The first time the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor their force was spotted by patrol planes with disastrous results. So the next time, the Japanese adjusted their plan so that the fleet would be better hidden. The attacking planes came in from the North and scored a great victory. These two wargames played out by high level Japanese naval officers helped them decide to take the risk and launch a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

The first time the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor their force was spotted by patrol planes with disastrous results. So the next time, the Japanese adjusted their plan so that the fleet would be better hidden. The attacking planes came in from the North and scored a great victory. These two wargames played out by high level Japanese naval officers helped them decide to take the risk and launch a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

By 1941 Japan was faced with a dilemma. Since 1931 they had been at war with China. The "China Incident" promised great rewards, but as the Japanese army conquered large areas of China it found the cost very high. True, Japan got Manchuria and its resources and conquered rich rice-growing lands, but the Chinese government continued to resist. China was a large country that seemed to require endless commitment of forces. To make matters worse, China had friends who pressured Japan to get out. The start of World War 11 in Europe in 1939 served to distract the European powers. Britain, France, and Holland were too busy to put much energy into saving China. In fact their holdings in Asia were weakly defended and a temptation to Japan. The United States was still a problem. The Americans pressured Japan to withdraw from China. They imposed a trade embargo on war materials, particularly steel and oil.

Japan was a small country with a large population and few resources. China provided some needed materials but not oil. As the American embargo went on, it became a threat to Japan. Their petroleum reserves were dwindling. Japan faced a nasty dilemma. They could withdraw from China only at the cost of great loss of face before the world -- unacceptable. Or they could strike out and seize rich oil deposits in the European colonies. This would in turn probably lead to a war with the United States -- very risky.

Admiral Yamamoto of the Imperial Japanese Navy proposed the daring idea of an attack on the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. There were serious technical problems, but the British raid on Taranto had shown that an airborne torpedo attack on a fleet in harbor could be pulled off. It would take some modification on the torpedoes and careful planning, but it could be done. It was still risky, but time and oil was running out.

The decision was postponed. The Japanese government dispatched a team of negotiators to the United States. Perhaps a face-saving compromise could be arranged. It not .... Meanwhile the Japanese military began preparation for a powerful attack on Malaya, Singapore, Burma, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies. If Japan had these, she had the oil, tin, rubber and rice she needed. In even deeper secrecy the navy gathered a force of aircraft carriers and escort vessels. They trained in remote areas and observed strict radio silence. Even some top government officials did not know about the plan. The crews were only told after they had gone to sea. If there was no political solution, the military would strike. While a massive Japanese force moved toward Southeast Asia, the carriers would move north and launch an air attack on Pearl Harbor just after war had been declared. The month of November, 1941, was a busy time for the Japanese government, preparing for a wider war while trying to negotiate an honorable peace. The Japanese diplomats in Washington apparently had no idea how much was riding on their efforts.

Meanwhile the Americans were debating about entering the war. President Roosevelt was edging toward involvement in the European war, but there was a sizeable and loud isolationist movement. The Midwest was considered isolationist territory, but even in Des Moines, Iowa readers of the Des Moines Register were reading about the war.

Even the toy market was reflecting the war. Christmas shoppers could buy a wind-up tank for $1.98, a mechanical bomber for $.69, and a submarine for $.98. These were offered in the December 1 Register. On page 6 there was heavier reading, analysis of the Japanese forces by an expert on military affairs. He assured his readers, "It is in the air that the Japanese relatively are the weakest ... In quality - in all types our planes are rated superior.... The Japanese may not know the full extent of the forces now surrounding them, but experts not given to idle talk give assurance that they are sufficient to check and if necessary to destroy Japan." The next day the paper ran a map on page 2 showing key positions around Japan. They included Manila, Alaska, Singapore and "Islands." Pearl Harbor was not labeled on the map.

In Washington the negotiations to end the crisis continued. American Army and Navy intelligence units were following Japanese military moves. When Japanese ships communicated by radio, American operators could locate the ship by radio direction finding. Over time they could plot movements of ships and analyze patterns. Clearly, something big was up. There was an increase in radio traffic indicating that the Japanese were moving ships and getting ready to do something. The available information indicated a move toward southeast Asia. There was one gap. There were no radio intercepts from the Japanese carriers. On November 27, 1941, the Chief of Naval Operations sent a message to all commanders.

