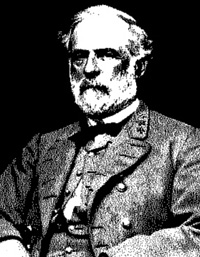

The 1989 edition of the Encyclopedia Americana states that Robert Edward Lee was "one of the truly gifted commanders of all time." This effusive praise reflects the general consensus of opinion on Robert E. Lee. With only occasional dissent, Lee's paramount greatness as a general has been an article of faith, if not dogma.

The 1989 edition of the Encyclopedia Americana states that Robert Edward Lee was "one of the truly gifted commanders of all time." This effusive praise reflects the general consensus of opinion on Robert E. Lee. With only occasional dissent, Lee's paramount greatness as a general has been an article of faith, if not dogma.

The legend of Lee's greatness draws life from his dash, his audacity, his aggressiveness, his tactical genius and his desire to take the offensive. What is rarely, if ever, examined is whether or not he fulfilled his primary role as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia. When that is done, Lee's generalship is found to be lacking, and possibly even counterproductive to the war aims of the Confederacy.

The Why & Wherefore of War

It is important to define what war is. Similarly it is essential to clarify what the Civil War was fought for. War, to paraphrase Clausewitz, is the application of military resources by the State to achieve political objectives. It is violence with a higher intention than mere slaughter. War is the use of the military potential of the nation to gain a political solution which cannot be achieved otherwise. In pure Clausewitzian terms, the American Civil War came about because two political groups, the North and the South, had divergent interests and goals. For reasons not germane to this article, the Southern states concluded they could not accept the constitutional election of Abraham Lincoln. They invoked their perception of the character of the Federal Union and declared themselves in secession. The South's intent was to achieve independence and establish a new nation with a more equitable and charitable climate for their political opinions and goals.

The Union was presented with one of two alternatives when negotiations between the two factions failed. It could either acquiesce in the South's decision or compel the seceding states to remain within the Union. Choosing the latter, the Union's political leadership declared the Confederate states to be in rebellion.

With both sides having rejected acquiescence to the other, and negotiation ruled out by the mutual exclusiveness of their objectives, only one option remained. Force of arms would decide the issue. The South would achieve independence or the North would conquer it.

The Role of a General

The role of a general is to develop and employ the military resources and forces at his disposal for the purpose of providing maximum support for national policy. In a military analysis of Lee, or any commanding general, the critical question is did his conduct of the war help towards achieving the national goal?

Evaluating Lee, or any general, solely on the basis of his dash, tactical skill and aggressiveness, is incorrect. It is analogous to appraising a surgeon's skill at amputation based on his skill at cutting and stitching. A reasonable question would be whether or not the amputation was necessary or improved the patient's chances of survival. That is the central concern in this analysis. Did Lee's generalship and his military policies advance or retard the political objectives of the South? To neglect this central point disembodies and abstracts his battles and campaigns and makes them unrelated to the necessities and objectives of the war they are fought in. Worse, Lee's command is reduced to the level of a theatrical performance.

Lee's task as commander of the Army of the Northern Virginia was not to put on a martial show or a memorable performance. It was to make the maximum contribution toward the South's chances of winning the war -- i.e. achieving its political objectives -- independence.

A word of caution needs to be added at this point. Evaluating Lee in this context and finding him in error, does not mean that if Lee had conducted himself differently the outcome of the war would have been a Confederate victory. Playing "What if" is a futile exercise, and it can not be logically sustained. It is entirely probable that even had Lee been fully effective in the Virginia theater, the Union's military victories in the West and the inexorable advance of those armies to the East might have caused the collapse of the Confederacy anyway.

As discussed above the Union and the Confederacy had divergent war aims. The Union intended to prevent Confederate independence. Militarily this meant that Union had to conquer the Confederacy and destroy its military capacity to resist.

The South's goal was to be released from the Union. The Confederacy's military goals were simply to endure and resist the Union's attempt to impose a military solution. The first question is were those goals reasonably achievable? For the Union the answer is simple --they achieved the political object of the war. For the Confederacy, the question is obscured by a veil of postwar romanticism which must be examined.

The Romance of the Lost Cause

In the immediate aftermath of Appomattox a romantic tradition was born to explain (and justify) the South's defeat. The Confederacy became a Lost Cause -- the impossible dream. It became a war that the South could not have won anyway. The inevitable loss tradition holds that the South was fatally handicapped because of the disproportionate manpower and material resources between the North and the South.

After the war, a Confederate officer summarized the tradition: "They never whipped us, Sir, unless they were four to one. If we had anything like a fair chance, or less disparity of numbers, we should have won our cause." Over a century later, Shelby Foote, restated the inevitability of defeat during the Public Broadcasting System's Civil War Series. "The North fought the war with one arm tied behind its back. If the need had ever arose it merely would have pulled out the other hand and used it."

