British skirmish tactics have their roots in the Seven Years War and the American Revolution, but they chopped those roots off when the disbanded nearly every light unit in their army after the American Revolution. In 1798 a work by Rottemberg known as the Regulations for the Exercise and Conduct of Rifles and Light Infantry on Parade and in the Field was published. This regulation formed the basis for all English light infantry operations into the late 19th Century. It draws from earlier experience, but when these regulations were issued in 1798 the wars were already six years old.

Chapter IV addresses firing in extended order and on skirmishing. Rottenberg directs that the skirmishers not have their bayonets fixed when firing in extended order. He also indicates that their movements are controlled by bugles. He also directs that skirmishers operate in pairs, with one always retaining a loaded weapon.

This regulation states that if a light infantry company is sent forward to skirmish each platoon will deploy half of its strength in extended order and engage in skirmish fire. The second half platoon will remain formed behind the skirmish line. He does, however, allow that a company may completely deploy in to skirmish order without retaining a formed reserve.

Chain

This document also speaks of forming a "chain." This was a line of light troops designed to scour a piece of terrain of enemy forces. If a light infantry company were to form a chain, one fourth of it, a platoon or a section, would remain formed. The remainder would form into extended order fifty paces in front of this reserve.

The chain marched at the "ordinary time" taking care to preserve distance and alignment. The reserve followed at a distance of fifty paces. When the chain stopped to fire, it used an unusual firing system. The right wingman of each division would take three paces forward and fire, fall back and load. The next three men would perform the same action singly, and the fire would be kept up until the order to cease fire. If obliged to maneuver to a different front the line was to march at the quick time.

The chain marched at the "ordinary time" taking care to preserve distance and alignment. The reserve followed at a distance of fifty paces. When the chain stopped to fire, it used an unusual firing system. The right wingman of each division would take three paces forward and fire, fall back and load. The next three men would perform the same action singly, and the fire would be kept up until the order to cease fire. If obliged to maneuver to a different front the line was to march at the quick time.

When forming and advanced guard the company broke into four half platoons or sections. The first half platoon moved to the 500 paces front of the main body. At night or in hazy weather this was reduced to 300 paces. The second section was two paces in front of the first and a party consisting of a sergeant and six men was pushed 100 paces further. The third and fourth half platoons were placed 300 paces to the right and left of the first, and even with it, taking care as to preserve their distance from it. They detached a force of a non-commissioned officer and six men 100 paces at an oblique from their front to act as a picket.

Advanced Guard

The duty of the advanced guard was to scour the countryside before the main body, penetrating through woods and enclosures, searching into villages. If the patrol met with an enemy, the officer commanding the half platoons was to inform the company captain who, in turn, sent a messenger back to the battalion commander.

The advanced guard commanding officer was to have been given instructions prior to contact on what his action was to be in such an event. He could attack, withdraw, or merely "amuse" the enemy with his skirmishers. If he were to withdraw he was to do so at an oblique so as to draw the enemy skirmishers away from the front of his battalion so as to clear both himself and the enemy skirmishers away from the front of his battalion and give it a clear field before it.

When ordered to close, the outer sections and the detachments closed on the central section. What actions were to be taken then are not specified, but it is presumed that the skirmishers would return to their parent battalion. Unfortunately, no comment is made about actions to be taken in the event of attack by cavalry when in skirmish formation.

Captain Cooper's work provides a summarization of the skirmish tactics in use by the English in 1806. Among the many details he provides, there are some unique notes on the differences in intervals in the "formed" line. I say "formed" because the process he describes moves it from the tightly compressed line to a skirmish line in a very regulated manner.

Cooper first discusses "loose files" which was when the infantry company opened their ranks such that there was a six inch gap between each man. Open order, he defines as having further widened this gap between each man to a distance of two feet. The largest interval, extended order, he defines as being two paces between men in rank.

At this point it is worth a historical digression and some analysis. When formed in line the average infantry man occupied about 22 inches. If one assumes two paces as being approximately six feet a line of infantry going into extended order would increase its length by about 300%, but its density would not appear as thin as a French skirmish line. Indeed, it might well appear to be a formed line if not examined too carefully.

In his introduction, Cooper says that "in the open plain, they can act as a compact body,.." which suggests that they were likely to be in "extended order," but could also be referring to the use of light infantry in the traditional linear mode. This is, of course, substantiated by Rottenberg's work, which clearly states that they were in extended order.

Understrength

Understrength

As mentioned earlier, the British battalions were notoriously under strength. A full strength battalion (1,000 men) deployed in a two deep line would form a line 916 feet long. The average battalion had something less than 660 men, which would give it an interval of 605 feet. A one hundred man company, the standard detachment of skirmishers for the British, would occupy an interval of 189 feet in open order. It is, therefore, quite possible likely that the French might well perceive a British skirmish line in extended order as a formed line.

This takes several steps towards explaining why, in Spain, the French often thought that they had broken the first English line when, in fact, they had only pierced the British skirmish line. Though it does not provide much insight into Oman's theories on the effect of the line on the attacking column, it does begin to suggest some of the process that was actually occurring.

Cooper points out that in open order the officers were in front of the company and in extended order the officers and NCO's were behind the line. In extended order the British infantry still apparently could and did fire vollies. They operated in pairs, one holding his fire while the other reloaded.

Though Cooper does not provide a reserve of "regulated" strength as did the French and other nations, he does clearly state that a "considerable portion of their force should at all times be kept in reserve." He also states that the men deployed in the skirmish line were to be supported by "small parties a little to their rear; and these again should depend upon, and communicate with stronger bodies, further removed from the point of attack." He does, however, diverge from the French in that he says that these reserves should be concealed from the enemy.

