Most readers will be familiar with First Bull Run as the opening battle of the American Civil War. There were skirmishes before, of course, but the results of Bull Run set the stage for the next several years. After the various southern states declared independence and formed their own confederacy, both sides raised bodies of short-term volunteer militia to contend over the constitutionality of secession. These armies were largely made up of volunteer companies assembled into regiments and hastily thrown together into brigades and higher organizations. These volunteers were young, eager, inexperienced, and inadequately trained. Their officers were somewhat better. Gentlemen with military training, education, or experience in the war with Mexico were promoted several steps above the rank at which they had last performed. Weapons and equipment were hauled out of state and federal armories and varied widely in quality.

Most readers will be familiar with First Bull Run as the opening battle of the American Civil War. There were skirmishes before, of course, but the results of Bull Run set the stage for the next several years. After the various southern states declared independence and formed their own confederacy, both sides raised bodies of short-term volunteer militia to contend over the constitutionality of secession. These armies were largely made up of volunteer companies assembled into regiments and hastily thrown together into brigades and higher organizations. These volunteers were young, eager, inexperienced, and inadequately trained. Their officers were somewhat better. Gentlemen with military training, education, or experience in the war with Mexico were promoted several steps above the rank at which they had last performed. Weapons and equipment were hauled out of state and federal armories and varied widely in quality.

These hastily raised units found there way to Virginia, and Washington DC to prepare for the coming conflict. There was little time for regimental, brigade, and division commanders to learn to know and trust one another. Regimental and company commanders were busy just learning how to feed their soldiers, cope with outbreaks of disease, and learn their trade themselves. Getting six hundred men to move and change direction and formation in unison on an open field is hard enough. Moving a double rank of soldiers across broken ground to start volley fire amid the noise, smoke, and palpable fear is quite another. Getting these six hundred rookies to charge into a hail of bullets and close with the enemy and kill them with the bayonet is extraordinarily difficult. In the actual battle, many units would fail and others would shine.

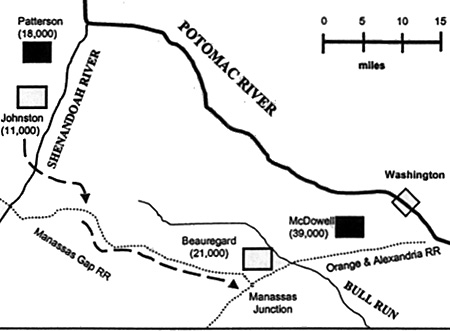

As the forces assembled, the Union kept the bulk of its forces, about 39,000, under Irvin McDowell in the vicinity of Washington to protect the capital as they trained. A smaller force under Robert Patterson was stationed at Harpers Ferry. Opposite Patterson and guarding the Shenandoah Valley was Joseph E. Johnston who had about 11,000 troops to Patterson's 18,000. Pierre G.T. Beauregard commanded the largest confederate force, about 21,000, at Manassas Junction. Manassas was along the major route between Washington and Richmond and was at the juncture of two rail lines, one of which extended westward to link Johnston's force with Beauregard's. The confederates organized their forces into brigades, while the union assembled brigades into divisions. This gave McDowell an easier span of control, as he had fewer people to communicate with in order to control his army.

McDowell tried to delay his move until his army was properly organized and received sufficient training. However, the powers in Washington prodded him to a premature start. On 16 July McDowell's army lurched forward. The troops were so poorly conditioned physically that movement was slow and hundreds of rookie soldiers fell out due to the severe heat. The confederates picked up on the federal move very quickly and Beauregard began drawing his forces in closer together and behind Bull Run. In Richmond, Jefferson Davis ordered other units to report to Beauregard and on 18 July, Johnston received an order to join his colleague "if practicable." In a bold move, Johnston decided to accept a serious risk. He left a small element in contact with Patterson to deceive the union commander of Johnston's intentions. He then led his five brigades south where they picked up the rail line and moved toward Manassas Junction.

McDowell tried to delay his move until his army was properly organized and received sufficient training. However, the powers in Washington prodded him to a premature start. On 16 July McDowell's army lurched forward. The troops were so poorly conditioned physically that movement was slow and hundreds of rookie soldiers fell out due to the severe heat. The confederates picked up on the federal move very quickly and Beauregard began drawing his forces in closer together and behind Bull Run. In Richmond, Jefferson Davis ordered other units to report to Beauregard and on 18 July, Johnston received an order to join his colleague "if practicable." In a bold move, Johnston decided to accept a serious risk. He left a small element in contact with Patterson to deceive the union commander of Johnston's intentions. He then led his five brigades south where they picked up the rail line and moved toward Manassas Junction.

The capacity of the rail lines was limited and Johnston's men were shuttled forward. However, Johnston himself arrived at Manassas Junction on 20 July and he assumed command of the combined force. It was soon enough. McDowell's slow advance had forfeited all possibility of surprising the confederates. Nonetheless, the union commander made a cursory reconnaissance of the area and concocted a fairly adroit plan to turn the confederates out of their relatively protected position. If all went according to plan, McDowell would soon be in Richmond and crush the rebellion.

McDowell had organized his force, the Army of Northeastern Virginia, into five divisions. He had kept Runyon's troops near Alexandria to continue organizing. With four divisions at Centreville, about three miles from Bull Run, McDowell had the combat power to defeat the confederates.

While Johnston's confederates were still moving by rail to Manassas Junction, the total organization looked like the chart below. Note that Beauregard's force was named the Army of the Potomac. Both the union and confederate forces had their share of graduates from the military academy at West Point, although many of these well educated soldiers had not commanded forces larger than a battalion.

Going It Alone: The Solo Wargamers Corner First Bull Run (part I):

-

Introduction

The Preliminaries

Orders of Battle: USA and CSA

The Battle

Solo Rules

Cohesion, Command, and Control

Going It Alone: The Solo Wargamers Corner First Bull Run (part II):

Back to MWAN # 121 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com