The battles of Prague and Leuthen are primary

examples of Frederick's oblique order of attack. As

mentioned above, there were other instances of successful

use of that type of attack like Torgau. The following

discussion is an instance of its failure and on how, if the

troops moving to a flank were attacked while on the march,

it was most likely to fail.

The battles of Prague and Leuthen are primary

examples of Frederick's oblique order of attack. As

mentioned above, there were other instances of successful

use of that type of attack like Torgau. The following

discussion is an instance of its failure and on how, if the

troops moving to a flank were attacked while on the march,

it was most likely to fail.

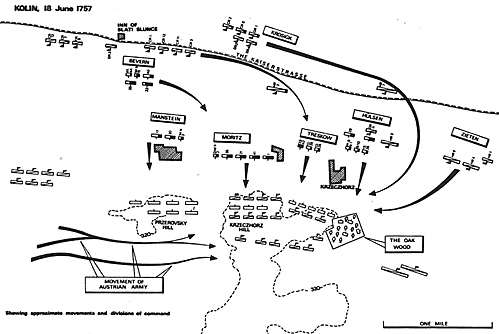

After winning the battle of Prague, Frederick established the siege of that city. Marshal von Daun, with 60,000 fresh troops, moved slowly to the relief of the beleaguered city. Frederick gathered all the forces he could spare from the siege, 34,000 men, and decided to attack Daun. The latter moved along the Olintitz-BrunnPrague line as far as Kolin. Frederick moved his army in the usual formation, covered by an advance guard consisting of 55 squadrons of hussars and dragoons and seven battalions of infantry. On debouching from the village of Planian, Frederick's vanguard discovered the Austrian army posted on the southern side of the road (the famous Kaiser-Strasse) on a semi-circular range of heights, extending from Krzeczor on the right to Brzesan on the left. The Austrian first line was posted half way up the slope, the second on the crest. The front was covered by villages, difficult ground and numerous artillery batteries which swept all the approaches.

Frederick decided to attack the Austrian right flank, or that nearest their line of retreat. He directed his vanguard to advance along the main road until nearly opposite Krzeczor and then leaving the road to move towards Radosvesnitz. He intended to support his advance guard with the whole army, from which he could advance and roll up the Austrian line.

This projected movement did not take into consideration some deployment problems related to keeping regular distances. This was essential to the success of Frederick's tactics especially with respect to the oblique order of attack. After the advance guard had reached Zlatysluntz and the head of the main body Novimesto, it became necessary to halt in order to correct the distances as much distance had been lost by defiling through the town of Planian.

The advance guard moved as directed, wheeled into line, attacked and carried the village of Krzeczor.

While this was being done, the main body of the army on its march along the front of the Austrian position was much disturbed by the Austrian light troops, which continually attacked their right flank. A battalion leader being much pressed, ordered his battalion to wheel to his right. By deploying his battalion to defend itself against the pressing Austrian light troops, the Prussian battalion leader did not intend to trigger what followed. He had not realized that wheeling his battalion to the right was the order to form line. It was taken up by the whole army in the rear, who wheeled into line also and attacked the Austrians near Chotzemitz while the leading portion of the main body continued its march.

A large gap was thus left in the long columns and the general commanding the first portion of the main body, hearing the firing, looked back, saw the remainder of the army in action, wheeled to his right and also attacked. Thus, the Prussian army made four disconnected attacks along the front. The Prussians fought well, and renewed their attack five or six times, but were unable to carry any of the Austrian positions, and also were forced to retreat with heavy looses of 12,090 casualties while the Austrians suffered 8,000 casualties.

Consequently, Frederick was forced to raise the siege of Prague and to evacuate Bohemia.

This battle shows clearly the danger of flank

movements in the presence of an enemy, even when they

happen to be tacticians as bad as the Austrians then were. [5]

The wheel to the right made by the battalion commander

had upset Frederick's battle plan but was not the only cause

of his attack's failure. The failure was more the result of

attempting to move troops under close fire to a flank. The

best troops get demoralized if they suffer from an enemy

close at hand, are directed to ignore it, and make no attempt

to resist.

The battalion commander's reaction was only an

attempt to resist the Austrian skirmishers. The Austrian

light troops (Croats) who disturbed the Prussians appear to

have been unopposed, since Frederick never used

skirmishers. The only prospect of success Frederick's flank

movement could have had was by covering it with a

powerful body of skirmishers, who would attack and

repulse the Croats thus screening his main body while it

moved to the flank.

The King might have attacked the Austrian left, he

was admirably placed for doing so; but to try and march

under a fire of musketry and artillery from an entire army

occupying a commanding position, is to imagine that that

army has neither guns nor small-arms. To say that the

King's maneuver failed because a battalion leader, wearied

with the fire of the Austrian skirmishers, wheeled into line

and attacked in his front is an error. The movement the

Prussian army made was one demanded by the greatest

necessity, - viz., its own safety, and that instinct which

forbids men to allow themselves to be killed without

defending themselves."

The Battlefield Today

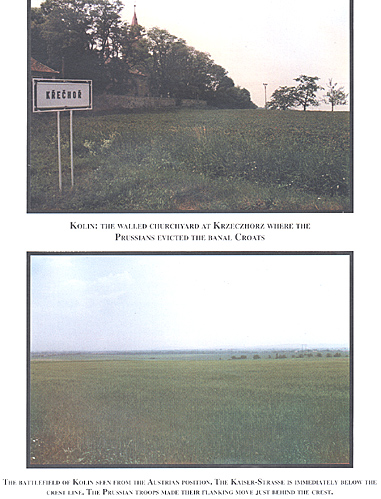

Kolin is located in the Czech Republic some 40

kilometers east of Prague. It is very easy of access. As in

Poland, the German names of towns and villages were

changed back to their original Slavic names (Austerlitz is now Slakov).

Similarly, it would be wise to have with you someone who speaks Czech or at least German (since German is usually spoken by a few people in the villages). The Kolin battlefield has changed very little since 1757.

Frederick's "Oblique Order"

Napoleon made the following comments on the Battle

of Kolin:

Napoleon made the following comments on the Battle

of Kolin:

"At the battle of Kolin, it is difficult to justify the

attempt to turn Daun's right by the flank made from 600

to 1000 yards from the heights occupied by the enemy.

This operation was rash and opposed to the principles

of war. Never make a flank march before an enemy in

position, especially when it occupies the heights at the

foot of which you must march."

Introduction

Prussian Tactics 1757 and the Oblique Order

Battle of Prague: May 6, 1757

Battle of Leuthen: December 5, 1757

Battle of Kolin: June 14, 1757

Conclusions, Notes, and Bibliography

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 4

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com