In contrast to Cooper's rather vague statement, Barber's 1804 treatise on skirmishing states that "it is a rule that one half of the company remains formed as a reserve; but when acting under the support of another corps, the whole may skirmish."

Barber adds some interesting notes on the system the British skirmishers used in case of cavalry attack. All of the soldiers apparently fired and, "every man makes the best of his way round the flanks (of the battalion) to the rear or through any opening in the line." It sounds like a rather uncoordinated scramble to the rear.

Barber adds some interesting notes on the system the British skirmishers used in case of cavalry attack. All of the soldiers apparently fired and, "every man makes the best of his way round the flanks (of the battalion) to the rear or through any opening in the line." It sounds like a rather uncoordinated scramble to the rear.

As in Davout's instructions, Barber and Cooper both allow that British skirmishers could and should take advantage of any cover, and that they should be able to fire standing, kneeling or lying down.

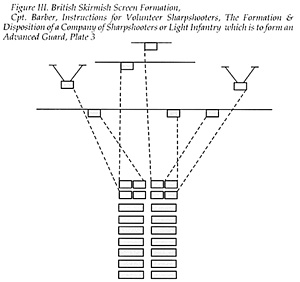

Barber places his advanced guard skirmish lines 300 to 500 paces in front of the line, based on weather and visibility. He states that a second section "is detached 200 paces in front of the first, and a party of a sergeant and six men is pushed on 100 paces further, which forms the head of the advanced guard. The third and fourth half platoons are placed 300 yards to the right and left of the first, and when even with it, taking care to preserve as much as possible the above distance from it; and detaching 100 paces forwards, and in an oblique direction to the outer flank, a non-commissioned officer and six men."

In stark contrast to Cooper's wild scramble away from attacking cavalry, Barber speaks of a hollow square. The reserve closed with the skirmishers, "they, being the second section, form front as quickly as possible, and the remaining sections complete the square." Though very brief, this sounds very much like the system described by Major General Winfield Scott in his manual of infantry tactics.

Figure III. British Skirmish Screen Formation, Cpt. Barber, Instructions for Volunteer Sharpshooters, The Formation & Disposition of a Company of Sharpshooters or Light Infantry which is to form an Advanced Guard, Plate 3

Figure III. British Skirmish Screen Formation, Cpt. Barber, Instructions for Volunteer Sharpshooters, The Formation & Disposition of a Company of Sharpshooters or Light Infantry which is to form an Advanced Guard, Plate 3

In actual execution, the British drew the light companies from their line battalions, in every division. They then combined these light companies with companies of the 5/60th Regiment of Foot and the Brunswick Oels, forming ad hoc light battalions that deployed before the line infantry. Thus, the battalions of light infantry spoken of by Barber and Cooper were formed and ready to function.

Bibliography

Barber, Cpt., Instructions for the Formation and Excercise of Volunteer Sharp-shooters, 1968, Ottawa, Museum Restoration Service.

Colin, J., La tactique et la discipline dans les armees de la Revolution; correspondance du General Schauenbourg du 4 Avril au 2 Aout 1793, 1902, Paris, Librairie Militaire R. Chapelot et Cie.

Cooper, Cpt. T.H., A Practical Guide for the Light Infantry Officer Comprising Valuable Extracts from all the most Popular Works on the Subject; with further Originial Information: and Illustrated by a set of Plates, on an Entire new and Intelligible Plan; which Simplify Every Movement and Manoeuver of Light Infantry, 1970, London, Frederick Muller Ltd.

Duhesme, Essai sur l'infanterie legere ou Trait‚ des petites op‚rations de la Guerre, 1864, Paris, J.Dumaine, Librairie-Editeur de l'Empereur.

Durova, N., The Cavalry Maiden, Journals of a Female Russian Officer in the Napoleonic Wars, 1988, London, Angel Books.

Grossen Generalstab Kreigsgeschichteliche Abteilung II Deutschland, 1806, Das Preussische Offizierkorps und die untersuchung der Kreigsereignisse, 1906, Berlin, K"niglich Hanbuchhandlung.

Magueron, Campagne de Russie, 1897-1906, Paris, Henri Charles-Lavauzelle.

Rottemberg, Regulations for the Exercise and Conduct of Rifles and Light Infantry on Parade and in the Field, 1798, Whitehall.

Scott, Maj. Gen. W., Infantry Tactics; or, Rules for the Exercise and Manoeuvers of the United States' Infantry, 1861, New York.

Valentini, Abhandlung ober den Kleinen Krieg und uber den Gebrach der leichten Truppen, 1820, Leipzig.

Drill Regulations:

Austrian - Exercir-Reglement fur die Kaiserlich-kniglich Infanterie , 180, Vienna,.

British - Regulations for the Exercise and Control of Rifles and Light Infantry on Parade and in the Field, 1798, London.

French - Instruction pour le service et les manoeuvres de l'Infantirie legere, Date unknown (probably 1805-1808), Paris.

French - Instruction destin‚ aux troupes legere et aux officiers, Date and publication unknown (probably 1805-1808).

French - Instruction destin‚ aux troupes legeres et aux officiers qui servant dans les avant-postes, redigee sur une instruction de Frederic II … ses officiers de cavalerie, date unknown, Paris, 4th edition.

Hesse-Kassel - Instructions for samtliche Infanterie-Regimenter und das Fusilier-Bataillon, 1797, Kassel, Handwritten document.

Prussian - Reglement fur die K"nigl. Preuss. leichte Infanterie, 1788, Berlin.

Zweguintzov, W., L'Armee Russe, 4th Part, 1801-1825, 1969, Paris, Privately Published.

More Skirmisher Tactics

-

Part I: Intro and French Skirmishers

Part I: British Skirmishers

Part II: Austrian Skirmishers

Part III: Russian Skirmishers

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 14

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com