Three weeks earlier, on 21 June 1944, the 112th Cavalry RCT had received verbal orders to prepare for a move from its base at Finschhafen.

Lt. Col. Philip L. Hooper, executive officer, 112th Cavalry, telephones operational orders received from Brig. Gen. Julian W. Cunningham, commanding general, 112th Cavalry.

According to the commander of the 112th Cavalry Regiment, Col. Alexander M. Miller III, members of the regiment knew that "something was in the works," perhaps even the invasion of the Philippines. Nevertheless, the initial information Colonel Miller received was purposefully vague, and the men in the unit had really no idea where it was going or what to expect once it arrived. Their only certainty was that they eventually "would contact the enemy and eliminate them.

[1]

The 112th was a Texas National Guard regiment. When it was federalized in 1940, draftees from Brooklyn, New York, Chicago, Illinois, and Iowa augmented its ranks. When it received orders for a Pacific Ocean deployment at Camp Clark, Texas, the regiment had to search for a jungle warfare manual. Once a copy was discovered, Maj. Philip Hooper had to read it aloud to the regiment's NCOs assembled in a poorly ventilated orderly room on a sweltering Texas day. Page after page of the manual described the dangers of snakebite, insects, and tropical diseases. For men who had never been outside the United States and knew little, if anything, about the Pacific

islands, it stimulated more fear than enlightenment about their assignment. Furthermore, the regulations dwelled on what could not be done in jungle terrain and unintentionally slighted what could be accomplished. So without much doctrinal assistance, the 112th shipped overseas in July 1942.

The officers and men did have the chance to become accustomed to the

environment of New Caledonia, where they spent nine months of intensive training. Brig. Gen. Julian Cunningham's rigorous discipline and realistic training helped to make the members of the 112th physically tough and would enable them to endure the hardships of living and fighting in the tropical rain forest that lay ahead. The 112th had the time, nearly three years, to train and to prepare itself for combat.

Its first combat operation was an unopposed landing on Woodlark Island in July 1943. After occupying Woodlark for six months, the regiment moved to Goodenough Island, was strengthened by the 148th Field Artillery Battalion, and was redesignated the 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team. The 112th's next operation, 15 December 1943, was a diversionary effort to assist the U.S. Marines' invasion of New Britain and resulted in near catastrophe.

Troop A, 2d Squadron, attempted a forced landing at Arawe, New Britain,

using rubber boats. Japanese 25-mm gunfire sank all but three of the fragile craft before they reached shore. Only the courage and willingness of the U.S. Navy minesweeper commander who sailed his ship into the cove and smashed the Japanese batteries with gunfire averted disaster. The survivors regrouped, eventually rejoined the 112th, and fought on New Britain for the next six months.

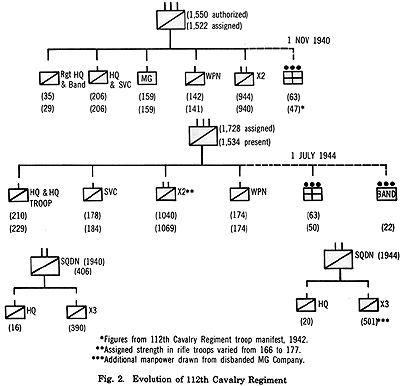

The jungle fighting, sickness, and incessant enemy bombing whittled the units down to about 1,100 from their authorized strength of 1,728. In June 1944, the 112th finally received orders for rest and reconstitution at Finschhafen. That respite lasted only a brief two weeks. During that time, though, replacements and troops returning to duty increased unit strength to 1,458, or 85 percent of TO&E strength (see fig. 2).

A variety of circumstances molded the 112th Cavalry. The men who formed

the nucleus of the outfit had known each other and soldiered together for a long time. By 1944 it was not uncommon for the members from the former National Guard regiment to have served with their unit for five, six, or even ten years. They knew, in the words of one veteran, whom they

could count on and who were the deadbeats. Draftees were organized around

this core of Texans. The veterans inculcated the new arrivals with their

traditions and the esprit of a cavalry outfit. Pride in themselves and their unit developed naturally, and no artifice was involved. The distinctive cavalrymen's uniform-breeches, knee-high boots, and cavalry hats-identified them as different, and therefore special, compared with other federalized National Guard units. The unit's longevity was its strength; it provided continuity, identity, and a sense of responsibility at a time when those qualities were much in demand.

In addition, even after its mobilization, the 112th was a small unit, about 1,700 authorized officers and men, or roughly half the size of the standard TO&E infantry regiment. The identity neither of the men nor of the unit was overwhelmed by a vast influx of newcomers in the form of draftees or volunteers. Officers at regimental or squadron level knew their men on a first-name basis and bred identity, cohesion, and a sense of comradeship into the ranks. In short, the 112th Cavalry possessed a high degree

of unit cohesion. [2]

Like any other unit, it had its share of problems. Brigadier General Cunningham commanded the 112th Cavalry RCT, but Colonel Miller had commanded the 112th Cavalry before it became an RCT. Their headquarters were collocated, and Cunningham would, at times, supersede Miller as regimental commander. Cunningham was a strict disciplinarian from the "Old Army" and was not the easiest commander to work with or for. The regiment relied on its company-grade officers for leadership, but at least one junior officer failed to carry out his combat assignment at Aitape for no apparent reason.

Moreover, junior officer losses on New Britain had been heavy. Their replacements were either promoted from the 112th's enlisted ranks or sent fresh from the United States. Only a few of the original troop officers remained by June 1944, as the currents of warfare had taken their toll of young officers or pushed them into higher, more responsible, command positions. Among the ranks was petty jealousy over promotions or lack of the same. Some replacements responded to the indoctrination

administered by the 112th veterans, but others resented the Texans' brashness. The men alternately feared, despised, or admired their officers. All felt that higher headquarters selected the unit for dangerous reconnaissance missions because of its cavalry designation, conveniently forgetting that the 112th was a dismounted cavalry regiment, in

effect a half-strength rifle regiment. They had few illusions about ever going home before the war was won. No one doubted that they would win, but everyone knew that the price could be high. Most regarded their service as a job that someone had to do.

They lived in the open in an oppressive tropical climate that debilitated the health of even the strongest among them. But that condition was only incidental to their mission to track down and kill other men in the jungle. Those exposed to the greatest danger, the riflemen and machine gunners on the front line, received the least rewards.

As a postwar report noted, the infantryman "can look forward only to death, mutilation, or psychiatric breakdown. He feels that no one at home has the slightest conception of the danger his job entails or of the courage and guts required to do one hour of it." [3]

Added to this was the constant fear. Most were afraid all the time, but at least their fear kept them alert and probably made some of them fight. There were those few whom S. L. A. Marshall described as "natural fighters," and they excelled in combat. But, for most, it was a constant strain to check their natural inclination for self-preservation. Given their dismal prospects for survival, why would they fight? Self-preservation motivated them as did the fear of severity of court-martial. The essential motivations

that kept these men going were "pride (self-respect) and the strong bond with [their] fellow soldiers." [4] They fought by themselves for themselves, and little else beyond that mattered.

Chapter 4: US 112th Cavalry's Deployment to the Driniumor River

Chapter 4: Situation Overview

Chapter 4: 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team

Chapter 4: To the Drinuimor

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com