy's orders Nansouty moved his division to reinforce Marshal Lannes, who was under great pressure, but the cuirassier general was uneasy in this new position, which he thought might be out-flanked.

"Soon afterwards, returning from a charge, Grouchy was amazed and outraged to see the cuirassier regiments of Nansouty's division moving rearwards at a grand trot, leaving a dangerous gap in Lannes' battle line. Galloping after the departing cuirassiers [and carabiniers], Grouchy bellowed at Nansouty to bring them back.

"Nansouty obeyed."

Napoleon's brilliant triumph against Bennigsen's Russian army led to the Peace of Tilsit (7 and 9 July, 1807) which brought an alliance between Russia and France that lasted until 1812.

The campaign against Austria in 1809 would fully test the strength and courage of the carabiniers. While Napoleon was occupied in Spain, the Austrian war party, with English encouragement, decided that the opportunity to defeat Napoleon and regain lost territory was at hand. The main attack against the French down the Danube Valley that Spring would be conducted by the Austrian Emperor's brother, Archduke Charles. Rumored to be an effeminate francophile off the battlefield, Charles was notably courageous and inspiring under fire, at times a veritable lion. Despite being prone to occasional bouts of epilepsy, Charles was easily Austria's most able army commander.

On 17 April, the carabiniers, now consisting of four squadrons per regiment, numbered 1,721 men, 844 in the 1st Regiment and 877 in the 2nd. The 1st Cavalry Division, still under Nansouty, now numbered 5,085 men, including two batteries of six guns each of horse artillery. The new brigade commander was General Defrance.

Despite a host of delays, the Austrian offensive in the Spring of 1809 caught the French off-balance. With Napoleon absent in Paris, Marshal Berthier, an excellent administrator but not much of a independent commander, made a muddle of things for the French by not effectively concentrating the army. Unfortunately for Charles, his offensive would be compromised by the inexperience and caution of his corps commanders.

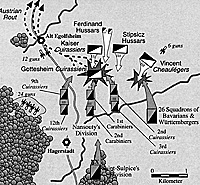

By the evening of 19 April Napoleon had arrived to take command. He placed Nansouty's heavy cavalry division under the command of Marshal Lannes. On 20 April, Lannes attacked and drove back the weak Austrian left at the battle of Abensberg. On the 21st, with Nansouty in the lead (now directly supervised by Bessieres, who had replaced Murat, now King of Naples), Napoleon and Lannes pursued the Austrians south-east toward Landshut, with its crucial crossing over the Iser River. During this pursuit, the carabiniers suffered a set-back; Bessieres ordered a suicidal charge across a canal that was easily repulsed by the Austrian rearguard.

At right, 1809 night action of Alt Egolfsheim. Sketch © Ray Rubin.

Napoleon's intention was to turn Charles' left flank. The battle of Eckmuhl went well for the French. Near the climax, Nansouty's division, after marching over 15 miles to arrive on the field, participated in a successful charge spearheaded by the cuirassiers, in which the carabiniers appear only to have lent a supporting role. Acting in their classic role, the heavy cavalry broke the Austrian center and sealed the victory.

With the Austrians defeated and in full retreat from Eckmuhl, an aggressive pursuit began. This set the stage for one of the more dramatic, if lesser known, cavalry actions of the Napoleonic Wars at Alt Egolfsheim. Here the heavy cavalry of the two armies, both supported on the flanks by light cavalry, collided in a moonlit action. James Arnold describes the fight in Crisis on the Danube:

'The Austrian troopers, many mounted on poorly trained horses, nervously strove to maintain formation as they spurred their chargers forward. The Gottesheims [the lead Austrian Cuirassier regiment] drew within a hundred yards, not failing to notice that the more numerous French overlapped their line on both flanks. Steeped in a long tradition of mounted-fire action [or, perhaps, conserving their horses after an exhausting day], the opposing French center regiment of carabiniers aimed their carbines. At forty paces they fired a volley into the faces of the charging Hapsburg troopers.

Each side added forces to the initial melee. An Austrian attempt to outflank Nansouty was checked by supporting Bavarian cavalry. Finally, the Austrian cavalry broke, and chaos prevailed as they fled in the darkness down the Ratisbonne road. The exhausted French were satisfied to halt after a short pursuit.

On the following day, the carabiniers took part in the general rush to Ratisbonne. Here again Nansouty's habitual caution, coupled with the overall fatigue of his command, prevented his division from seizing one of the pontoon bridges that Charles was using to retreat across the Danube. It was a minor failure that went unnoticed in the swell of larger events.

