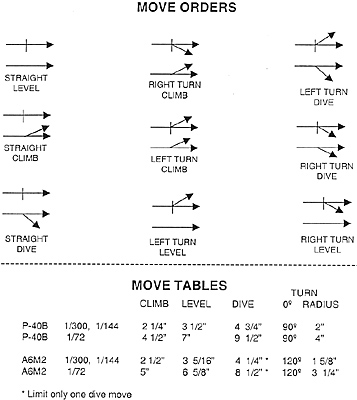

Players place their planes on the gaming surface and indicate height. Usually the two planes are facing each other about two moves apart at the same altitude. A game cycle takes three steps: writing orders, moving, and firing. The game moves fast. Usually it’s over in fifteen minutes. Writing orders takes just seconds. Each player draws the diagram for the maneuver he wants his plane to do. See the illustration labeled “orders.”

Players place their planes on the gaming surface and indicate height. Usually the two planes are facing each other about two moves apart at the same altitude. A game cycle takes three steps: writing orders, moving, and firing. The game moves fast. Usually it’s over in fifteen minutes. Writing orders takes just seconds. Each player draws the diagram for the maneuver he wants his plane to do. See the illustration labeled “orders.”

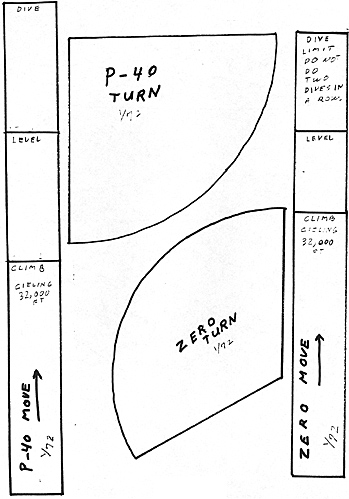

Then on to the moves. Each player moves his plane according to the orders. Use the movement templates. If the plane is diving straight ahead, use the straight move template and move the plane the distance on it marked “dive.” If turning, place the turning template so the plane is tangent to the curve and slide the plane along the curve. If the plane dives or climbs, the player must indicate this. A dive or climb changes altitude by 5000 feet. We have used two methods of showing altitude. Put the plane on Legos stacked one per 5000 feet or simply put a paper note of the altitude next to the plane. Note that the Zero cannot do two dives in succession. As much as practical, both players should move simultaneously. As you move, notice if the other plane crosses your line of fire.

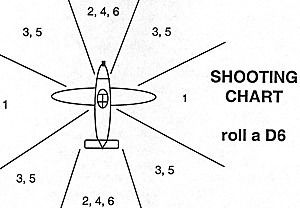

Each plane flies straight ahead for a range equal to one level move. If at any time the enemy plane crosses the line of fire, there is a shot. Roll 1D6 and see table for hits. In general, deflection shots at a crossing target are harder than head-on or tail shots. Both planes use the same hit numbers, but the Zero must hit the P-40 twice for a kill while the P-40 shoots down the Zero with one hit.

See the shooting diagram. If both planes are still flying, repeat the cycle: write orders, move, and shoot. The whole process takes less than a minute.

See the shooting diagram. If both planes are still flying, repeat the cycle: write orders, move, and shoot. The whole process takes less than a minute.

I have provided models of a P-40 and a Zero in roughly 1/72 scale. By the time they are in print, the scale will be changed. My movement templates are also for 1/72 scale. I have provided an inch measure to show the change in size and listed the measurements in the table. I usually play this game in 1/300 scale with lead planes. I cast these myself. I have also used some 1/50 scale card stock models. The Flying Tigers flew the P-40B. These planes were originally intended for Sweden. So why are they painted standard Royal Air Force sand and spinach camouflage? These planes are part of the Chinese Air Force, so they wear the Nationalist Chinese sun. This is a white circle, a blue ring, and white rays against a blue circular background. Most of them will have a shark’s mouth and eye painted on their nose. The yellow and black flying tiger is on their fuselage. His wings are blue.

There were three squadrons: Adam and Eves (First Pursuit), Panda Bears (2nd), and Hell’s Angels (3rd). Adam and Eves used as squadron insignia an apple with figures of Eve chasing Adam with a snake around the apple. The apple was light green, Eve pink, Adam khaki, and the snake dark green. They had a white band around their fuselage. The Second Squadron used a black and white panda bear. Not all planes had these because the artist was killed in action before he could do them. They had a blue fuselage band. The Third Pursuit had pictures of curvaceous women done in red with halos and white wings. Their fuselage band was red.

There were three squadrons: Adam and Eves (First Pursuit), Panda Bears (2nd), and Hell’s Angels (3rd). Adam and Eves used as squadron insignia an apple with figures of Eve chasing Adam with a snake around the apple. The apple was light green, Eve pink, Adam khaki, and the snake dark green. They had a white band around their fuselage. The Second Squadron used a black and white panda bear. Not all planes had these because the artist was killed in action before he could do them. They had a blue fuselage band. The Third Pursuit had pictures of curvaceous women done in red with halos and white wings. Their fuselage band was red.

