The Alamo Part 1 The Mission San Antonio de Valero

The Alamo Part 2 The Mexican Army

In this third article the focus will be on the Texan Defenders who stood upon the walls of the Alamo mission during that famous 13 day siege.

We have all seen John Wayne portraying Davy Crockett in the 1960's epic movie "The

Alamo". Since then there have been numerous other depictions of this famous

event and a new version hits the big screen in Christmas Day, 25 December

2003. One can hardly discount that the gallantry, courage and sacrifice of

those 189 men (some say 185 men) played a major role in Texas gaining her

independence. "Remember the Alamo" is as much a part of the America fiber

as any other gallant stand prior to or since that early morning of 6 March

1836. Regardless of their reasons for standing on those battered walls, and we

are not here to debate them, their tenacity, courage and fighting spirit has

survived to this day in America's own service men and women in uniform.

They are all of the same mold. But who were these Texans and where did they

all come from? Specific to the Alamo siege, let's take a look.

We have all seen John Wayne portraying Davy Crockett in the 1960's epic movie "The

Alamo". Since then there have been numerous other depictions of this famous

event and a new version hits the big screen in Christmas Day, 25 December

2003. One can hardly discount that the gallantry, courage and sacrifice of

those 189 men (some say 185 men) played a major role in Texas gaining her

independence. "Remember the Alamo" is as much a part of the America fiber

as any other gallant stand prior to or since that early morning of 6 March

1836. Regardless of their reasons for standing on those battered walls, and we

are not here to debate them, their tenacity, courage and fighting spirit has

survived to this day in America's own service men and women in uniform.

They are all of the same mold. But who were these Texans and where did they

all come from? Specific to the Alamo siege, let's take a look.

Texan Leadership

General Sam Houston had ordered Colonel Jim Bowie to "blow-up" Alamo and to move the guns to Goliad. However, as we now know, this order was not followed. Sam Houston was aware that the Alamo was far too large to be defended and that it served no tactical value as a blocking element to Santa Anna's advancing army. Yet, in defending it, the Alai-no became a battle cry that in, resulted in hundreds of Texans and Americans rallying to a common cause that eventually made Texas free.

James Bowie, the legendary 40-year old knife-fighter and native of Georgia, had made a fortune in the slave market when he moved to San Antonio 1828. He like the place so well that he married Ursula Vermendi, built a large villa and became a land speculator. By 1832 he had acquired over 750,000 acres of Texas land and had become one of the most respected citizens in San Antonio. A year later Jim Bowie's wife and two children died in a cholera epidemic and he took to drinking heavily. It was during this period that he became actively involved in a movement that advocated the separation of Texas from Mexico.

There can be no doubt that the prospect of acquiring more land and gaining even more personal wealth played a major role in his decision to align himself with those that sought to make Texas an independent and self-governing Republic. His decision to defend the Alamo against over-whelming odds, even when he was sure he would not survive the ordeal, however, indicates a surety of purpose that is not unlike that shared by the other defenders as their final days drew to a close. There can be no doubt that his serious illness, which forced him to become bed-ridden mid-way through the siege, made any thought of escape impossible and yet one would have to believe that his defiance of Santa Anna's authority kept him at the Alamo as surely as did his incapacitating affliction.

The Alamo Commander, Colonel William Barret Travis, was born in South Carolina and raised in Alabama. After moving to Texas in 1831 he became caught up in the independence movement and openly spoke of revolution. He lacked any formal military experience but this was off set by his bravery and passionate dedication for Texas independence from Mexico.

Here again, the prospects of wealth (land) and glory in no small measure motivated the 27-year-old firebrand to defy Santa Anna's request for the surrender of the Alamo with a cannon shot on 23 February 1836. Unlike as popularized in all three of the Alamo movies, he would be one of the first to fall while in command of the Texans that defended the Alamo's North Wall.

Lastly, one cannot forget the legendary Davy Crocket, the "High Private" who, along with 14 men of the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers, defended the palisade between the Chapel and the Alamo's Main Gate. The 50-year old "larger then life" frontiersman was a former Congressman from Tennessee and a rugged out doormen who had served with Andrew Jackson's Army during the Creek (Indian) War. Following his defeat for reelection to Congress in 1833, he gained much disfavor from President Andrew Jackson when he argued against the latter's unfair treatment of the Indians.

In the fall of 1835, after a number of successful tours in the East and totally disgruntled with politics, he sought adventure and a new life out West. With a handful of faithful friends, and his trusty fiddle, he bid farewell to his constituents in his typical style...."You may go to Hell and I will go to Texas" and went westward in search of adventure and a new life. For his efforts, he would perish, along with Jim Bowie and Colonel William Travis, on that early Sunday morning at the Alamo.

The Texan Defenders

The Texan Defenders

The men that defended the Alamo were a motley collection of adventurers, foreign immigrants, American volunteers, Indian fighters and opportunist. Excluding the 13 confirmed survivors, it is believed that 189 men died defending the Alamo. Included in this number were 6 Tejanos (Hispanics who were born in what would later become Texas) and one freed Black slave by the name of John. Some also believe that another man, Jesse Bowman, also died at the Alamo but this has never been confirmed.

Of the known 13 survivors, all were woman and children except one. He was Colonel Travis' slave Joe, a Black Man whom the Mexican soldiers did not kill because their government was opposed to slavery. Additionally, many believe that there was yet another survivor, but this too has never been confirmed. His name was Louis "Moses" Rose, who cheated death by fleeing over the wall when Travis offered him an opportunity to escape the night before the final assault.

