Listen up, pilgrim. This is about a colorful story set in Asia during World War II. It’s part history, part legend, and almighty interesting. There is a John Wayne movie about it and also a ton of books. Back in the old days, I designed a game based on the legend. Three generations of my family have played the game. It became the basis for my Korean War MIG Alley game and even a World War I game, but for now, let’s stick to World War II. First comes the story, then the game including rules, models, solo systems, and campaign ideas. It’s all here, so even a tenderfoot can handle it.

Listen up, pilgrim. This is about a colorful story set in Asia during World War II. It’s part history, part legend, and almighty interesting. There is a John Wayne movie about it and also a ton of books. Back in the old days, I designed a game based on the legend. Three generations of my family have played the game. It became the basis for my Korean War MIG Alley game and even a World War I game, but for now, let’s stick to World War II. First comes the story, then the game including rules, models, solo systems, and campaign ideas. It’s all here, so even a tenderfoot can handle it.

The story of the Flying Tigers starts in China in the 1930s. So far as most westerners were concerned, the Government of China was run by the Nationalist Party led by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Only the real China experts knew about the communist revolutionaries living far back in the hills. Chiang had lots of problems. He was trying to hold together a shaky coalition of warlords, businessmen, idealists and landowners. At the same time he had to fight a war defending China against Japan. In 1931, Japan had taken Manchuria. A few years later Japan invaded the rest of China.

Even then Japan was a modern industrial country. Her armed forces had modern ships, tanks, and aircraft. China was a poor country but a big one. The Japanese were relatively easily able to conquer the rich grain producing regions of China and the relatively modern cities along the coast. Chiang moved his government deep into the interior and held on. He tried to get outside aid, but it was never really enough.

Chiang wanted an air force to counter the Japanese planes that were blasting China’s cities at will. First he hired Italians to train his Chinese pilots. After a time it became clear that the Italians were incompetent. They were fired. Next, he appealed to the Soviet Union. The Generalissimo had himself been trained in Moscow in the 1920s. The Soviet dictator, Stalin, sent planes and pilots. The Russian pilots were strictly disciplined and their planes were about a match for the Japanese. Unfortunately, Germany was threatening the Soviet Union in Europe, so the planes and pilots were needed elsewhere. Once again China lost its foreign air force.

But there was a ray of hope. Chiang Kai-shek had hired a retired U.S. Army Air Corps pilot named Claire Chennault to serve as his advisor. Chennault was to train Chinese pilots to fly American planes purchased on the open market. In 1938-39, China bought a squadron of P-36Ms, a fixed landing gear version of the U.S. army fighter. Chennault was a type Americans often admire, a rebel. The U.S. Army Air Corps was full of rebels who resented the resistance of old-fashioned infantry generals who did not realize that air power would win the next war.

Unfortunately, Chennault disagreed with them. He did not believe that the bomber could always get through and deliver blows that would win the war. Instead, he argued, very publicly and in print that planes properly used could stop bombers. He had studied some RAF exercises in the early thirties. He concluded that, given a network of observers to report the location etc. of attacking bombers, pursuit planes could intercept the bombers and shoot them down. His advocacy of these ideas meant he had little future in the U.S. Army Air Corps. But he seemed to fit like a glove as Chiang’s air advisor.

Partly this was because of Madame Chiang Kai-shek. She was a charming and complex woman. Chennault was under her spell. Maybe it was because she was American educated and spoke English with a southern accent. Over the years she showed an ability to charm other Americans as well. She was also well connected in China. Her husband was president. Her sisters had married Sun Yat Sen, founder of the Nationalist Movement. Even after his death, Sun was still a hero and his widow was popular. Her brother, T.V. Soong, was finance minister and general man of all work in the nationalist government. Chennault saw her as a princess and was devoted to her.

It soon became clear that China needed better planes and more experienced pilots. Chennault and T.V. Soong visited the United States. Somehow, details are disputed, they returned with the promise of 100 Curtiss P-40s. Chennault also got permission to tour air bases and offer Army, Navy, and Marine pilots $600 a month to fly for China. In addition there was a $500 bonus for each Japanese plane shot down. Flight leaders were offered $675 and squadron leaders $750. Compared to rates of pay in the armed forces of the U.S., these were huge numbers.

American Volunteer Group

Pilots who chose to join the American Volunteer Group signed a contract to operate aircraft for Central Aircraft Manufacturing Corporation (CAMCO) which operated in China. They would serve from 4 July 1941 to 4 July 1942. The pilots who signed on for this adventure were a mixed lot. Tex Hill signed on because he was the son of missionaries who had served in China. Greg Boyington signed on because he was an alcoholic and in debt. The money looked good to him. Abilities also varied. Some were fighter pilots; others were bomber pilots. They all traveled to China by boat listing cover occupations like circus acrobat.

