On 24 June, three days after the verbal alert, the 112th received formal orders to embark for Aitape. Two days later General Cunningham and his staff arrived by air at the Tadji strip. The 112th, less its rear echelon of about 100 officers and men, embarked aboard twelve Landing Craft Infantry (LCIs) on 26 June. The unit was understrength, averaging between 140 and 150 men per troop of an authorized 162-man strength, The men were coming off a two-week "rest" at Finschhafen, which meant that they lived in company tents, ate communal meals, and remained exposed to the elements and exotic

diseases of New Guinea. But at least they were not shot at by the Japanese.

On 24 June, three days after the verbal alert, the 112th received formal orders to embark for Aitape. Two days later General Cunningham and his staff arrived by air at the Tadji strip. The 112th, less its rear echelon of about 100 officers and men, embarked aboard twelve Landing Craft Infantry (LCIs) on 26 June. The unit was understrength, averaging between 140 and 150 men per troop of an authorized 162-man strength, The men were coming off a two-week "rest" at Finschhafen, which meant that they lived in company tents, ate communal meals, and remained exposed to the elements and exotic

diseases of New Guinea. But at least they were not shot at by the Japanese.

As they embarked, the troops carried individual equipment and weapons, five days' ten-in-one rations, one unit of fire, kitchen equipment, and a small amount of canvas. [5] These items were the infantryman's basic survival kit, so it is worthwhile to examine their contents. The ten-in-one ration was meant to feed ten men for one day, providing, in theory, about 3,660 calories per man per day. [6]

The ration held a breakfast, lunch, and dinner meal, given variety by different dehydrated cereals, meat, and vegetables. About one soldier in three considered the food sufficient, but another third did not like it. [7] The popularity of the ten-in-one ration resulted from its sundries, packs of cigarettes, matches, toilet paper, halazone tablets, and a can opener in each ration--luxuries to the combat soldier.

The other basic ration was the K ration, with three meals separately wrapped in waxed paper or cellophane, making it lighter in weight and more compact, allowing the soldier an easier time carrying his food supply. Unfortunately, it was not packaged for the tropics, where after three days, the boxes would come apart in the high humidity.

Troops in the 112th also "had a tendency to carry too much equipment for personal comfort," and their officers worried that the soldiers might discard essential articles to compensate for the load. [8] Men, for example, generally kept their ponchos to ward off the rain, but occasionally discarded blankets or

half-blankets and spent the chilly tropical night shivering. To sum up, on any given night a rifleman's lot was to be afraid, perhaps hungry, probably wet, and surely cold.

The dismounted cavalryman's weapon was his most important tool for survival. His uniform could be in tatters and his boots rotting away, but the working parts of his weapon had to be spotless. The high humidity of the rain forest, coupled with the varieties of dirt, sand, and bugs that could work their way into a weapon and jam it, forced the men to spend extra time and care cleaning their weapons. Browning automatic rifles (BARs) and carbines required special care. Each man carried his ammunition, a unit of fire. This varied from 750 rounds for a .30-caliber BAR operator to 150 rounds for a rifleman. Machine gunners obviously required more ammunition and thus had teams to carry the gun and its ammunition, 2,000 rounds for a light machine gun and 1,200 for a water-cooled heavy machine gun. The 60-mm mortar crews of the 112th Cavalry had fifty rounds per mortar. To lug these weapons and their accompanying ammunition through the jungle in the sweltering heat was exhausting labor. The men compensated by reducing their loads--that is, by not carrying complete units of fire. The 112th's voyage to Aitape was uneventful, and the RCT, less its artillery

battalion, landed there on 28 June. Japanese scouts of the 1st Battalion, 237th Infantry Regiment, 41st Infantry Division, observed some phase of these landings and reported to 18th Army that "many enemy transports and LSTs" were active near Aitape. [9] Japanese patrols, however, could get no closer and, thus, were unable to identify the 112th, a deficiency for which they would later pay heavily.