The Zero shown is actually in Pearl Harbor paint job. The engine cowl is black. Most of the plane is light gray. The national insignia is a round red rising sun. The stripes are red.

Now let’s consider a solo game. Assume you are flying the P-40. Set up the planes facing at 15000 feet. Each plane is balanced on three Legos. The process is the same as the basic game except for orders. Write your orders for the P-40. Dice for the orders of the Zero. Using 1D6 first roll for direction: 1, 2 = right turn; 3, 4 = straight, 5, 6 = left turn. Then roll for elevation: 1, 2 = climb; 3, 4 = level; 5, 6 = dive. Notice that a Zero cannot dive in two consecutive turns. After this, do moves and shots just as in the two-person game.

For added spice, roll a third time during the Zero orders rolls. If that turns up a 6, you have a second Zero on your tail! You could also elect to fight an aggressive Zero pilot. His orders would be: always turn toward the enemy. Favor left turns. Keep the rule about a 6 meaning a second Zero on your tail.

The solo version can be a fairly interesting variation. I find that it depends on my mood. Sometimes I can make the enemy plane feel real and sometimes it’s just a random act of die rolls. It all depends on your imagination.

Campaign Game

The campaign game so far only exists in my imagination. I have thought about it and gathered some supplies for it, but have yet to play it. Actually there are, or could be, two versions.

The first version I thought of was a big scale campaign game played on a large surface. My first thought was to chalk a map of Burma and other areas on my concrete driveway. I could mark the airports and establish planes at those bases. Presumably this would be an open game, that is, each player could see the other’s planes. A standard move would be one foot for each hundred miles per hour. The map would probably be on a scale of one foot equals 100 miles. Since the basic combat game in 1/300 scale is one inch for each hundred miles per hour, the ratio of combat moves to long range moves would be 12 to 1. Twelve moves in a dogfight equals one on the board. Assuming a twelve hour day, there would be twelve turns for big moves.

If a dogfight developed, each side should make the next hour’s move; then fight the dogfight for twelve turns. By this device, the two commanders would be unable to adjust moves to reflect the outcome of a dogfight which in a real situation they could not predict. The two commanders should also be required to mark campaign moves on a rough map before they make them on the playing surface. Thus they do not adjust their moves to meet enemy moves they could not realistically know about.

In a campaign game, range would become a factor. No plane could fly farther than its gasoline would allow. Refueling also becomes a problem. About an hour should be required for a refuel, rearm, and general servicing stop. At that stage a plane would be particularly vulnerable. Repair of damaged planes could also be a factor as would pilot survival. If a plane was shot down, a die roll should decide if the pilot survives. Roll a 3 or higher, and the pilot is alive. The plane may be damaged to a greater or lesser degree. The first consideration would be where it came down. If it lands in enemy territory, forget it. Any surviving pilot down in enemy territory would be considered a prisoner. Planes that come down over water are also lost. The pilot has a good chance of surviving. Roll a three or higher on a die, to be either captured or picked up by friends, depending on who controls the water. The question of who controls what land or water should be determined by reference to the position of historical forces on the day the campaign starts.

Assuming that the plane came down in friendly territory, the question of the extent of the damage can be resolved by a die roll. A P-40 is a sturdy plane; its chances of repair are much higher than Japanese planes. I would suggest the following table.

- 1: plane can be repaired and ready for action the following morning.

2-3: plane can be repaired and ready for action in 24 hours

4-5: plane can be repaired in 24 hours if there are parts available from another plane

6: plane cannot be repaired but may be salvaged for spare parts.

The table for a Zero and other Japanese types would be more like this:

- 1: plane can be repaired and ready for action the following morning

2: plane can be repaired and ready for action in 24 hours

3: plane can be repaired in 24 hours if there are parts available from another plane

4-6: plane cannot be repaired but may be salvaged for spare parts.

These tables could also be used to evaluate damage done to planes by bombing or strafing. Strafing has a good chance of hitting planes on the ground. Roll a 3 or higher for each pass for a hit. But since damage from strafing is less serious, subtract two from the roll for damage [see the tables above]. Bombing has a poorer chance for a hit so roll a 5 or 6 for a hit from a bomb. Since bomb damage is more serious than strafing damage, add two to the damage roll.

In all cases where planes have to be transported to a field or pilots return, simply measure the distance, one foot equals 100 miles per hour remember. Then figure the speed, walking 4 mph, jeep 30 mph, etc. This should give you the time required for the pilot or plane to return to action.

While it would be possible to fight a campaign on a one to one scale for planes, it would be a bit large. The Flying Tigers had only 15 planes at Rangoon. Some Japanese raids consisted of 27 planes. Perhaps a scale of one model equals 3 planes or 5 would be more manageable. If you really want to scale down, one plane could equal one squadron.

