Frederick's contribution to the art of war was not

limited to battlefield tactics. He and his generals managed

to effect some changes in grand tactical thinking as well.

Frederick rejected the attack along the entire front that had

been accepted as axiomatic by many previous commanders-in-chief and became the advocate of localized attacks. Part

of the Prussian army was to be held back, that is refused

with the main assault being delivered elsewhere.

Frederick's contribution to the art of war was not

limited to battlefield tactics. He and his generals managed

to effect some changes in grand tactical thinking as well.

Frederick rejected the attack along the entire front that had

been accepted as axiomatic by many previous commanders-in-chief and became the advocate of localized attacks. Part

of the Prussian army was to be held back, that is refused

with the main assault being delivered elsewhere.

By 1757, the Prussians had developed the most efficient fighting machine, man for man superior to anything that could be thrown against it. The individual Prussian soldier through incessant, rigid drill discipline, including the cadence step, had become an automaton. Consequently, Prussian units could change direction or front simultaneously or by small groups in succession; they could shift into battle formation from marching column faster than anyone else and vice versa.

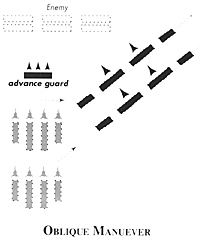

The net result was that the Prussian mobile infantry could be shifted and massed at will on the battlefield as to produce the maximum effect of fire and shock action at any chosen spot. This made possible Frederick's "oblique attack".

The grand tactical ploy of Frederick's "oblique attack" consisted of two techniques: "march by lines" and "attack in echelon". In the march by lines, the Prussians, having already deployed in battle order, would form column quickly by having each division of a battalion quarter-wheel. Minutes later, the entire army would be ready to march around the enemy flank, where it would perform a second series of quarter-wheels to redeploy back into line. Although this tactic had been thought of by many earlier military theorists, the lack of both cadenced marching and the ability to maneuver with closed ranks, had made it impossible to perform a march by lines quickly enough to surprise the enemy.

The attack in echelon consisted of infantry battalions being deployed in a staggered formation, with those on one side further advanced than those on the other. The advantage of this tactic was twofold. First, it made it extremely difficult for the enemy to judge the number of men advancing or their final destination. It also had the advantage of making a change of face (the direction in which the line was facing) much easier to perform. At Leuthen, Frederick used both techniques one after the other to successfully outflank the Austrian left, and this remains the classic instance of the most successful use of the "oblique attack".

It is evident that if troops were to move in this manner, they had to be most carefully drilled. Otherwise, the distances would have been lost and great confusion would have ensued. (The success of the oblique order attack was rendered more and more difficult as the quality of the Prussian infantry drastically declined after 1757-8 because of the huge losses incurred during the Seven Year War.)

Such formations and movements could never take place in the presence of an enemy that could maneuver. In addition, the wheel into line had to be made at considerable distance from the enemy with the result that a long, slow advance in line had to be made under fire. The tactical feasibility of such an advance against powerful artillery was questionable. At Torgau, just barely a Prussian victory, the Austrian artillery destroyed 10 battalions of grenadiers in a few minutes 2.

Even under the leadership of Frederick, such a tricky method of attack was not always successful and became increasingly more difficult to apply as Frederick's enemies made significant advances in the art of war. Some of the main battles in which the "oblique order" was used were Prague, Kolin, Leuthen Rossbach and Torgau. The battles of Prague, Leuthen, Rossbach and Torgau were successful.

At Rossbach, on the morning of November 5, 1757, Frederick of Prussia and his army of 22,000 faced an adversary numbering 40,000 French and Germans. By the time the "oblique attack" was carried out, the Prussian army had swept the enemy from the field. In the process, the Allies lost 10,000 of their troops (killed, wounded, prisoners), while the Prussian losses were only just 548. If Prague and Leuthen were successes, the results were not without casualties'. However, at Kolin, Frederick was unable to take any Austrian positions and the repeated Prussian attacks were repulsed with great losses. At Kolin, the Prussian losses amounted to 12,090 men and 45 guns, while the Austrians suffered 9000 casualties.

In order to further illustrate the "oblique order", we are going to cover three of the battles mentioned above: Prague, Leuthen and Kolin.

Frederick's "Oblique Order"

-

Introduction

Prussian Tactics 1757 and the Oblique Order

Battle of Prague: May 6, 1757

Battle of Leuthen: December 5, 1757

Battle of Kolin: June 14, 1757

Conclusions, Notes, and Bibliography

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 4

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com