However alluring and soul-satisfying, the romance of the "Lost Cause" has several fatal flaws and leads to some anomalous conclusions. There is little question that the disparity between both men and materiel was known to both the political and military leadership of the South. Jefferson Davis had been Secretary of War under Pierce and Lee a senior officer in the US Army. The industrial and military capacity of the North vis-a-vis the South was known to both. Subordinates were as well informed.

Adherence to the Lost Cause romance requires believing either that Lee and Davis and their advisors were incapable of assessing the probable impact of this disparity on their war aims -- in which case they were fools. Or that they were aware of it and went ahead with a war which they knew could not win independence for the South.

The latter position requires accepting that Lee & Davis, and the rest of the South's senior leadership, pursued a war with no hope of attaining its political goal. This, in turn, requires believing that the South's leadership deliberately sent its young men off to the slaughter and invited ruinous destruction for no valid reason. In that event the Civil War, was a Southern act of collective suicide.

In that case, the only meaningful analysis of the South's military strategy in the war becomes did the Confederacy wreak more destruction on the North than it had wreaked on them?

If there was no hope for victory than it is proper to judge Lee as little nothing more than the hypothetical surgeon, a performer on a stage. Since there was no hope of victory, questions regarding his generalship become subjective exercises unrelated to war objectives. Did he put up a good fight? Could anyone have done better?

Gratefully, it is not necessary to characterize the Confederacy's political and military leadership as composed of fools or wanton serial killers. There was a reasonable chance for the South to win the Civil War and achieve its independence.

The materiel and manpower disproportion between the two sides was real, but the Lost Cause romance has exaggerated both of these Union advantages beyond their actual scope. In terms of materiel the Union had more resources than the South. But in and of itself this was of little importance. By remarkable and effective efforts the agrarian South was able to create an industrial base that proved adequate, with the aid of foreign imports, to maintain suitably equipped forces in the field. No Confederate Army lost a major engagement because of the lack of arms, munitions or other essential supplies. Shortages in these items became widespread in 1865, but by then the Confederacy was doomed.

The Reality of Union Numerical Superiority

The principal handicap faced by the Confederacy was numerical inferiority though this too is usually overstated. Most engagements between Union and Confederate forces throughout the period 1861-1864 were by equivalently sized armies. Union numerical superiority was also offset by two important factors.

- First, the Union needed to occupy, garrison and defend territory it obtained in its offensives, while guarding its ever lengthening supply lines. This required the detailing of a significant portion of available manpower for the purposes of "defense."

Second, the rifled gun had caused a temporary but significant surge in the power of the tactical defensive. The rifle placed the defender at a significant advantage giving him roughly three times the strength of the offense. The rifle also cost the attacker dearly in terms of relative manpower losses. To attack effectively, as the North would have to do, required a higher ratio of men to the defender.

The Union's manpower advantage while real was not overwhelming in the sense it is usually presented, such as in the earlier quote. The Union's manpower advantage meant that it had the resources to fight an offensive war with a reasonable possibility of victory. It did not guarantee that victory. At the outset of the war, British military experts, drawing on their own experiences in the Revolutionary War, simply did not believe that a country as large as the Confederacy could be conquered. They fully expected the Union would have to give up the effort.

The task facing the Union was an enormous one. Conquest required adopting an offensive grand strategy. Executing this strategy was a gigantic undertaking. The North would have to organize and harness its superior resources in men and materiel then commit them to warfare on a geographic and financial scale that was historically unprecedented. (One frequently overlooked fact is that Washington is farther from New Orleans than Berlin is from Moscow.)

Militarily the North was faced with the task of conquering and then occupying an area as large as the Northern states themselves, (if California & Oregon are excluded.) This area was crossed by rivers and streams, mountains and valleys and wooded, unimproved roads. These natural obstacles impeded any invader who sought to penetrate or hold the area. The Union, committed to an offensive strategy would have to fight on extended lines of communications in hostile country. This in turn required the availability of large numbers of men stationed in the rear to protect these extended lines.

The Union faced an uncertain but real time limit. The Confederacy had to be destroyed before the Northern populace tired of the war and made the political decision that retention of the South was not worth the cost. This was the underlying risk for the Union --that the human, emotional and financial expense of subduing the South would become so burdensome that the Northern people would abandon their support for the war. They could effectively, simply vote a Northern defeat. The risk was genuine --as late as August 1864, Lincoln wrote that he did not expect to be reelected, but instead to be defeated by the Democratic peace candidate -- George B. McLellan.

The South Could Win!

The South was faced with a similar gargantuan organizing job, but inertia was on its side. Its armies could work on interior lines, in friendly country, and with maximum terrain advantages. The North was obliged to come to the South. If the North chose to do nothing, the South would win by default.

There were three ways the Union could have been defeated, each intertwined with the other two. It could have been defeated militarily -- by actual combat in the field. It could have been defeated diplomatically, by European intervention in the war. Finally it could have been defeated politically, by the discouragement of the Northern people.