"This dispatch is to be considered a war warning. Negotiations with Japan ... have ceased and an aggressive move by Japan is expected within the next few days ... against the Philippines." It also listed some other possible targets and urged "continental" forces to take "measures against sabotage." There were later messages advising commanders not to alarm civilians or provoke Japanese attack. The army intelligence was less emphatic about things. The difference of opinion and the qualifications tacked on weakened the "war warning."

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese sent the final cable to their ambassadors in Washington directing them to declare war. American intelligence had the message decoded before the Japanese embassy did. Warnings were sent out to all U. S. forces, but the message to Pearl Harbor was delayed a bit and sent by commercial cable.

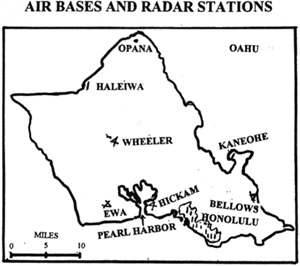

At Pearl Harbor, General Short and Admiral Kimmel, army and navy commanders, had not prepared for a direct attack. They stressed training and defense against sabotage. The Army ran the Aircraft Warning Service, but radar was a new device, and leadership was confused. The plotting table was installed on November 17, but had to be repainted. This took a week, and it took another week to train plotters. There was confusion about who should command radar. As a result, the system was not running 24 hours a day. It was turned on in early morning and off again at 7:00 a.m. On December 7, 1941, two privates were practicing on the radar at Opana station at 7:03 a.m. when they saw a large number of planes north of Oahu. They reported them to control, and the officer in charge told them to "forget it."

The Navy ran some routine patrols near Pearl Harbor. At 6:51 a.m. the destroyer Ward sent the following message. "We have dropped depth charges upon submarine operating in defensive sea area." The officers on duty at the headquarters were skeptical and were still trying to verify the report when bombs started dropping at 7:55 a.m. Shortly after that, they were sending "Air Raid Pearl Harbor. This is no drill."

Two waves of Japanese aircraft hit Pearl Harbor. The Army's fighter planes were mostly destroyed on the ground. The U.S. Navy's battleships were sunk or damaged. American casualties were heavy. When the attack was announced, the debate about entering World War II ended. On December 8, 1941, America entered the war as a unified, aroused, and angry nation.

While the Japanese could take satisfaction in their successful surprise attack and light casualties, there were questions. Should there be a second strike to finish the destruction of Pearl Harbor? Where were the American carriers? They had hoped to destroy them, but they were not in port. Should they have attacked the oil storage tanks? This could have destroyed the American fuel supply crippling them for months.

Solo wargamers may want to build scenarios based on any of the above options. If you have a strategic level game, maybe you could game out how a different attack would have changed the war. For me, one of the more interesting scenarios is a battle between the U. S. carriers and the Japanese striking force. Two U.S. carriers were at sea near Pearl Harbor. The Enterprise was 150 miles from Pearl Harbor on a line with Wake Island. The Lexington was near Miidway. What if they engaged the Japanese? The most interesting question for me is what would have happened if the fighters had scrambled to intercept the Japanese? My guess is that we would have still lost a lot of planes plus their pilots, and the damage might have been as bad or worse. I have often dreamed of dozens of wargames playing out these scenarios and each reporting the result in Lone Warrior. It would give us some new insights. If you have a World War II air combat game or a World War II strategic game, why not give it a try and submit a report?

I have never felt it was quite fair to write an article requiring that the reader own a certain game. I know that articles like "Revised land slug rules for Death Ray 11 variant b" are very meaningful to owners of the game, but to me they are just gibberish. Therefore, I usually try to provide some rules and even models for playing a game. This time is different. I decided I was in a rut, so I started with two limitations: no dice and no models. By doing so I have managed to alienate most of you I know. We all love dice. Dice are pretty. They sparkle and fell neat in the hand. We keep them in our little leather treasure purses. Did I say purses? Oops, wargamers are supposed to be macho types. Model builders love their models too. Some of us spend hours painting details on them that are only visible to an electron microscope.

