Note from Editor: The article on SKIRMISHER TACTICS IN THE NAPOLEONIC WARS, because of its length, will be published in four parts. Part I covers France and England and Part II, Austria; and part III, Russia. Part IV will cover the United States.

Recently I have been repeatedly pressed to present my understanding of Napoleonic skirmish tactics, an understanding which has been slowly drawn together from numerous sources specific to the topic and in some instances, only vague related to the topic. The most frustrating part of trying to track down how Napoleonic skirmishers functioned was that none of the multitude of light infantry drill regulations address skirmish tactics in a major battle. They are fundamentally and uniformly concerned solely with patrols, pickets, and vedettes.

Recently I have been repeatedly pressed to present my understanding of Napoleonic skirmish tactics, an understanding which has been slowly drawn together from numerous sources specific to the topic and in some instances, only vague related to the topic. The most frustrating part of trying to track down how Napoleonic skirmishers functioned was that none of the multitude of light infantry drill regulations address skirmish tactics in a major battle. They are fundamentally and uniformly concerned solely with patrols, pickets, and vedettes.

The fundamental trait in light infantry that distinguished them from line infantry was their training and general usage as skirmishers in battle. The function of skirmishing was the process by which a number of men broke from their rigid formation and deployed into a loose line, and positioned themselves such that they were between the enemy and their lines.

Once deployed in this manner they would fire on any enemy formation that stood before them. The advantage of a skirmish line over a formed line was that it often did not present a target sufficient for a line unit to justify firing a volley at it.

Hitting a Fly

From the perspective of the line it is very much like trying to hit a fly with a table. If the volley hit any of the skirmishers they would be dead, but with the notoriously poor accuracy of the musket and the fact that skirmishers would hid behind rocks, trees, walls, etc., the return for the volley didn't justify firing. Also, once the line had fired, it was vulnerable to a quick rush of cavalry. The risk of perhaps killing a few skirmishers just didn't offset the chance of being hit by cavalry with unloaded weapons. This is why the 1792 Prussian army had the specialized type of fire known as "hedge" fire.

From the perspective of the skirmisher it was very different. His musket was as poor as that of the line infantryman, but it didn't matter. When he shot it was like trying to hit a barn from the inside. His target was so big that he almost couldn't miss. His goal was to position himself such that he could get in a good shot at his target, yet remain under cover of some sort.

Two Goals

Skirmishers had two goals. The first was to engage the enemy's formed units and pepper away at them until their moral was so shaken by the continual effect of seeing people falling around them that they would break when attacked by formed infantry. The second was to deliberately kill the officers and non-commissioned officers of the opponents infantry.

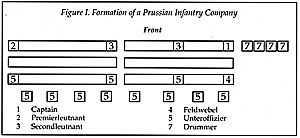

The morale impact of the deaths of the soldiers standing around them was compounded by the deliberate policy of the French skirmisher to aim at the officers and NCO's. Though no published French regulation states that this is the goal, it is obvious from the comments of the Prussians after Jena-Auerst„dt, that this is how the French skirmisher fought. The Prussians reported taking heavy casualties on the ends of their companies. The following illustration of the formation of an infantry company will help clarify what was transpiring. The officers and NCO's were posted on the ends of the company. Even with inaccurate musket shots, the statistical concentration of hits will be in the area where the firing soldier has been aiming.

Figure I. Formation of a Prussian Infantry Company.

Figure I. Formation of a Prussian Infantry Company.

By eliminating those individuals in the formed unit charged with maintaining order as well as controlling the maneuvers of the unit, the skirmishers forced replacements to be drawn from the file closer's rank. When these men were drawn forward into the ranks they were unable to perform as file closers and the ability of men to break ranks and flee the scene of the battle increased. Eventually, the file closers rank would be so depleted that it could not keep men from breaking ranks and running away. Once the company was no longer able to prevent desertions and found itself threatened by a charging enemy, it was doomed to break.

Deliberate

That this was deliberately done is confirmed in a period memoir by Nadezhda Durova, a Russian cavalry officer. Durova's work, The Cavalry Maiden, contains the following passage:

"I asked the captain for permission not to remount"; he agreed, and we went on talking. "Explain to me, Captain, why so many of our officers are being wounded. There is such a dense mass of soldiers that it would be easier to kill more of them. Are they really aiming on purpose at the officers?"

"Of course," answered Podjampolsky. "That is the most effective way of disrupting and weakening enemy forces."

"Why is that?"

"Why? Because one brave, competent officer can do the enemy more harm with his knowledge, sagacity, and skill in using both the advantages of the landscape and the mistakes of the opposing side - particularly when he is an officer endowed with the lofty sense of honor which makes him face death dauntlessly and act coolly no matter how great the danger - such an officer, I repeat, can do more harm to the enemy than a thousand soldiers with nobody to command them."

