In our Fall 1996 issue we looked at "The Sultan's Big Guns" which covered the Ottoman Impenalfield ariillery of the Napoleonic Era. In this issue we will look at some of the other artillery forces available to the Ottomans, including their mounted ariillery and provincial forces.

The Ottomans loved artillery of all kinds. We have already looked at their field guns. Now let's look at the rest of the Ottoman artillery arm.

When Mahmud II became Sultan in 1808 he

lavished special attention on a small unit of mounted

artillery then in existence. He secretly built up its strength

until it eventually totaled 1,000 men serving 70 light f~eld

pieces. Attached to the unit were 60 teams of transport

men.

From its very inception, the unit was fully

Westemized in equipment, drill and tactics. As with other

Ottoman artillery units, each battery consisted of 10 guns.

All members of the force were mounted and each gun was

served by 12 men instead of the usual 10 because two men

were assigned to hold the horses.

Although the force was routed and largely

destroyed by the Russians in 1812, it was subsequently

rebuilt and provided the Sultan with a well-trained, well-

paid and loyal force as part of his personal guard. It was

the unflinching support of this regiment in June 1826

which was the major cause of the Sultan's victory over the

Janissaries.

The 1,000-man figure for the unit represents its

strength in 1826 at the time of the last Janissary rebellion.

No accurate figures for its strength during the

Napoleonic Era are available. However, there was at least

one 10-gun battery in 1808 and at least several other

batteries were added by the end of the War of 1806-1812.

While I have no information on gun calibers, it is a safe

assumption that it, like all of the new artillery being

introduced in this period, was based on the French model.

There is evidence that some of the provincial

governors also maintained batteries of horse artillery.

In 1814, in a conversation with J.L. Burckhardt,

Mohammad Ali, Ottoman governor of Egypt, proposed

defending Egypt against an anticipated English invasion by

using his cavalry and horse artillery to conduct a scorched

earth policy married to a hit-and-run campaign. Mark

Bevis, in his book, Tangiers to Teheran, lists two

Egyptian horsegun batteries in his army listing for

Mohammad Ali in the 1807-1815 period, each of six 3 -

pounders. In a private letter he says these units were raised

about 1808- 1809.

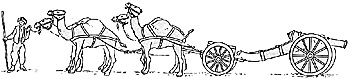

Artist's conception of a unit of camel artillery. The sketch is based on a small detail from a French painting of the Battle of Abukir Bay. The harness and hitching are assumptions by the artist as the painting has insufficient detail.

The use of camel-mounted guns had been

common in the Ottoman Empire in earlier times, but by the

Napoleonic Era no such units remained in the Imperial

army. Nonetheless, the evidence is quite strong that these

guns remained in service in other parts of the empire,

especially around Arabia

In 1814, when Burckhardt was visiting Mecca, he

watched the arrival of the pilgrimage caravan from

Damascus and remarked that "Among the troops of

Suleyman Pasha, about 60 Zamburaqs attracted notice:

These are artillerymen, mounted on camels, having a small

swivel before them, which turned on a pivot faced to the

pommel of the camel's saddle. They fire while at a trot,

and the animal bears the shock of the discharge with

great tranquility. Would later write, "The practice of

mounting upon camels small swivel-guns, which turn upon

the pommel of the saddle, is not known in Egypt. I have

seen them in Syria; and they appear to be common in Mesopotamia and Baghdad. Although of little real service, yet against Arabs these small swivel-guns are a very excellent and appropriate weapon, more adapted to inspire them with terror than the heaviest pieces of

artillery." In his army list for Syria, Bevis lists these guns as one-pounders.

The use of such camel guns had long been

common in the Persian Gulf region with both Persia and

many of the various Indian states using them. The Persians

were especially proud of their camel guns, even including a

unit of them in their guard force.

Artist's conception of a Zamburaq at right. Ammunition bags are hung at the front of the camel and a water skin is slung underneath. Drawing by Joshua Shepherd.

In 1809 James Morier, attached as secretary and

translator to the British mission to the court of the Shah,

witnessed a demonstration of these guns which he said

were made of brass.

"The state elephants were on the ground, on the

largest of which the King, seated in a very elegant howdar,

rode forth from the city. When he alighted he was saluted

by a discharge of the Zamburaqs, the salute indeed is

always fired when the King alights from his horse or

mounts. In one of the courts of Shiraz we had previously

noticed this artillery.

The Zamburaq is a small gun mounted on the back

of a camel. The conductor from his seat behind guides the

animal with a long bridle, and loads and fires the little

cannon without difficulty. He wears a coat of orange-

colored cloth, and a cap with a brass front; and his camel

carries a triangular green and red flag. Of these there were

100 on the field; and when the salute was fired they

retreated in a body behind the King's tent, where the

camel~s were made to kneel down. Collectively they made

a fine military appearance. This species of armament is common to many Asiatic states, yet

the effect at best is very trifling. The Persians, however,

place great confidence in their execution; and Mirza

Shefeea, in speaking of them to the Envoy, said, 'These are

what the Russians dread."'

While such camel guns were becoming increasingly

rare by the time of Napoleon, the use of camels, in place of

horses, to haul artillery, was common throughout the

Ottoman Empire.