The evening of the next day, Brig. Gen. Clarence A. Martin, commander of the Eastern Defense Command, ordered the 112th to join the covering force along the Driniumor River. Its mission was "to delay the enemy to the maximum extent possible without sacrifice of troops." Martin also instructed the 112th to assume responsibility for the defense of Afua, the southern anchor of the Driniumor line, and assigned to General Cunningham's command the 3d Battalion, 127th Infantry Regiment, plus attached medical personnel.

There was little time for sleep, for most of the men spent the night preparing for the move inland. Two men per troop (twelve total) and a portion of the Service Troop remained near Aitape as a rear echelon. Regimental bandsmen became litter bearers. All heavy weapons (81-mm mortars, 37-mm antitank guns, and rocket launchers) were left behind. The antitank platoon, Headquarters Troop, instead carried heavy machine guns and functioned as a machine gun platoon. The 81-mm mortar crews from the Weapons Platoon converted to ammunition bearers and served as an oversized rifle platoon. Riflemen, BAR operators, and submachine gunners carried a modified unit of fire; machine gunners, a unit; and 60-mm mortarmen, a half unit. Everyone carried three days' ten-in-one rations in their packs. [10] Replacements carried ammunition and supplies so that the experienced combat veterans could be put on the firing line. [11] Their lowly status as porters was not lost on the replacements. Native bearers also transported supplies.

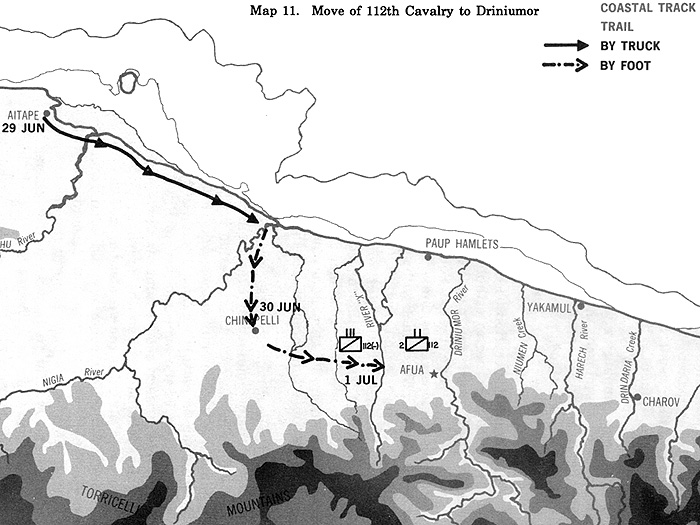

The regiment moved by truck from Aitape on the morning of the twentyninth and dismounted at the Nigia River, where an engineer ferry boat transported the troops across the river (see map 11). The limited fifty-man capacity of the ferry made the crossing a slow affair. From the river, Eastern Defense Command expected the 112th merely to make a five-mile forced

march through no-man's-land and, after reaching Chinapelli, to establish a defensive position there. A tropical rainstorm made this "normal" activity more difficult than usual. Shoes muddy, heads down, carrying thirty to forty pounds of equipment, the men plodded though the downpour toward Chinapelli. Torrents of rain washed over the long column and over the men who were slipping and sliding through the now deep mud of the trail. Exhausted by the march, they still had to form their defensive perimeter. After the skies had cleared, a C-47 flew over and dropped provisions at Chinapelli. Cold rations, wet clothing, and a night in the jungle were the cavalrymen's reward for their first day in the field at Aitape.

