The Ottomans were among the very first European powers to introduce artillery into their armies.

During the Napoleonic Era they maintained a large artillery force both in the Imperial anny and in the various local armies of the provincial governors.

The Ottomans were among the very first European powers to introduce artillery into their armies.

During the Napoleonic Era they maintained a large artillery force both in the Imperial anny and in the various local armies of the provincial governors.

The artillery arm of the Capou-Koulis, the Ottoman Imperial army, was known as the Topijis and was the only part of the army which welcomed Sultan Selim III's attempts at modernization. They readily accepted French training and weapons from the advisers Selim imported. At the time of Selim's death in 1808 the Topijis corps numbered 5,121 troops.

In 1793 Selim appointed his close friend and adviser, Mustafa Reshid Efendi, as supervisor of the Topijis and the Imperial foundry (Tophane-i Amire) and powder works (Baruthane). Under Mustafa the barracks and training grounds of the corps, located in the Tophane section of Istanbul, were enlarged and modernized. To assist the corps, European artillery officers, under the direction of the French officers Cuny and Aubert, were assigned to each unit.

Reorganization

Selim reorganized the 23 existing artillery regiments and added two more for a total force of 25 units, each with a total complement of 115 officers and men. He also ordered the adoption of the Prussian drill system. About half of these regiments were stationed in and around Istanbul with the rest in the provinces.

To weed out corruption and incompetence a severe examination was given to all existing members of the corps and only 10 percent were found fit for service. The rest were dismissed and new men, mainly &om the province of Bosnia, were enrolled.

The expansion of the corps went ahead rapidly and by the end of 1796 there were 2,875 well- trained cannoneers stationed at the Tophane along with an additional company of 115 men stationed at Levend Chiftlik to assist the new Nizam-i Jedid army. In 1806 the force numbered 4,910 men who were reputed to be by far the ablest fighting men among the old established corps.

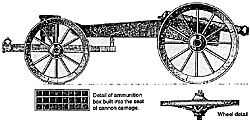

Pictured at the beginning of this article is one of the older, slower Ottoman field guns known as Sahis. All the illusrations for this article are either taken directly, or redrawn from Mahmoud Rayf Efendi's 1798 book, Talleau Des Nouveaux Reglemens de L'Empire Ottoman.

Topiji Bashi

The entire force was under the direction of an

officer known as a Topiji Bashi. His authority over the

corps was absolute, not only in Istanbul, but in all the

fortresses and garrison towns of the empire, which he

supplied with artillery stores and ammunition. He was also

head of their respective magazines.

Each regiment of foot artillery was made up of l0

cannons; four of the older, heavy Balyemez and Sahi

cannons, two of the older, lighter Abus guns and four of the

new French-designed field guns, identical in size and design

to the guns then in use in the French army.

The terms Balyemez, Sahi and Abus were the

names of the various classes of guns, each of which came

in a bewildering range of sizes.

The Balyemez were massive, long-range guns--

what Europeans would think of as siege artillery. They

came in sizes ranging from 60- to 120-pounders or more.

Sahi was the Ottoman word for "f~eld," and therefore Sahi

artillery meant simply field artillery. They came in sizes

ranging from 4-pounders to 14-pounders. The Abus guns

were a form of howitzer and came in 10- and

7centimeter diameter bores. The French-design guns were

known as SuratTopcusu (speed artillery) because of their

greater mobility.

It was reported in 1793 by a French military

observer that "the Turks have founded only bronze cannon and their

army and navy have no other." It is therefore assumed that

all the Balyemez, Sahi and Abus cannons were of bronze.

One Boluk (squad), usually consisting of l0 men,

was assigned to each gun. Each gun was given its own

special sign or mark which was painted on the muzzle and

sewn on the uniforms of the men assigned to it. With the

exception of this painted design, Ottoman guns were as plain

as possible, without the least omament.

The best gunner in each Boluk was appointed as

cannon master (Top Ustasi) and the next ablest as his

assistant (Yamaq). The l0 cannon masters in each regiment

were arranged in a numbered hierarchy from one to l0, with

the first cannon master commanding the others during

battle. Each regiment was also assigned 30 orderlies

(Mulazim) who assisted the regular soldiers and replaced

them when vacancies occurred.

Since the older Balyemez and Sahi cannons were extremely heavy and bulky, they were usually kept in trenches some distance from the actual fighting. However the new French guns and the lighter Abus guns were quick enough to keep up with the infantry and were often placed

in the thick of battle.

This, naturally, resulted in increased casualties so in 1796 each battery was assigned an additional 20 soldiers whose job was to defend the guns in the field. While they were primarily riflemen, they were also cross-trained as artillery men so they could take over for dead or disabled gunners.

Practice

To keep the units in top form, they were required to

practice once each week with live ammunition. British

military observers, watching one of these artillery practice

sessions in Istanbul in 1799, were impressed with the Topijis'

skill.

Commenting on the practice, a member of the British artillery unit remarked that, "The artillery-men succeeded much better than our officers had been led to expect. The Turkish artillery-men beat down the target several times, and their mortar practice was by no means contemptible." This is fair praise considering that the British were considered among the best gunners in the world at this time.

While the Topijis were well trained and enthusiastic, their performance as gunners remained poor during the period due to the erratic quality of the inferior gunpowder with which they were supplied.

While not as prone to overturn them, the ariillery corps--as did the armorers, mortar corps and engineers--possessed a number of brass kettles which were considered sacred to the unit.

More Big Guns

The Ottoman Artillery Series

At right, pictured is one of the new French-designed guns introduced into the Ottoman ammy in the 1790s. These were known as Surat Topcusu, or speed artillery, because of their high mobility. This gun measured about 10 feet from the tip of the barrel to the end of the trail. Detail of ammo box built into the seat of the cannon carraige at left, wheel detail at right.

At right, pictured is one of the new French-designed guns introduced into the Ottoman ammy in the 1790s. These were known as Surat Topcusu, or speed artillery, because of their high mobility. This gun measured about 10 feet from the tip of the barrel to the end of the trail. Detail of ammo box built into the seat of the cannon carraige at left, wheel detail at right.

Back to Dragoman Vol.1 No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Dragoman List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by William E. Johnson

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com