Two Effects

The functioning of the skirmisher and his fire on the enemy seems to have had two effects. First, they seem to have locked the enemy formation in place, causing it to direct its attention at the skirmishers who were harassing it and distracting it from the formed units advancing behind the skirmishers. In addition, the formed enemy would not be willing to maneuver so as to expose its flanks to the skirmishers. This would permit the forces advancing behind the skirmishers to maneuver at will so as to take advantage of the terrain without the enemy being able to react to those maneuvers.

Various sources indicate that the French skirmishers were quite adept at penetrating larger holes in the enemy battle formation and positioning themselves such that they could fire on the flanks of the forward units.

The second function of a skirmish screen was to protect the friendly forces behind it from the fire of the enemy's skirmishers. This they did by engaging the enemy skirmishers and physically preventing them from approaching the friendly lines.

Tactical Use of Light Infantry

As mentioned earlier, there are very few documents of any type and almost no regulations that speak of the employment and operations of light infantry in battle. Most documents that speak of light infantry tactics dwell on pickets, vedettes or the operations of raiding parties. The following is a compilation of what little information is available on the topic of skirmisher tactics.

As mentioned earlier, there are very few documents of any type and almost no regulations that speak of the employment and operations of light infantry in battle. Most documents that speak of light infantry tactics dwell on pickets, vedettes or the operations of raiding parties. The following is a compilation of what little information is available on the topic of skirmisher tactics.

French Skirmishers

In a Prussian regulation translated for use by the French in 1794 we find the following:

"When the corps of troops is formed in line of battle, or when it must deploy, one ordinarily directs that several detachments be made to cover the wings and front of the troop during the execution of its movement. The officer destined to fill this operation should move forward with his troop, with regards to the part of the formation he is to defend. He should advance himself more or less according to the proximity of the enemy and the advantages provided by the terrain. He shall detach from his flanks tirailleurs who will mask the maneuvers of the formation he is charged to protect. He shall support his tirailleurs according to the circumstances and the strength of his detachment by small troops, each commanded by an officer or sous-officier (NCO)."

"The duty of the tirailleurs is to hold the enemy at a distance by means of their continual fire. If pressed too hard, the tirailleurs shall rally on the small troops destined to support them, while those small detachments attempt to drive back the advancing enemy."

"While the tirailleurs are engaged, the officer in charge shall continually watch the enemy and the force he is to cover. He shall pay particular attention to the unit he is defending so that he may coordinate the movements of his forces and to take successive positions, which favor the formation of the line.

When he hears or perceives the recall signal from the commander of the line he should promptly reassemble his detachment and assure that it resumes its position in the line. If the detached officer was charged with covering a body of cavalry he should not move until the force he was masking is formed, then he should move to the most uncovered or the closest wing. He shall join the attack, covering the flank, and may charge or envelope the enemy as he chooses. If he succeeds in throwing back the enemy he should pursue the enemy rapidly so as to prevent him from rallying and attempt to push him into a route. Those involved in the pursuit should not advance so far that they can no longer be supported by the troop from which they are detached. They should not run the risk of being enveloped as a result of their advancing too far."

J. Colin, in La Tactique et la Discipline spends some time discussing revolutionary skirmish tactics. It would appear that the various battalions detached skirmishers in groups of 30, 50, and 100, depending on the situation. The notorious third rank of each company is specifically called out as being the source of the skirmishers drawn from revolutionary infantry battalions.

He does also state that the newest recruits, those who had had absolutely no training in maneuvers in military formations were simply thrown forward in a skirmish cloud to act as they will. This would indicate that there two qualities of French skirmishing in the early revolutionary wars, good and very bad.

It is interesting to note that Colin contends that the Austrian skirmishers significantly outnumbered the French skirmishers in the early revolution and he states that the Prussians only detached 12 men per company to act as skirmishers.

Deployment

Colin provides an interesting few paragraphs of discussion on how skirmishers were deployed. He states that a peloton or two would be detached to form a skirmish line. He states that they would, upon the order to assume a skirmish formation, move such that there was a 10, 15, or 20 pace space between skirmishers and the alignment was maintained by the eye of the skirmishers.

When the skirmishers were to clear the front, be it to allow the passage of a column or the fire of a battery, they would be ordered to rally on the flanks of their own columns. If threatened they were to move behind their parent formation, which would form into line. Here they would rally and defend the flanks of their parent formation.