The Mamluks are said to have had 10 camel-drawn

batteries of artillery which they used against Napoleon

during his invasion of Egypt in 1798. Most of these guns

were captured in the early stages of the campaign and some

were incorporated into the French army. If you look closely

at the famous painting of Napoleon's victory over the

Ottomans in the Battle of Abukir you will see such a battery

of French artillery being drawn by a team of four camels.

Other European powers were equally aware of the

usefulness of camel-drawn artillery in the Middle East. As

an inducement to declare war on France at the time of

Napoleon's invasion of Egypt, the British presented the

Sultan with 12 brass six-pound cannons especially fitted out

for camels. The Sultan is said to have been delighted with

the present and immediately sent these guns to the front.

In addition to the artillery forces of the Imperial

army, the local govemors maintained their own artillery

units. Pasvanoglu, Pasha of Vidin, had more than 60 field-

guns and a large contingent of siege guns. While

occasionally quite numerous, these provincial batteries were

usually composed of slow, bulky, obsolete guns totally

unsuited for mobile battlefield use. Nonetheless these guns

could be quite useful and deadly if installed in fortresses and

fieldworks, as the Russians, with their tendency to charge

the Ottoman defenses, found on many occasions.

In the Balkans, especially in Bosnia and Albania,

there was also a good number of the newer French guns.

Of these most were supplied by General Auguste Marmont

from the French supplies in Dalmatia. The guns, amounting

to many dozens of pieces of artillery, always came with

French advisers to teach the local gunners to operate the

guns in the French manner. In more than a few cases, the

guns came with entire French gun crews. French artillery

units served on and off with Ali Pasha of Janina and with

the Bosnian forces against both the Russians and the

Serbians from 1804 to 1808.

There was also a fair number of modern artillery

pieces in Greece supplied by the Russians. The Russians

supplied the guns to support the Greek independence

movements and to build up the armies of the local notables

who opposed Ali Pasha. Throughout this period Ali Pasha

dreamed of carving out his own kingdom in Greece and the

Balkans and as such, he was a constant threat to Russian

efforts in Montenegro, Serbia and the Ionian Islands.

On the eastern end of the empire the incessant

Russian wars with both the Ottoman and Persian empires

over Georgia allowed a fair number of Russian artillery

pieces, and through desertions and prisoners of war, Russian

gunners, to fall into the hands of the Ottoman notables. By

1805 Tayyar Pasha, the governor of Erzurum, had assembled

at Sinop a large force of Europear-style artillery led by

Russian deserters.

By far though, the greatest provincial artillery force

was assembled by Ali Pasha of Janina. Ali had a passion

for artillery. By 1815 he had more than 200 pieces of

artillery, much of it stolen from other Pashas. A goodly part

of it, though, was supplied by first the French and then the

British who were both vying for his favor to support

their actions in the adjacent Ionian Islands.

To keep his artillery force at its peak, Ali Pasha

established an artillery school near Janina and from 1798 on

always employed a European officer as the head of his

artillery.

In 1809 the British began supplying Ali Pasha not

only with artillery and mortars, but with units of Congreve

rockets. While they were intended for use against the

French, Ali put them to use suppressing a Greek uprising and

then turned them on his old enemy, Ibrahim Pasha of Berat.

As Ali's forces, led by his son Muhtar, saw

extensive action against the Russians along the Danube

during the War of 1806-1812, some of these rockets may

have also been used against them. The supply of rockets (or their local manufacture) must have remained constant for even after years of use against his enemies, Ali was still

able to fire great barrages of rockets at the besieging

Ottoman forces which ousted him from his Pashalik in 1820-

1821.

Whether other Ottoman commanders used

rockets is unknown. What is known is that in 1784 Sultan

Tipu of India sent a mission to the Ottomans and among his

gifts were a number of Indian military rockets which created

a sensation among the Ottomans. And there is a reference

in Uthman ibn Bishr's history of the Wahhabi Wars in

Arabia which says the forces of Mohammad Ali used a

form of rocket during the siege of the Wahhabi capital of

Dariye in 1818.

In the next installment in this series we will once again return to the Imperial army and look at the Ottoman mortar corps, fortress artillery and combat engineers.

The Ottoman Artillery Series

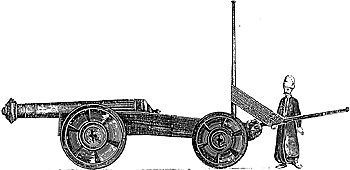

At right, an Ottoman great cannon with an old style limber, taken from Mahmoud Rayf Efendi's 1798 book, Tableau Des Noweaux Fleglemens de L'Empire Ottoman. We have added the man to

provide scale.

At right, an Ottoman great cannon with an old style limber, taken from Mahmoud Rayf Efendi's 1798 book, Tableau Des Noweaux Fleglemens de L'Empire Ottoman. We have added the man to

provide scale.

HORSE ARTILLERY

CAMEL

ARTILLERY

While the Ottomans probably possessed no horse

artillery until about 1808, they might have had several units

of camel artillery.

While the Ottomans probably possessed no horse

artillery until about 1808, they might have had several units

of camel artillery.

While we don't have any description of the

Ottoman camel guns, we do have a description of the

Persian guns of this period which were probably very

similar.

While we don't have any description of the

Ottoman camel guns, we do have a description of the

Persian guns of this period which were probably very

similar.

PROVINCIAL

ARTILLERY

ROCKET

ARTILLERY

Back to Dragoman Vol.1 No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Dragoman List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by William E. Johnson

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com