For most of my life I have heard about the famous siege of the Alamo. Most of us have. It was the subject of no less than 3 major motion pictures (another due out in the Fall) and was depicted again in a made for TV mini-series a number of years back. In future articles I hope to go into some depth as to the circumstances that led up to the siege and the information on the actual battle itself. But for openers, a brief background on the Alamo itself may be of interest.

What’s in a Name

Many legend lovers believe that the name “Alamo” came from a near-by row of Alameda (cotton woods) that grew near the mission. Although it is not my intent to dispel this romantic idea, historical documents tell us otherwise. It is now believed that “The Alamo” was an abbreviation for La Segunda Compania Volante de San carolos del pueblo del Alamo, a company of Spanish Colonial Lancers who arrived in Texas in 1803 to strengthened the existing military garrison at San Antonio de Bejar (Bexar). With the occupation of the Mission San Antonio de Valero by the Alamo de Parris Company, there developed a slow name change for the site over the years and by 1807 the buildings themselves were referred to as “El Alamo” (The Alamo) due to the garrison’s presence rather then the cotton woods. While both, the Mission Valero and the Alamo, were both frequently used for the next 20 year, the famous name “The Alamo” eventually dominated due to it’s long association with the military company from Coahuila.

Some of the Company at the Alamo joined the troops leaving from Nacogdoches but most remained at the mission. In 1835, problems arose between the Mexican government of Santa Anna and the Texian settlers. In late September, Captain Francisco Casteñeda, commander of the Alamo Company and some troops were dispatched to retrieve a small cannon loaned to the settlers at Gonzales for defense against raiding Indians. . The citizens of Gonzales refused to surrender the cannon and The Alamo de Parras Company found itself on the receiving end of the first shot of Texas Independence. The Mexican troops that remained behind at the Alamo were reinforced by Mexican Army regulars under the command of General Martin Perfecto de Co’s and together they occupied the Alamo.

Some of the Company at the Alamo joined the troops leaving from Nacogdoches but most remained at the mission. In 1835, problems arose between the Mexican government of Santa Anna and the Texian settlers. In late September, Captain Francisco Casteñeda, commander of the Alamo Company and some troops were dispatched to retrieve a small cannon loaned to the settlers at Gonzales for defense against raiding Indians. . The citizens of Gonzales refused to surrender the cannon and The Alamo de Parras Company found itself on the receiving end of the first shot of Texas Independence. The Mexican troops that remained behind at the Alamo were reinforced by Mexican Army regulars under the command of General Martin Perfecto de Co’s and together they occupied the Alamo.

On 5 December a force of Texians, under the command of Colonel Ben Milam, laid siege to the Alamo, and after 8 days of fighting General Co’s surrendered to the Texians and marched his man force out of the mission and south toward the Rio Grande. The Mission San Antonio de Valero (The Alamo) was now under the control of the Texian “army” and would as such until the early morning hours of 6 March 1836.

The Alamo Compound

Many people assume that the the Chapel was completed and then destroyed during the siege by Santa Anna’s Mexican artillery. Though much damage was sustained, construction on the Chapel would not be completed until after the battle and was never actually used for religious services. However, this being said, the compound itself was still impressive and worthy of focus.

Protective walls enclosed the mission’s main plaza that was rectangular in shape and measured about 160 feet wide (east to west) and 480 feet long (north to south) with Indian dwellings lining the west wall. The main gate (south wall) consisted of an arched entrance and old jail. Colonel Bowie’s sick room is also believed to have been located here and not in the Chapel. Both the south and west walls were constructed of stone, adobe and mud and measured only about 8 feet high. The north wall was about 9 feet high until it reached the northeast corner wherein it was about 12 feet tall. It was constructed of the same materials as the other walls. This section of the compound, which was the defended by Colonel Travis and a portion of the defenders, was the location of the first successful breech of the mission. Remnants of what appears to be have been a ditch were found outside of the south (gate) wall and recovered musket balls from the bottom of this ditch indicates it may have been used as an additional fortification during the 1836 battle.

In an open area between the southwest corner of the Chapel and the southeast corner of the south (gate) wall there is evidence that a palisade had been constructed. Archaeological excavations have indicated that the palisade consisted of two rows of cedar post spaced 6 feet apart and set within a shallow trench. The post were tied together, at the top and bottom, with raw hide strips. In front of the palisade there is believed to have been a long ditch and the excavated soil packed between the two rows of cedar post. The palisade is thought to have been about 3 or 4 feet high and approximately 110 feet long. According to documented information from a few Mexican officers and female survivors, the palisade was defended by Davy Crockett and about 13 members of the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers along with four 4-pound cannons.

Information on the Chapel is far more exact since it, and part of the Convento (east wall-long barracks) remains to this day. The rest of the singles walls and adobes were leveled and the pickets torn up and burned between 22 and 24 May 1836. The defender’s cannons were also spiked or rendered inoperable by the retreating Mexican army.

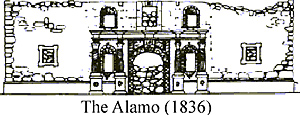

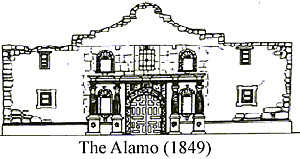

The Chapel was 22 feet-9 inches high during the 1836 battle and prior to the U.S. Army adding the top curvilinear gable between 1849 and 1851. The frontal length of the Chapel is 63 feet-8 feet long and it is about 99 feet deep. The walls of Chapel were 3 feet-6 inches thick, constructed of limestone blocks and roughly finished. There were no doors, windows or roof on the building during the siege so the defenders used chunks of limestone, and whatever else they could find, to barricade the door and window opening.

The Chapel was 22 feet-9 inches high during the 1836 battle and prior to the U.S. Army adding the top curvilinear gable between 1849 and 1851. The frontal length of the Chapel is 63 feet-8 feet long and it is about 99 feet deep. The walls of Chapel were 3 feet-6 inches thick, constructed of limestone blocks and roughly finished. There were no doors, windows or roof on the building during the siege so the defenders used chunks of limestone, and whatever else they could find, to barricade the door and window opening.

A carwalk was constructed so that the defenders could fire their muskets through the upper window openings and the doorway; the above details most often over-looked by Hollywood movie producers and miniature manufacturing companies.

References and Acknowledgments:

The Alamo (An illustrated History) by Edwin P. Hoyt

The Files of Alamo de Parras by Randall Tarin

13 Days of Glory by Lon Tinkle

The Alamo 1836 by Stephen L. Hardin

The Alamo Part 1 The Mission San Antonio de Valero

The Alamo Part 2 The Mexican Army

The Alamo Part 3 The Texan Defenders

The Alamo Part 4 Days of Glory

The Alamo: A Rebuttal Of Sorts

Back to Dispatch August 2003 Table of Contents

Back to Dispatch List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by HMGS Mid-South

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com