Playing out the campaign would probably require a campaign clock set to show the time of day. Perhaps you could find an old clock that has died? Also a calendar would be helpful to keep track of the days. The Flying Tigers were only in action from December, 1941 to July 4, 1942. A game could run any length of time, from one day to the entire period of action.

There are a number of practical reasons why playing a campaign on the driveway may not work. People have a way of driving cars on driveways. This could be catastrophic if the surface is covered with planes. The alternative would be to use a map of the area and move either pins or planes as markers to show campaign moves. Dogfights could then be fought on a separate table. The move would have to match the scale of the map, one hour’s move equals the number of miles the plane would move. There is a nice outline map of Southeast Asia available from the Defense Mapping Agency.

History of the Game

As a history teacher I often used political simulations. I was curious about military simulation but could find nothing specific. Then I spotted Peter Young’s The War Game for sale. Using the bibliography and writing letters I was soon reading H.G. Well’s Little Wars and looking at catalogs of model soldiers. In general this started a process of getting involved in war gaming. My two sons took to gaming and we were off.

One day in the 1970s, I got the flu and had to stay home from work. My son, Paul, was doing a research paper on the World War II North African campaign and had several books at home. They were all I had to read. So, combine recent reading of Little Wars, some junior high level histories of North Africa and a sick mind and what do you get? The result was a game called “North Africa.” It was extremely simple, using generic tanks which were cardboard silhouettes. The boys and I played it a lot over the next year. We worked out a set of scenarios and expanded some of the rules. After a year of playing at home, it dawned on me that this game was simple enough to use at school. Soon after, my world history classes were playing it as part of the World War II unit of instruction. This went on for over twenty years. I eventually wrote up the North Africa Game and sold it as a chapter in my book Games for Teaching World History.

Meanwhile, the aerial part of North Africa was developing. At first an air strike was symbolized as a die roll. Roll a 4 or 6 and the target was destroyed. Later we added an optional rule about sending out fighters to shoot down the attacking dive bombers. So far this was all strictly die rolling, no models. But somewhere along the line models got involved and the subject changed a bit.

I found a history of the Flying Tigers and I read a book about the P-38 fighter. The P-38 book showed a reenactment of an air battle using models. Somehow mixing that with North Africa produced the basic game of Flying Tigers. The models were roughly 1/144 scale and made of cardboard. In World War II in the U.S. there had been lots of paper or cardboard models of airplanes. They were available for a cereal boxtop and a quarter, or in some cases the models were just printed on cereal boxes. As a kid in that time I quickly learned how to make my own designs. As I used that ability in the 1970s I was delighted to find that study of World War II aircraft and modeling them was a respectable adult hobby. How nice to find I wasn’t just being immature.

The game has proved to be endlessly fascinating. It is very easy to learn and uses a lot of playing aids, so it moves very quickly. I improved the models. I changed to 1/300 scale planes cast in lead, building my own originals using plaster molds. At the time some wargames books gave instructions for doing such casting. The basic simultaneous move system, turn and move templates, and firing rules have remained the same. Over the years I have applied the basic system to the Korean War and World War I, but the heart of the game has remained World War II air combat U.S. vs. Japan. We still play the basic game in my family. In fact my grandson, Peter, plays it with me sometimes. That makes three generations.

At one time I had a plan to revise it. I would survey the world of games and learn all the best rules etc. and produce the ultimate air combat game. I surveyed naval warfare from the 1790s (that’s not a misprint) and land wargames from the 1820s and even early air wargames from 1912. I read books and magazines and even joined something called the Solo Wargamers Association. But recently I decided that revising Flying Tigers was not in the picture.

In researching naval wargames I read a book by an admiral on how to plan a battle. He made the point that often the perfect plan was the enemy of the “good enough” plan. It seems that by trying to be perfect, planners often messed up an imperfect but good enough plan. For me the Flying Tigers is good enough.

Note: This game system is also used in The Korean War: Mig Alley in Lone Warrior 127 (North American edition). That version includes a postal system and some variations on a solo opponent.

Note on Names:

I have used names current in 1941-42. Since then, much has changed. Burma is now Myanmar and Rangoon is now Yangon. Chiang Kai-shek is Jian Jieshi. There are probably other changes as well. As usual, there is the fact that I write in the U.S.A. and many readers are in the United Kingdom. As Kenn Hart recently reminded me, that creates a language barrier. I will ignore my wife’s comments on my creative spelling.

The P-40 illustrations are based on two magazine articles and pictures on their covers:

- “Lowing Fighter Duel” by Daniel Ford, Aviation, July, 1993.

“Robert Scott - God Was His Co-Pilot”, by James H. Cockfield, World War II, January 1996.

More Flying Tigers

- Historical Background

Air Combat Tactics

Wargame Rules

Robert L. Scott: Historical Campaign

Model Templates

Back to Table of Contents -- Lone Warrior #136

Back to Lone Warrior List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Solo Wargamers Association.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com