The opening phase of the 1809 campaign, which had begun with so much promise for the Austrians, ended with the French pushing Charles out of Ratisbonne and across the Danube. The next phase of the campaign would begin in earnest after the fall of Vienna, with Charles reorganizing his defense on the far bank of the Danube. Napoleon would have to accomplish one of the meaner feats of war: crossing a major river against a determined enemy.

By 15 May, less than a month since the start of Napoleon's counter-offensive, the carabiniers were down to 551 men in the 1st Regiment and 585 men in the 2nd, an overall loss of 34% of their effectives. This is a significant loss of strength, averaging over 1% per day (including some battle losses), rather remarkable considering the elite status of the carabiniers. These figures suggest severe fighting and an exacting pursuit of the Austrians to Vienna.

Anxious to put an end to the 1809 campaign, Napoleon made preparations to cross the Danube and destroy Charles' force. Using Lobau Island, directly across from Vienna, as the first stage of its crossing, the French army made a bridgehead across the Danube anchored upon the towns of Aspern (on the French left) and Essling (on the right).

Charles had made preparations of his own. Having allowed a portion of the French army to cross, he planned a full-scale assault designed to throw the outnumbered French into the Danube. As part of his scheme, the Austrians prepared large barges that would float down the river and cut the French bridges to Vienna, thereby isolating the French bridgehead from reinforcement and supply. The result was the two-day battle of Aspern-Essling (21-22 May, 1809), one of Napoleon's most desperate battles and the first defeat suffered by his Grande Armee.

On the afternoon of the 21st, Charles attacked with over 100,000 men. Desperately outnumbered, Marshal Massena held the French left and Marshal Lannes held the right. The unenviable job of defense of the vulnerable French center fell on General d'Espagne's cuirassier division. Forced to make repeated forlorn charges just to stall the Austrians, the cuirassiers suffered greatly, losing about one-third of their effectives.

The grim fighting finally ended at nightfall, when Nansouty's mounted troopers rode across in preparation for action on the 22nd. Napoleon optimistically believed he could break the Austrian center the next day. It would prove to be a serious miscalculation.

Spearheaded by Marshal Lannes, Napoleon's morning assault made headway but did not rupture the Austrian lines. At a critical point, around 8 a.m., Napoleon received alarming news that the Danube bridges had been broken. Without further possibility of reinforcement and resupply, Napoleon ordered the attack to halt. Lannes, along with Nansouty's heavy cavalry division, executed a skillful withdrawal back to the defensive perimeter of the previous day.

For the remainder of the 22nd, the former artillery captain and his men would suffer a horrible bombardment from the well-served Austrian cannons. A lesser host might have dissolved, but the majority of the Grande Armee, inspired by the stoic and stalwart behavior of many of its officers and veterans, closed ranks and hung on.

During this phase of the battle, the carabiniers suffered terribly. Exhausted from their earlier charges, the cavalrymen were forced to stand and endure periods of intense enemy artillery fire. The carabiniers were withdrawn late in the day as the Imperial Guard came up to cover the middle of Napoleon's crumbling army, now desperately holding on to portions of Aspern and Essling.

France's Grand Army suffered one of its greatest individual losses this day. Marshal Lannes, perhaps Napoleon's closest friend, was mortally wounded by a cannonball. Evidently, Lannes was borne back to the Emperor by members of the carabiniers, who carried him in a blanket, and these men witnessed Napoleon's emotional farewell to his favorite Marshal.

That night, with the bridge repaired, Napoleon retreated for the first time since he had fought in Italy twelve years earlier. Over the next several weeks, the Grande Armee regrouped and received reinforcements. During this time, Nansouty first requested that consideration be given to equipping the carabiniers with the metal cuirass. Perhaps recognizing the potential negative effect that turning the famed carabiniers into "mere" cuirassiers might have on their morale, according to David Johnson, the Emperor instead chastised Nansouty for always leading with the carabiniers, and not allowing the cuirassiers regiments to take their proper turn in the rotation. Ultimately, however, the germ had been planted for the dramatic uniform change that would take place the following year.

Napoleon's second crossing of the Danube was much better prepared than the first. The bridges were secure and extensive, and Lobau Island was well-fortified. The carabiniers had been reinforced to a strength of 663 for the 1st, and 701 for the 2nd Regiment, for a total of 1,364 men in eight squadrons. On 5 July, the Grande Armee crossed from Lobau Island to the Marchfeld, marching past the site of the previous battlefield.