Sometime soon I'll provide a game with models, maps, and dice that has P-40s fighting Zeros. Promise. But that is for later. Now try this Pearl Harbor game. The assumption of the game is simple. When the radar report came in, U.S. Army pursuits were notified and scrambled. You may find this game a little different but it is fun.

There are two versions of the game so far. The earliest version assumed that the player was controlling masses of planes. The revised version has the player flying one plane at a time. These are followed by a note on conspiracy theories. I have also provided statistics on the battle and pictures of the planes with performance specifications. Happy landings.

Statistics

Japanese task force - Admiral Nagumo

6 carriers: Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu, Soryu, Shokaku, and Zaikaku

2 heavy cruisers: Chi Kuma and Tone

2 battleships: Mei and Kirishima

9 destroyers

1 light cruiser

8 oilers

3 submarines

Japanese Aircraft - first attack 0750

40 Kate torpedo bombers

49 Kate level bombers

51 Val dive bombers

51 Zeke fighters

second attack

54 Kate level bombers

78 Val dive bombers

36 Zeke fighters

U.S. Army Air Corps Pursuits

62 P-40B or C at Wheeler

25 P-40B or C at Haleiwa (52 in commission)

12 P-40B or C at Bellows

39 P-36 available (20 operational)

not in the game

14 P-26 (10 operational)

11 F4F-3 Wildcats at Ewo air base

Casualty Figures

U.S. Navy 2008 killed 710 wounded

Marines 109 killed 69 wounded

Army 218 killed 364 wounded

Civilians 68 killed 35 wounded

Damaged

Lost Battleships Arizona and Oklahoma

Sunk or beached but later salvaged battleships West Virginia, California, and Nevada and mine layer Oglala

Damaged Battleships: Tennessee, Maryland and Pennsylvania

Cruisers: Helena, Honolulu and Raleigh

Destroyer: ShawSeaplane tender: Curtis

Repair ship: Vestal

Planes destroyed: 96 army 92 navy

Planes damaged: 128 army 31 navy

Japanese losses:

9 fighters, 15 dive bombers, 5 torpedo planes.

1 large submarine and 5 midget submarines.

Personnel lost: 55 airmen

9 crewmen midget submarines

unknown number large submarines

Bibliography

Angelucci, Enzo and Paolo Matricardo. World War II Airplanes, Volume 2 (1977).

Barker, A. J. Pearl Harbor (1969).

Bueschel, Richard M. and Richard Ward. Mitsubishi A6M 1/2/-2N Zero-Sen in Imperial

Japanese Naval Air Service (1970)

Caidin, Martin. The Ragged, Rugged Warriors (1966).

Craven, Wesley Frank and James Lea Cate. The Army Air Force in World War II (1975).

Goldstein, Donald M. and Katherine V. Dillon. The Way It Was: Pearl Harbor the Original

Photographs (1991).

Jones, Lloyd S. U.S.Fighters: Army-Air Force 1925 to 1980s (1975).

Lindley, Emest. "A Hard Choice for the Japanese", The Des Moines Register, December 1,1941, p. 6,

Lord, Walter. Day of Infamy (1957).

Morison, Samuel Eliot. Two Ocean War (1963).

Potter, E.B. BuIl Halsey (1985).

Prange, Gordon W. At Dawn We Slept: theUntold Story of Pearl Harbor (1981)

Willmott, H.P. Pearl Harbor (1981).

Wohlstetter, Roberta. Pearl Harbor Warning and Decision (1962).

Video. Tora! Tora! Tora!

More Pearl Harbor

-

Introduction

How to Play Pearl Harbor

Sample Game - Air Rifle Version

Pearl Harbor - The Aircraft

Note on Conspiracy Theories

Game Diagrams

Back to Table of Contents -- Lone Warrior #134

Back to Lone Warrior List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Solo Wargamers Association.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com