Part 1: The Sultan's Big Guns

Part 2: The Pasha's Big Guns

In parts one and two of this series we looked at the Ottoman Imperial artillery and the artillery forces of the various provincial governors during the Napoleonic Era. In this last installment we wrap up our look at Ottoman artillery with the Ottoman mortar corps and various related units.

Allied with the Topijis (the Imperial field artillery)

was the Humbaraci (the Imperial mortar corps).

Allied with the Topijis (the Imperial field artillery)

was the Humbaraci (the Imperial mortar corps).

Originally drawn from the feudal forces, like much of the army, the Humbaraci had been allowed to deter riorate over time. When Selim III came to the throne in 1789 it existed in name only.

Starting in 1792 a strenuous effort was made to revive the corps with the assistance and advice of the French artillery experts Aubert and Cuny. An entirely new force was recruited.

As with the Topijis, most of the Humbaraci recruits came from Bosnia, often from among former bandits who sought to better themselves through service to the Sultan. A large number of Albanians, many of them former Sipahi cavalry, were also recruited into the new corps. New barracks, stables and storehouses were built for them.

New Organization

The new organization of the mortar corps was laid out in the spring of 1793. The force was organized into five units, consisting of four units of 10 mortars each and a fifth unit of 10 Abus cannons.

Each of the four mortar units was equipped witn more tars of a different caliber with the first unit equipped with mortars of a 65-centimeter diameter; the second, 36 centimeters; the third, 22 centimeters, and the fourth, 14 centimeters. The Abus unit was equipped with five guns of seven centimeter diameter and five guns of 10centimeter diameter. The Abus guns were similar in design to Russian licornes.

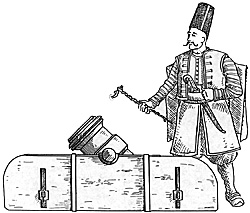

The mortars were loaded on wagons (at right) to be moved into battle. Once unloaded for firing they were immobile.

The mortars were loaded on wagons (at right) to be moved into battle. Once unloaded for firing they were immobile.

As with the Topijis, each gun was manned by a single squad which took great pride in the maintenance and performance of its personal gun. The mortar corps was considered an elite force and both officers and men were prohibited from marrying. The reason for this was so the men could remain in their barracks at all times to be subjected to the strict discipline and prolonged training needed to maintain their high standards. In recognition of their skill, and because of the dangerous and difficult nature of the service, Humbaraci gunners received numerous special benefits, including double the normal pension.

Each 10-gun battery was commanded by a Ser

Halife. Each gun was operated by a squad of nine cannon

men (Humbaraci) and one officer (Halife) who were

assisted by nine orderlies (Mulazim). Unlike the Topijis, the

mortar corps was responsible for transporting its own guns.

Each 10-gun battery was commanded by a Ser

Halife. Each gun was operated by a squad of nine cannon

men (Humbaraci) and one officer (Halife) who were

assisted by nine orderlies (Mulazim). Unlike the Topijis, the

mortar corps was responsible for transporting its own guns.

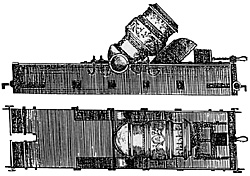

At right, a top and side view of an Ottoman mortar. This model is slightly smaller than the one pictured at the beginning of this article, measuring only six feet from front to back. All the illustrations with this article are taken either directly or redrawn from Mahmoud Rayf Efendi's 1798 book "Tableau Des Nouveaux Reglemens de L'Empire Ottoman."

Two men in each gun crew were responsible for the loading and transport of the gun. The guns were loaded on wagons and two beasts of burden were assigned to each wagon.

The corps was headquartered in Haskoy and Sutluce on the north shore of the Golden Horn in Istanbul.

The members of the corps were required to drill with their weapons daily except Tuesday and Friday during the summer. In winter they studied mathematics and conducted theoretical training. All members of the corps were required to learn to fire mortars, cannons and muskets. They also were trained as engineers, leaning to construct fieldworks, dig trenches, build bridges and perform other such tasks.

Because of the Sultan's personal interest in the force, its intensive training and high pay, the Humbaraci were considered to be of guard status.