Once they arrived in Asia, they went back to school learning fighter tactics according to Chennault. They studied Japanese planes, especially the Zero. Chennault had observed Zero flying over China and had sent a report on it to U.S. intelligence. The report was filed and forgotten. Chennault had also analyzed the Zero and developed tactics to defeat it. Exactly what these tactics were is not clear, but the Flying Tigers were sold on them. They sat through classes in the morning and flew in the afternoon.

The basic idea behind the tactics was quite simple. Never turn with a Zero. Any P-40 that tried to dogfight with a Zero was in trouble. A number of historians have concluded that the basic move had to be a diving pass at the Zero followed by a diving escape. The P-40 was heavier and stronger than a Zero. It could stand dives that would tear the wings off a Zero. But the brutal fact was the Zero could out climb and turn tighter than the P-40. Chennault also taught his Tigers to fly in teams of two. He may even have invented the “thatch weave.” Some books say that a naval officer got a promotion for inventing tactics Chennault originated. The Thatch in “thatch weave” was a naval officer. Learning these tactics did not come easy. The Flying Tigers started with 100 P-40Bs. By the time they got into combat only 45 were left. The rest had been destroyed in training. One Tiger was declared an honorary “Japanese Ace” because he destroyed five P-40s during training.

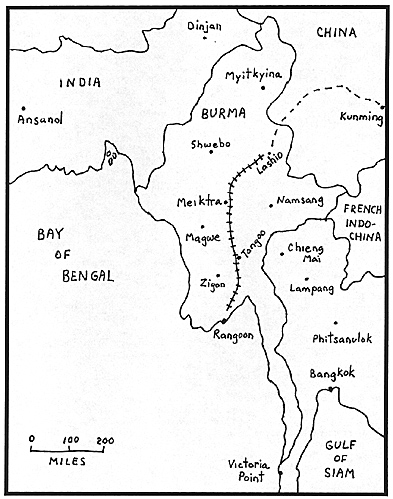

China had two missions for the Flying Tigers. First they needed protection against Japanese air raids on Chinese cities. China was receiving aid over the Burma Road, which ran fron Rangoon, Burma up over the Himalayas to Kunming, China. Flying Tigers were to protect the Burma Road. As a result, the Flying Tigers were stationed at two bases: Tangoo near Rangoon and Kunming in China.

The Rangoon situation was far from ideal. There was no net of observers to give warning of air raids. The Flying Tigers shared the air base with an RAF squadron (67 squadron) flying Brewster Buffaloes. Most of the RAF pilots were from Australia and New Zealand, but to the Tigers they were all British. There was little cooperation between the two units. When an air raid came in, they both took off as fast as they could. Their respective runways angled toward each other, so their take-offs crisscrossed each other. Miraculously, there were no mid-air collisions. On the ground there was a cultural collision. The Flying Tigers were as undisciplined on the ground as they were thoroughly disciplined in the air. They wore cowboy boots, wore revolvers in holsters, and were casual about shaving. Chennault played baseball and poker with them. They drank heavily, complained about the food, and got diseases from Chinese women. But in the air they were truly tigers.

Missions Begin

The fighting started December 20, 1941, over Kunming. Ten Japanese bombers attacked. Only one returned. The first and second squadron of the Flying Tigers shot down six bombers. Three more were damaged and crashed alter. Chennault was not pleased. “Next time get them all.” Three days later Rangoon was hit, and the third squadron inflicted similar damage on the attacking Japanese. The Flying Tigers would go on to compile an outstanding record against the Japanese.

They were credited with destroying 286 Japanese planes in the air and 240 on the ground. During that time only four Flying Tigers were lost in air combat. They lost six during strafing missions, three in training, and three to enemy bombing attacks. Out of a group of 87 pilots, 37 became aces, with ten double aces. They did this with a plane many experts called obsolete. Chennault, the rebel who had left the Air Corps a captain, was welcomed back as a general. The Army Air Corps wanted all the Flying Tigers to join up after their contract with China expired, July 4, 1942. Many were not interested. They resented the pressure from the Army and, in al honesty, they needed a rest.

Some quit early and were already cashing in on their fame. Two of them wrote a screenplay for a John Wayne movie entitled “The Flying Tigers.” Any resemblance between the movie and reality was accidental. Some pilots did stay to fight in China. Some died in later combat. Greg Boyington went back to the states early because of clash with Chennault. He would later lead a U.S. Marine fighter squadron and win the Congressional Medal of Honor. After the war, some of them started the Flying Tiger airline. It was a name Americans would recognize for decades. The Flying Tigers were a legend in their own time.

Like most legends, the story of the Flying Tigers exaggerates some and neglects some awkward facts. Let’s start with the name. Officially they were the American Volunteer Group (AVG), serving as part of the armed forces of China. It was the media that used the name Flying Tigers.