Charles formed his lines further back, primarily along the Russbach Heights, a low rise situated behind a steep-banked stream that offered excellent artillery positions. Late in the day, Napoleon launched an assault on the Austrian center and left in hopes of taking the key villages of Wagram, Baumersdorf, and Markgrafneusiedl; this marked the beginning of the great two day battle of Wagram that would involve about 300,000 men and nearly 1,000 artillery pieces (easily eclipsing in size more famous battles such as Waterloo, Austerlitz, and Borodino).

These twilight attacks achieved limited initial success but at a high price in losses, and the first day's fighting ended with a resounding French repulse. On 6 July, Napoleon planned to resume his offensive of the previous evening. However, Charles had planned an offensive of his own, a grandiose double-envelopment intended to cut the French off from their Danube bridges. This maneuver surprised the French and achieved early success.

In the center of the French lines, the Austrians took the key village of Aderklaa, abandoned and unoccupied by the insubordinate Marshal Bernadotte for reasons that remain murky. Furious, Napoleon ordered Massena and Bernadotte to re-take it. Meanwhile, on the French left, the Austrians advanced against light opposition toward Aspern and the Lobau bridgehead deep in the French rear. Only General Reynier's 100 gun grand-battery on Lobau checked this threat.

Further intensifying the sense of disaster, Bernadotte's Saxon infantry, roughly handled the previous day, broke and ran from an Austrian cavalry attack. Only the superb Saxon cavalry saved them from a merciless sabering. The situation worsened when the French were forced out of Aderklaa. At the height of this crisis, the moment had arrived for Napoleon and the carabiniers to retrieve the situation.

Despite having nearly everything go wrong from the outset on 6 July, Napoleon, with typical sang froid despite being under heavy fire several times, remained measured. The Austrian success had been achieved at the cost of committing nearly all of their reserves. With the French army concentrated in the center, and with the majority of it as yet uncommitted, a victory could still be won if the situation were stabilized. Accordingly, Napoleon made the following bold move: Massena's men would be pulled from line of battle and marched to the French left to finally check any Austrian threat to the army's lifeline at Lobau. Then Davout's 3rd Corps would deliver the fatal blow against the Austrian left.

Pulling Massena's men out of their positions would create a gap in the French center. To fill that hole, Napoleon ordered Bessieres cavalry reserve forward; he in turn selected Nansouty and his division to lead the way. As at Aspern-Essling 45 days earlier, heavy cavalry would be sacrificed to buy time.

As usual, Nansouty appears to have relied primarily on the carabiniers, who found a seam between two Austrian corps -- Kollowrath's 3rd and Liechtenstein's Reserve Corps -- and pressed home. Of Nansouty's three brigades, Defrance's carabiniers were the only ones that closed decisively with the enemy, and Nansouty failed to support them. The carabiniers overran a Grenz (Slavic light infantry) regiment from Kollowrath's corps, but ran into Liechtenstein's stubborn grenadiers, who did not break.

Liechtenstein's artillery shredded the carabiniers: Author James Arnold quotes one participant who claimed that only "one in five men managed to penetrate this barrage...." Nansouty attempted to wheel Defrance's men in such a manner as to flank and overrun the majority of Liechtenstein's artillery. It was a bold if desperate maneuver, but before it could be pressed home, Austrian cavalry in turn flanked and pushed the carabiniers back toward French lines. General Defrance had two horses killed from underneath him, the second throwing him so severely that he was borne by the carabiniers from the field, and his sword received a direct cannon ball hit that twisted it into the shape of a corkscrew.

Although a tactical failure, Nansouty's hopeless, heroic charge bought Napoleon the time he needed. It also marked the turning point in the battle. The hour dearly purchased enabled the Grande Armee to change over to the offensive and seize the overall initiative. But the cost was high again: Nansouty's division lost about 500 men and 1,150 horses. According to Arnold: "In the carabinier brigade, fewer than 300 horses remained standing by day's end, an equine loss rate of 77%." In addition, Marshal Bessieres was seriously wounded early in the attack; his absence was cited as a main cause of the cavalry's failures.

Eventually, Davout's flanking assault, coupled with Marshal Macdonald's dramatic attack in the center late in the battle, turned near defeat into victory once again. But Wagram was the last decisive victory that led directly to a favorable peace for the French Emperor.

Perhaps one last statistic speaks volumes about the caliber of the carabiniers during this period. In all the battles of 1806, 1807, and 1809, the 2nd Carabinier Regiment did not lose a single man as a prisoner of war.

More Carabiniers

The Carabiniers Survive the Revolution

"The French cavalry, on the whole, had been damnably misused through the Revolutionary Wars...."