Orders from Persecution Task Force directed the men to continue their

eastward move in order to establish defensive positions and a patrol base along River X, which ran parallel to and about 4,100 meters west of the Driniumor. Meanwhile, the 2d Squadron would advance to the Driniumor and organize defensive positions near Afua. Their deployment would allow the 3d Battalion, 127th Infantry, then occupying the Afua positions, to shorten its line by closing to the north. [12] General Martin's 32d Division G-3 had prepared careful tactical plans for the 112th Cavalry premised on the assumption that the 112th was equivalent to a full-strength infantry regiment. [13]

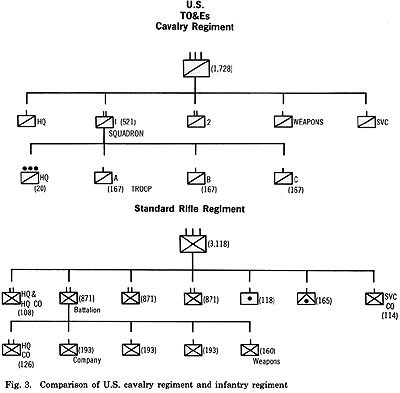

Instead of the 3,000 men he expected, Martin found himself with slightly more than 1,500 men to cover a frontage originally designed for two or three times that number (see fig. 3). They would have to do.

The next day's march was even worse than the first. A seventy-five man

detachment remained at Chinapelli to patrol between there and River X, as well as to cover the Palauru-Afua trail. In addition, they were expected to maintain wire communications from River X to the rear, a dangerous job, for Japanese patrols would cut the wire and wait in ambush for repair crews. The rest of the men marched to River X in another downpour. The hilly terrain crisscrossed by many small streams made this trek more physically demanding than the previous day's.

The first few men up an incline would strip off the vegetation, and the constant tramping by those following in the long column would soon reduce slopes to muddy

slides. Just reaching the top of such a slope burdened with thirty or forty pounds of

equipment on one's back required the use of every muscle and expended enormous

energy. But there were no stragglers, except for two sick men who returned to Chinapelli shortly after the 112th's departure. The regiment, less the 2d Squadron, which had pushed ahead toward the Driniumor, put up a defensive perimeter along the west bank of River X. After two days of exhausting marches in heavy rains and mud, eating cold rations, and sleeping in wet clothes, Persecution Task Force moved the 112th's unit symbol to River X. In peacetime, this feat alone would have been considered an

accomplishment; now it was merely a prelude to bitter days ahead.

The 2d Squadron spent the night of 30 June southeast of River X and the next morning moved to the Driniumor. Under scattered clouds and intermittent showers they relieved the 3d Battalion, 127th Infantry, at 1100, placing Troops E and F forward on the riverbank and Troop G in reserve, the approved

"two up-one back" configuration, despite the rugged, close terrain. Everything was quiet, and no patrols were sent out.

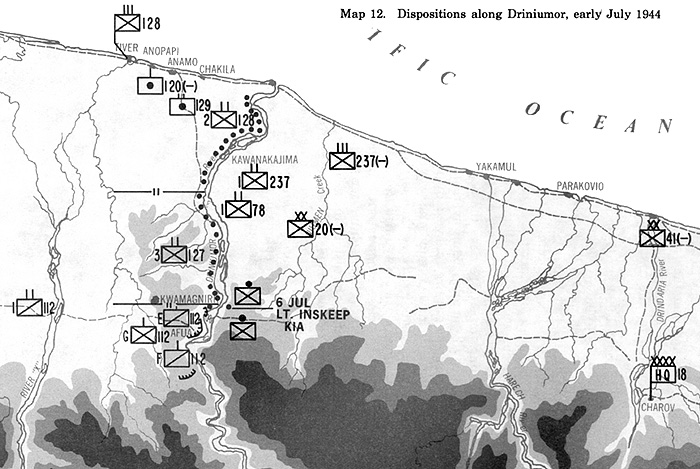

Regimental headquarters, however, did dispatch four patrols to check the security of the 112th's flanks. After the 3d Battalion had moved out to the north, the 2d Squadron was alone anchoring the covering force's south flank. Its isolation, in part, was a function of the jungle terrain features that fragmented large formations into scattered pockets remote from one another. The men knew what was within a few yards of their particular entrenchment and little more.

As for the enemy situation, they depended on their patrols, the reports sent by wire from neighboring units, and those transmitted from higher headquarters. The so-called big picture of the campaign did not interest them. Their concern was more basic: to stay alive.