Of the 189 men who died defending the Alamo 22 were members of The New Orleans Gray's. These militia volunteers were mustered into service at Banks Arcade in New Orleans and arrived in San Antonio in late November 1835. A second company of the "Grays" also served at Goliad, under the overall command of Colonel Fannin. Like he, and some 300 other Texans under his command, they would all be executed, by order of Santa Anna, on 27 March 1836 in what has become known as the Goliad Massacre. It is also believed that 32 men of the Gonzales Volunteers, a unit of mounted settlers from Gonzales, Texas, were also included in the above total.

Of those killed at the Alamo, it is also believed that 30 were volunteers from South Carolina, serving directly under Colonel Travis and 14 were members of the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers, who served directly under Davy Crockett. The remaining 91 were Texas Volunteers who were formed into a single company and were under the direct command of Colonel James Bowie.

Of the types of weapons used by the Alamo defenders, the

New Orleans Gray's carried Model 1816 US Muskets and the

Tennessee Volunteers used Pennsylvania Rifles. Weapons carried

by the other defenders were of a wide variety including British India

Pattern Brown Bess Muskets. These weapons were taken from

General Cos' Mexican troops when they surrendered to the Texans

after the Alamo battle in December 1835. The Texans also used

shotguns. One such weapon, in addition to a sword and flintlock

pistol, is believed to have been carried by Colonel Travis himself.

Of the types of weapons used by the Alamo defenders, the

New Orleans Gray's carried Model 1816 US Muskets and the

Tennessee Volunteers used Pennsylvania Rifles. Weapons carried

by the other defenders were of a wide variety including British India

Pattern Brown Bess Muskets. These weapons were taken from

General Cos' Mexican troops when they surrendered to the Texans

after the Alamo battle in December 1835. The Texans also used

shotguns. One such weapon, in addition to a sword and flintlock

pistol, is believed to have been carried by Colonel Travis himself.

The Texan Artillery

There were between 18 and 20 field artillery pieces at the Alamo plus an 18 pound cannon from the schooner "Columbus". How this large gun found it's way to the Alamo's southwest wall is anyone's guess. Historian's appear to be in agreement that it was brought by the New Orleans Grays, however, this has never been conclusively proven. As for the other "guns", they ranged in size from 3 to 8 inches in bore size of which 2 were placed at the palisades and 3 were mounted on the ramp in the Chapel. The exact placement of the other "pieces" is all speculation.

As to the role they played in the siege they were most effective against the Mexican Infantry during their initial assault at the North Wall. Loaded with canister (shot) these guns wreaked havoc within the tightly packed ranks of the charging Mexican troops until the latter breeched the walls. Had the defenders had sufficient personnel to effectively crew all of their field guns the losses to General Santa Anna's forces would have surely been much higher in number.

Flags of Defiance

Flags of Defiance

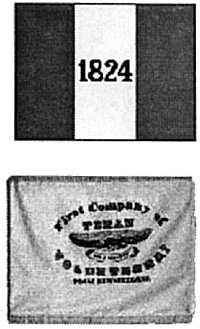

The common consensus is that the "modified" Mexican National flag (1824) was the only flag that flew over the Alamo during the siege. We now know this belief to be incorrect. The "1824" flag is believed to have existed, however, there is no mention that it actually flew over the mission nor is there any surviving reminiscence of this flag in existence today as far as I know.

On the other hand, the flag of the New Orleans Grays is mentioned in "official" Mexican narratives (Lt.Pena) as being the flag that was removed from atop of the Convent after the siege. It still exist today in Mexico City, however, all attempts to have it returned to the United States have failed.

Conclusion

What brought these men to Texas is common knowledge. Vast lands for the taking, adventure and the promise of a new life. Until the last few days of the siege, they held on to the Alamo with a grim hope that Colonel Fannin and his 400+ man army would come to their aid from Goliad.

This didn't happen. They also believed that General Sam Houston would raise an anny and come to their relief post haste. This didn't happen either. When Colonel Travis "drew the line in the sand" with his sword they must have certainly known then that help was not on it's way and that they would die within the walls of the old mission within but a few days. They surely must have known then that any dreams of prosperity, adventure and a new life, the things that brought them to Texas in the first place, would never come to them.

Historians and students of history can debate for centuries as to the reasons, wrong or right, which brought these men to Texas. They cannot debate, however, what motivated them to sacrifice their lives within those crumbling adobe walls in the early morning hours of 6 March 1836. Some could have tried to escape, as did Louis "Moses" Rose. For all we know, some may have succeeded.

But we can be certain that 189 men, of different races, creeds and colors, stood shoulder to shoulder and made General Santa Anna pay dearly for their lives. Mercenaries, opportunist and "foreign interlopers", as Santa Anna called them, do not readily sacrifice their lives in the name of an ideal or common cause. Men of uncommon valor and a tenacious belief in freedom and liberty do.

Despite whatever their individual motives may have been at first, they all chose a common path during the late afternoon hours of the day before their certain deaths. Collectively, almost to the man, they took a big step forward, crossed the line and entered into history. They may have come as freebooters and land grabbers, but they departed as Patriots and Heroes ... Sons of Texas ... one and all.

Credits

The 28mm Miniatures are from the Alamo and Texas War of Independence line by Cannon

Fodder Miniatures.

Santa Anna's Texas Campaign by Stephen L. Harfin

The Alamo ... An Illustrated History by Edwin Hoyt

Fall of the Alamo by Robert Onderdonk

The suburb miniatures shown in this article are 28mm figures from Cannon Fodder Miniatures

The Alamo Part 1 The Mission San Antonio de Valero

The Alamo Part 2 The Mexican Army

The Alamo Part 3 The Texan Defenders

The Alamo Part 4 Days of Glory

The Alamo: A Rebuttal Of Sorts

Back to Dispatch October 2003 Table of Contents

Back to Dispatch List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by HMGS Mid-South

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com