Part of a New Kind of Army

Leading the Heavy Cavalry

at Austerlitz

When Austria declared war late in 1805, the carabiniers were in General Piston's 1st Brigade of General Nansouty's 1st Heavy Cavalry Division of Murat's Cavalry Reserve Corps. These designations clearly indicate that the carabiniers were the senior line cavalry regiments of the army.

When Austria declared war late in 1805, the carabiniers were in General Piston's 1st Brigade of General Nansouty's 1st Heavy Cavalry Division of Murat's Cavalry Reserve Corps. These designations clearly indicate that the carabiniers were the senior line cavalry regiments of the army.

The carabiniers entered the fight when Murat played his trump card: the ten heavy cavalry regiments of Nansouty's 1st and d'Hautpoul's 2nd Heavy Cavalry Divisions. A little more than two months after they rode out of France, the carabiniers were down to only 205 men in the 1st Regiment, or 43% of their strength at the beginning of the campaign, and the 2nd Regiment had 181 men, or 31% of their original numbers. The strategic consumption for the carabiniers over the course of the 1805 campaign had been staggering, and it underscores the fact that Napoleon's army had suffered greatly, and desperately needed a decisive victory.

The carabiniers entered the fight when Murat played his trump card: the ten heavy cavalry regiments of Nansouty's 1st and d'Hautpoul's 2nd Heavy Cavalry Divisions. A little more than two months after they rode out of France, the carabiniers were down to only 205 men in the 1st Regiment, or 43% of their strength at the beginning of the campaign, and the 2nd Regiment had 181 men, or 31% of their original numbers. The strategic consumption for the carabiniers over the course of the 1805 campaign had been staggering, and it underscores the fact that Napoleon's army had suffered greatly, and desperately needed a decisive victory.

"The Tver Dragoons crumbled immediately in front of the charge of the carabiniers. By the time Uvarov arrived on the scene with the Elisabetgrad Hussars and the Chernigov Dragoons, the carabiniers had wheeled in a southeasterly direction to meet them. Although outnumbered approximately three to one, the unarmored carabiniers crashed into the Russian horse and were holding their own when Nansouty fed into the melee the 2nd and 3rd Cuirassiers. These 596 armored horsemen thundered forward and overthrew the Chernigov Dragoons as well as a portion of the Elisabetgrad Hussars."

"The Tver Dragoons crumbled immediately in front of the charge of the carabiniers. By the time Uvarov arrived on the scene with the Elisabetgrad Hussars and the Chernigov Dragoons, the carabiniers had wheeled in a southeasterly direction to meet them. Although outnumbered approximately three to one, the unarmored carabiniers crashed into the Russian horse and were holding their own when Nansouty fed into the melee the 2nd and 3rd Cuirassiers. These 596 armored horsemen thundered forward and overthrew the Chernigov Dragoons as well as a portion of the Elisabetgrad Hussars."

Little Action in 1806-1807

First Real Test in 1809

The carabiniers' first opportunity for a major action came at the battle of Eckmuhl and its aftermath on 22 April. Prior to this, the carabiniers had been accorded the honor of providing the Emperor's escort, as the Imperial Guard cavalry had not yet arrived from Spain.

The carabiniers' first opportunity for a major action came at the battle of Eckmuhl and its aftermath on 22 April. Prior to this, the carabiniers had been accorded the honor of providing the Emperor's escort, as the Imperial Guard cavalry had not yet arrived from Spain.

Replacing their firearms, the carabiniers drew swords and charged. Simultaneously, the order rang out to the French cuirassiers on either flank....The French line advanced. The physical pressure exerted by troopers riding knee-to-knee on giant Flemish and Norman horses ensured a proper alignment. The biggest troopers rode in the center. Only their superior strength, aided by high stiff riding boots, kept them from being squeezed out of the formation."

Replacing their firearms, the carabiniers drew swords and charged. Simultaneously, the order rang out to the French cuirassiers on either flank....The French line advanced. The physical pressure exerted by troopers riding knee-to-knee on giant Flemish and Norman horses ensured a proper alignment. The biggest troopers rode in the center. Only their superior strength, aided by high stiff riding boots, kept them from being squeezed out of the formation."

Holding the Center at Aspern-Essling

Buying Time at Wagram

Carabiniers Section 1: 1679-1791

Carabiniers Section 2: 1792-1811

Carabiniers Section 3: 1812 and After

Carabiniers Uniforms 1801-09, 1810-15

Carabiniers Uniform Colors 1788-1815 (slow: 114K)

Carabiniers Postings: 1792-1815

Issue Cover: Carabiniers at Borodino (very slow: 224K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #10

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Emperor's Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com