In defense of Rangoon, the 67 Squadron RAF is hardly mentioned. Of course in the RAF official history, the AVG is barely mentioned and the effective air defense of Rangoon is credited to 67 Squadron. The next two items are common to all fighter pilots. They claimed to fight the famous Zero, and they claimed more planes shot down than the enemy confirms. To read the memoirs, you would think the only fighter they met was the Zero. In fact, the AVG never fought Zeros. The Zero was a navy fighter and had been pulled out of China for use in the Pacific. The AVG fought the Japanese Army Air Forces and their Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa, and the most common fighter they met was the Nakajima Ki-27 “Nate.”

Like every fighter unit I have ever researched, the AVG reported fighting the most famous and deadly plane the enemy had. They also claimed and were paid for shooting down 294 planes. Reconstructed Japanese records show about 115 planes lost. There is some margin for error, but no less than 110 and no more than 120 covers the range. These numbers are based on Daniel Ford’s review of Japanese records. He is the only writer I know of who cross-checked the numbers. By the time I found his book and read it, we had been playing the game for years. As I said at the start, the game is based on the legend.

In the American press reports of World War II, “Zero” was a sort of generic term for “Japanese plane.” Even light bombers were sometimes labeled “Zero” in the press and in some history books. Also there were many times, starting with Pearl Harbor, when P-40s and Zeros did in fact fight. So the game is not a pure fantasy exercise.

Bibliography

Books

Angelucci, Enzo and Paolo Matricardi. World War II Airplanes, vol. 2 (1977).

Bond, Charles R. and Terry H. Anderson. A Flying Tigers Diary (1984).

Boyington, Gregory “Pappy”. Baa Baa Black Sheep (1958 and 1977).

Bueschel, Richard M. and Richard Ward. Mitsubishi A6M 1/2/-2N Zero-Sen in Imperial Japanese Naval Service (1970).

Bueschel, Richard M. and Richard Ward. Nakajima Ki 27A-B in Japanese Army Air Force. Manchoukuo - IPSF RACAF-PLAAK & CAF Service (1970).

Caidin, Martin. The Ragged, Rugged Warriors (1966).

Caidin, Martin. Zero Fighter (1969).

Chennault, Claire L. Way of a Fighter (1949).

Craven, W.T. and J.L. Cate. The Army Air Forces in World War II, vol. I Plans and Early Operations, January 1939 to August 1942 (1948).

Ford, Daniel. Flying Tigers: Claire Chennault and the American Volunteer Group (1991).

Franks, Norman L.R. Aircraft Versus Aircraft: The Illustrated Story of Fighter Pilot Combat Since 1914 (1986).

Gamble, Bruce. Black Sheep One: the Life of Gregory “Pappy” Boyington (2000).

Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. Flying Colors (1981).

Greenlaw, Olga. The Lady and the Tigers (1943).

Heiferman, Ron. Flying Tigers: Chennault in China (1971).

Hotz, Robert B. With Ceneral Chennault: the Story of the Flying Tigers (1943 and 1980).

Howard, James H. Roar of the Tiger: From the Flying Tigers to Mustangs: a Fighter Ace’s Memoir (1991).

Liu, F.F. A Military History of Modern China, 1924-1949 (1956).

Ienaga, Saburo. The Pacific War 1931 - 1945 (1968).

Lopez, Donald. Into the Teeth of the Tiger (1986).

Miller, Milt. Tiger Tales (1984).

Okumiya, Masatake and Jiro Horikoshi with Martin Caidin. Zero! (1956).

Park, Edwards. Fighters: The World’s Great Aces and their Planes (1990).

Richards, Denis. Royal Air Force, 1939 - 1945, vol. II (1954).

Pistole, Larry M. The Pictorial History of the Flying Tigers (1981).

Romanus, Charles F. and Riley Sunderland. Time Runs Out in CBI (1959).

Sakai, Saburo with Martin Caidin and Fred Saito. Samurai! (1978).

Scott, Marvin R. Games for Teaching World History (1983).

Scott, Robert L. Flying Tigers: Chennault of China (1959).

Scott, Robert L. God Is My Co-Pilot (1943 and 1966).

Seagrave, Sterling. Soldiers of Fortune (1981).

Seagrave, Sterling. The Soong Dynasty (1985).

Shamburger, Page and Joe Christy. The Curtis Hawk Fighters (1971).

Shultz, Duane. Maverick War: Chennault and the Flying Tigers (1987).

Smith, R.T. Tale of a Tiger (1986).

Stilwell, Joseph. The Stilwell Papers (1948).

Toland, John. The Flying Tigers (1963).

Wedemeyer, Albert C. Wedemeyer Reports! (1958).

Wells, H.G. Little Wars (1970).

Whelan, Russell. The Flying Tigers (1972).

Young, Peter, ed. The Wargame (1972).

Videos:

Great Warbirds of World War II (1997).

Flying Tigers (1942).

P-40, Way of the Warhawk (1942).

More Flying Tigers

- Historical Background

Air Combat Tactics

Wargame Rules

Robert L. Scott: Historical Campaign

Model Templates

Back to Table of Contents -- Lone Warrior #136

Back to Lone Warrior List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Solo Wargamers Association.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com