Allied with the Imperial artillery forces were a number of other corps including the transport corps and the engineers.

| Organization of the Humbaraci Corps | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company Number | Caliber of guns in Company |

Number of Guns | Number of Ser Hafites |

Number of Hafites | Number of Humbaraci Men |

Number of Orderlies | Total Men |

| 1 | 65 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 90 | 90 | 191 |

| 2 | 36 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 90 | 90 | 191 |

| 3 | 22 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 90 | 90 | 191 |

| 4 | 14 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 90 | 90 | 191 |

| 5 | 7/10 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 90 | 90 | 191 |

| Sub total | 50 | 5 | 50 | 450 | 450 | 955 | |

| 5 Senior Officers | 5 | ||||||

| Corps Total | 960 | ||||||

| From Dr. Stanford J. Shaw's article THE ESTABLISHED OTTOMAN ARMY CORPS UNDER SULTAN SELIM III (1789-1807) | |||||||

LAGIMCIYAN

The commander of the Humbaraci corps was also commander of the Lagimci (miners) corps, or Lagimciyan. The Ottomans inherited the highly sophism ticated siege- engineering tradition of Islam and expanded on it still further. Ottoman siege craft was considerably ahead of any European capabilities, and reached a level of sophistication not equaled in Europe until the First World War.

Their engineers, called Lagimcilars, designed the works and supervised unskilled laborers and conscripted miners plus whatever troops were available. Ottoman trenches were deeper and broader than those in Europe, with fire-steps and sandbag or turf embrasures. The low working chambers in which Ottoman miners dug, sitting cross-legged, made their explosive mines even more effective.

Under Selim III the force numbered about 1,000 men and was divided into two main divisions. The first specialized in the science and techniques of preparing and laying mines. The second was an engineering group in charge of military architecture, building forts, bridges, trenches, batteries and the like. Both groups received intensive mathematical training.

In 1794 two new barracks were built in Haskoy near those of the mortar corps to house 200 men and 50 ape prentices of the corps. The direction of its military and technical activities was left to the Lagimci Bashi who also cooperated with the supervisor in administration and financial functions.

Because of the importance placed on defensive tactics by the Ottomans, engineers and sappers always ace companied the army in the field. They supervised the construction of quick but effective fieldworks, and even large wooden fortresses, called Palankos, complete with watchtowers and cannon emplacements. These Palankos were often built to guard potential bottlenecks during the advance or to provide secure storage depots.

The efficiency of this force was further increased because the Janissaries were skilled builders. It was traditional for the Janissary forces in the capital to spend the winter months working on public works projects, providing each man with extensive hands-on experience. The Ottoman army also contained a number of mobile bridging units, using a pontoon system similar to those employed by most European powers.

After the destruction of the Janissaries in 1826 both arms of the Lagimciyan remained in existence, the only change being the addition of a single white vertical band to their long black cylindrical bonnets.

ARABACIYAN

While the Topijis were responsible for operating their guns in battle, it was the job of the Arabaciyan, or cannon-wagon corps, to maintain the cannons and transport them to the conflict. Both by origin and function, this corps was auxiliary and subordinate to the cannon corps, but by tradition it maintained an independent organization with separate regulations and of ficers. The Arabaci cared for the transport and maintenance of the Topijis corps cannons and for the animals and wagons provided by the state.

Like the Topijis, the force underwent a near total reorganization in 1793. A month after the official declaration reorganizing the artillery corps in April 1793, the same sort of reform was extended to the allied cannonwagon men.

One result of the new regulations was that the position of cannon-wagon supervisor was joined to that of cannon corps supervisor, thus uniting the administrative and financial operations of the two groups. The force underwent rapid growth to keep pace with the increase ing needs of the cannon corps. Starting with a force of 600 men in 1793, it quickly expanded, reaching a total of 2,129 men in 1806.

The corps was organized into five Ortas, the first led by the corps commander and therefore know as the Agha Ortasi. The second was led by the commander's lieutenant and was known as the Kethoda Ortasi. Five Arabaci men and one cannon-wagon were assigned to each Topijis cannon along with a wagonmaster (Arabachi Halife) who served as unit commander. The men assigned to each cannon wore the same cannon insignia badge as did the Topijis officers and men assigned to the gun.

Additionally, each Orta was assigned a special contingent of four carpenters, two locksmiths, two saddle makers and four blacksmiths to care for the various jobs associated with the maintenance of the horses and wagons. Each Orta also had a unit of l0 orderlies headed by a Bas Qolluqcu, which was assigned to assist the officers of each regiment and provided a pool of trained replacements to fill vacancies.

In addition to its various forms of field artillery, the Ottomans maintained fortresses and garrisons throughout the empire. The most important of these were the naval forts defending the capital and the chain of fortresses along the Danube.

Coastal Forts and Danubian Fortresses

The Ottoman Artillery Series

Back to Dragoman Vol. 2 No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Dragoman List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by William E. Johnson

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com