Members of 2d Squadron spent their first full day at Afua constructing a defensive perimeter, improving fields of fire by clearing the kunai grass from the small islands or sand spits in the river as well as cutting jungle vegetation on the flanks and rear of their perimeter. They established telephone communications with the main body of the 112th. A liaison party from the 120th Field Artillery Battalion joined regimental headquarters. The 2d Squadron then proceeded to register artillery and mortar fire on locations in front of both River X and the Driniumor.

Meanwhile 1st Squadron and the rest of the 112th worked feverishly on their defensive positions near River X. Generally speaking, troops engulfed in jungle fighting had no shelter. The only efficient protection combat troops had was the "jungle poncho" (a rubberized cloth about five by six feet), which was thrown over the back and head and strapped under the chin. [14]

In place of rain, the men now worked on 3 and 4 July under a broiling sun that burned and blistered their exposed skin. Mosquitoes, insects, worms, and leeches latched onto their sweating bodies as the soldiers excavated the pits that would be their crude shelters and fighting positions. Besides the work on entrenchments, twenty-five men cut a trail through the jungle vines and ferns from the command post toward the Tiver River for use as a medical evacuation route.

An Australian and forty natives arrived at River X to assist in evacuation and supply efforts. Although the extra labor was helpful in stockpiling supplies at the 112th's base, the natives' blissful disregard of the 112th's sanitary regulations within the perimeter made their presence a mixed blessing. The 112th's small buildup continued as the troops laid ground panels on dry portions of the riverbed to identify a drop zone for

aerial resupply. The original site proved too rocky, and about half of the air-dropped supplies broke on impact. Yet another nearby drop zone had to be cleared by machetes of brush and vegetation.

Meantime, the original drop zone became so contaminated, smelled so bad, and became so thick with flies that a third drop zone had to be constructed. Air resupply then functioned better and provided ten-in-one rations, blankets, mail, and new boots for the troops. Officers had to badger some of the men about sanitation and digging proper latrines. Troop commanders handed out Atabrine, salt tablets, and halazone to the unit. Threatening court-martial, they ordered troops not to use kunai grass for beds or shelters because of the danger of bush typhus.*

The concern was as much practical as humanitarian. A sick man would have to be evacuated, and that meant fewer combat soldiers available to fight. Losses from disease most affected rifle companies, which seldom had more than two-thirds of their authorized strength at any one time, so every man was precious. **

Paradoxically these same men had to live in the harshest natural surroundings and were exposed to the greatest danger in combat. They compensated by building themselves what amounted to a primitive fortified village, which a time traveler from the Middle Ages would probably have recognized as a defensive hamlet.

After 2 July, intensive patrolling north and south along the Driniumor, east to Niumen Creek, and west along the trail to River X characterized the 112th's activity. Patrol leaders were under orders to observe the enemy, not to fire on them. [15]

These patrols had a dual purpose. The obvious, stated goal was to collect intelligence about the enemy and, if possible, to capture

a prisoner. Likewise, patrols provided terrain information unavailable on the inadequate maps issued to the units. A third, but unstated, purpose of patrolling was to build the men's confidence, to familiarize them with the terrain, and to train replacement officers and enlisted men in overcoming their initial fear of the unknown. But patrolling was dangerous work. The stress and tension of men on patrol never slackened.

The 112th, like other American units fighting in the Pacific, did not believe in taking Japanese prisoners. Prejudice tinted the American soldier's view of the Japanese and increased the savagery of combat. If the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor brought the cauldron of anti-Japanese feeling to a bubble, U.S. military and civilian propagandists continued to stir the witches' brew in order to foment a hyperpatriotism they believed would be beneficial to the war effort. Japanese atrocities, such as using captured 112th troopers for bayonet practice on New Britain, served to confirm stereotypes of the Japanese as subhuman creatures who had to be killed. This refusal to take Japanese prisoners had important operational ramifications.