Colin quotes de Laub‚pin as saying that the "great bands of skirmishers were not destined to maneuver symmetrically as the lines of battle, the columns or the masses." Their march resembled a loosely organized hunt. If they acted with too much prudence they would be timid and unsuccessful.

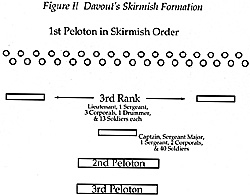

In 1811, Davout issued instructions that provide a great deal of insight into the actual employment of skirmishers by the French. Marshal Davout felt that it was preferable to deploy entire companies as skirmishers rather than subsections of the company. In contrast many German states, Russia, and other countries regularly drew men out of the third ranks of each company to act as skirmishers.

Marshal Davout directed that skirmish lines be formed approximately 100 to 200 paces in front of the formed infantry they were screening. The skirmish formation was organized into three sections. The first and second ranks of the two wing sections deployed immediately by files at intervals of 15 paces and formed a semi-circle of skirmishers 100 paces in front of their parent unit. In each of the deployed sections, the third rank, the sergeant, the corporals and the drummer or bugle were held in reserve with an officer, a lieutenant or sous-lieutenant (2nd lieutenant). The captain remained in the center of this formation with the sergeant-major and the center section. From here he directed the skirmish line. The center section acted as the principal reserve for the skirmish screen.

The reserves were to furnish replacements for the line, to reinforce points where the line was attacked and to provide escorts for officers. This reserves also formed a rallying point and guided withdrawals. The reserve was generally no less than six men. If a non-commissioned officer was detached to carry orders to the skirmishers he was escorted by a fusilier drawn from the reserve.

Figure II Davout's Skirmish Formation

The skirmishers were taught to operate in pairs. One of the two always kept his musket loaded so that he could defend his partner.

When the skirmishers protected a retreating line they formed parallel to that line and withdrew such that their captain could maintain visual contact with the line and his skirmishers. Communications were maintained by using non-commissioned officers as runners.

Trained

The skirmishers were trained to operate at the "pas ordinaire" (76 paces per minute) but they did operate at the "pas de course" (250 paces per minute - a run). This was because they were often obliged to move quickly when covering changes of direction or charges. In the case of a cavalry attack the skirmishers theoretically would retire to their parent unit at the "pas de course" according to regulation, but it is not likely that they worried overly about maintaining a specific rate of movement.

If they were unable to return to their parent unit, they would find whatever cover they could, hiding behind obstacles of any sort and continuing to fire on the attacking cavalry. There was also a "quick" or "rally" square that would be formed. The Austrian equivalent of this formation is the klumpen, which means clump. A sergeant or other individual would stand, calling the men to him and they would form around him in a tight knot of men, all facing outwards. This formation was not capable of significant movement or much fire, but it formed a hedgehog bristling with bayonets that would provide safety for those men that had sought shelter in it.

When advancing, the skirmishers remained silent and attempted to hold the enemy far enough away from their parent unit that enemy fire would not strike it. When operating in broken terrain, it was the mission of the skirmishers to search through all the cover the might conceal any possible ambush.

Marshal Davout's instructions provide considerable insight into the practical employment of skirmishers. If they were to traverse a village the captain would march in the rear, with his reserve, and take an advantageous position that would allow the occupation of the principal avenues, as the skirmishers searched through the village, and to provide a strategically located rally point.

Marshal Davout's instructions provide considerable insight into the practical employment of skirmishers. If they were to traverse a village the captain would march in the rear, with his reserve, and take an advantageous position that would allow the occupation of the principal avenues, as the skirmishers searched through the village, and to provide a strategically located rally point.

If the skirmishers were clearing a woods or passing terrain broken with trenches, hedges, etc., they were to advance cautiously and place themselves such that if they encountered the enemy they were expected to be able to profit from the enemy's errors and force him from his position. The objective being to expose and turn any ambushes. To do this some individuals were expected to seek high points and expose themselves to the enemy, thereby causing the enemy to think that his position was turned.

Because of the system of control and the tactical ability of the skirmishers to profit from the various terrain features, they were able to quickly reinforce a threatened position as well as to deploy quickly so as to take advantage of errors on the part of the enemy. The system that evolved was one where the skirmishers would endeavor to tie the enemy down and allow the formed troops to strike at the enemy's weak point. They succeeded in this by screening the advance of the formed troops, not in the sense that the line wasn't visible, but that the galling effect of the skirmish fire locked the attention of the enemy on the skirmishers, not what was happening behind them.

More Skirmisher Tactics

-

Part I: Intro and French Skirmishers

Part I: British Skirmishers

Part II: Austrian Skirmishers

Part III: Russian Skirmishers

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 14

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com