In the 32d Division's G-3 Journal for 4 July 1944 appeared the entry that "1 unarmed Jap killed on E bank of Driniumor River." Appended to this entry was the following handwritten note: "Another prisoner that could have told us if the 41st (Division) had arrived. What effect our bombing had had, possibly when the attack was expected, where were what units. These

troops seem to want to fight this war the hard way, they won't take a prisoner." [16]

The savagery went far beyond the 112th Cavalry. It infected troops of both nations. So the patrols went out daily to find the enemy and to kill unwary opponents. On 2 July, a Troop E patrol was the first from the 112th to spot the enemy when it saw six Japanese crossing the Driniumor 540 meters south of Afua, but the Japanese soon vanished into the deep jungle. The same day the 112th suffered its first casualty, a band member who accidently shot himself.

During the next few days, patrols gradually extended their range and their fighting strength. For example, on 6 July a forty-eight-man patrol from Troop B, led by two officers, left Afua to destroy a suspected Japanese radio installation near Charov. According to their maps, Charov appeared just west of the Drindaria River, but it was actually on the east bank. By staying close to the Torricelli foothills and scouting only the west bank, this fighting patrol inadvertently sidestepped the Japanese 20th and 41st Infantry divisions, which were then massing about halfway between Afua and the coast for their planned 10 July attack.

The inaccurate maps probably saved the men's lives. The terrain was so rugged and thick with vegetation that the Americans could pass undetected near hundreds of Japanese troops and return to their base unharmed. Other patrols reported evidence of Japanese activity, but no sightings, probably because of recurring showers, which further masked enemy activity. By about 6 July, the cumulative patrol reports had suggested that the Japanese were forming counter-reconnaissance screens along the Niumen Creek vicinity, where 112th patrols met determined Japanese opposition for the first time during the campaign.

On 6 July, about 1,000 yards northwest of Afua, a platoon from Troop F

walked into an ambush triggered by dug-in Japanese troops supported by machine guns (see map 12). The Japanese probably were a screening force for units of the 41st Infantry Division, which had arrived in the area that same day. Troop F's men blindly exchanged gunfire with the Japanese, but could not penetrate or flank the Japanese trail block. The patrol leader, Lieutenant Inskeep, was killed, after which the Americans withdrew.

Two days later a patrol led by Lt. Ray A. Titus again tried to penetrate the Japanese screening force to retrieve the body. The Japanese had set another ambush on a heavily jungled bank overlooking the ravine. Again there was a sudden outburst of gunfire followed by initial terror and confusion. Two American enlisted men were shot and wounded, but they claimed to have killed one Japanese soldier. Nevertheless, Titus's patrol could not retrieve the body.

This minor skirmish typified the hazards of jungle patrols. Sudden ambushes triggered at close range meant a high incidence of gunshot wounds. The abrupt stutter of

a light machine gun or bark of rifle fire was followed by shouting, screaming, confusion,

initial panic, and then more gunfire or a muffled grenade explosion as both sides

reorganized. More likely, after the first gunshots, one side or the other (sometimes both)

would run back into the thick vegetation for safety. This type of small unit action occurred over and over as the American patrols brushed against the Japanese screening forces who were covering the assembly of the main Japanese units.

Native bearers, with soldier escort, evacuate a casualty across the Driniumor River near Afua

Village. Note the shallowness of the river.

Native bearers, with soldier escort, evacuate a casualty across the Driniumor River near Afua

Village. Note the shallowness of the river.

*During the entire campaign, a total of 279 typhus cases resulted in sixteen deaths.

** For example, of an authorized 152 officers and 3,100 men, the 128th Infantry Regiment had 121 officers and 2,649 men present for duty on 29 June 1944. The 127th Infantry counted 117 officers and 2,861 men available. On 1 July the 112th Cavalry's six line troops had 46 officers and 885 men present of an authorized 48 officers and 972 men.

Chapter 4: US 112th Cavalry's Deployment to the Driniumor River

- Chapter 4: Situation Overview

Chapter 4: 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team

Chapter 4: To the Drinuimor

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com