Much has been written about the risk of British or French recognition of the Confederacy. Such a diplomatic act was always a possibility, at least until the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. What good it would have done the Confederacy is unclear. Recognition would have changed the character of the war in terms of international law and custom. But the assumption that recognition would have led to military involvement by either Britain or France seems to be a will of the wisp. There was no particular reason for Britain or France to antagonize post war relations with the Union by becoming actively involved. Lee himself did not expect European military assistance to the Confederacy and he was a realist on this issue.

The Union could not be defeated militarily. It was simply not possible for the South to conquer the North, nor could the South eliminate the North's armies. However the Union could be defeated politically. Edward Porter Alexander, chief of ordnance for the Army of Northern Virginia, summarized the South's position: "We could not hope to conquer her (the North). Our one chance was to wear her out."

The South could win by convincing the North that coercion could not work and was not worth the effort. To accomplish this the South needed to keep its armies in the field long enough to erode the North's willingness to carry on the war. This is a critical point, the loss of her armies meant the end of the Confederacy.

All things being equal, if Confederate military leadership were adequate, and the Union did not display Napoleonic genius, the tactical and strategic power of the defensive could offset northern numerical advantages long enough for the Confederacy to achieve its war aim of independence.

Evaluating Lee: The Wrong Strategy

Evaluating Lee requires asking the following: What was his grand strategy? What were his perceptions of the dangers to the South's military outcome? Did his actions, within the context of that grand strategy, advance or hinder the war aims of the Confederacy?

Lee rightly understood that a perimeter defense of the South would not work. The Confederacy simply did not have the manpower or materiel resources to conduct a war of position. From the beginning of his command of the Army of Northern Virginia on June 1, 1862 to mid-1864, Lee pursued an offensive grand strategy. He utilized and maneuvered the Army of Northern Virginia in a series of offensive actions designed to achieve a military victory for the Confederacy by destroying the Union army in battle.

In a letter to Jefferson Davis, dated June 25, 1863, Lee stated his rationale for the Gettysburg offensive: "It seems to me that we cannot afford to keep our troops awaiting possible movements of the enemy, but that our true policy is to engage the enemy at points and places of our own choosing." On July 6, 1864, Lee restated his premise that a military solution was appropriate: "If we can defeat or drive the armies of the enemy from the field we shall have peace."

Lee's pursuit of the offensive grand strategy was conducted despite his awareness of the three critical arguments against it:

- a) the disproportion between the South and North in terms of manpower;

b) the consequences to his army of a siege and

c) the need of the South to maintain the existence of her armies.

Lee was also aware that to a large extent Northern popular opinion was the key to the Union's political will to carry on the war. Lee was sensitive to the South's manpower disadvantages and the implications of that disadvantage. During the war, he wrote to Davis that "part of (military) wisdom is to carefully measure and husband our strength." Lee was aware of another problem related to numbers as well -- the consequences to his army of a siege. He consistently expressed the view that his army's being besieged in Richmond was bound to result in its defeat.

There are two possible defenses to a siege. Both require sufficient manpower to either attack the besieging force and drive it away; or to use the forces to protect lines of communication and supply, which in Lee's case meant such avenues as the Weldon & Petersburg Railroad and the Southside Railroad at Petersburg.

Lee hoped to avoid being caught in a siege in the first place. In order for an army to avoid being caught in a siege it must be mobile. And mobility, also requires manpower in reasonable proportion to the opposition.

Lee also recognized the critical need of the South to maintain the existence of her armies. In a letter to Davis on in March 1865 he stated "The greatest calamity that can befall us is the destruction of our armies. If they can be maintained, we may recover from our reverses."

Bleeding the Confederacy White

The losses that Lee suffered that turned the siege into the reality were a consequence of his offensive grand strategy. His grim anticipation of the outcome of his strategy did not, however, moderate that strategy or his commitment to pursuing offensive operations.

Lee's commitment to an offensive grand strategy bled the Army of Northern Virginia white. In his first four months as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee lost nearly 50,000 troops. His losses in Seven Days exceeded the number of effectives in the entire army of the Tennessee the previous autumn. The losses that Lee suffered in his offensives exacerbated another dilemma faced by the Confederacy -- how to deploy its manpower between the its eastern and western armies. In the Gettysburg campaign Lee lost more men than Braxton Bragg had in the Army of Tennessee in August 1862. Lee apologists have attempted to justify this grand strategic blunder by arguing that Lee inflicted more casualties than he suffered. The ten campaigns and battles conducted by the Army of Northern Virginia show that it inflicted 133,330 casualties on the Union while suffering 120,362 of its own -- a net gain of 13,000. If one considers only the losses between Seven Days and the end of Gettysburg campaign, Lee suffered 80,496 casualties as opposed to the North's 72,961 killed and wounded.

Given the South's manpower disadvantages neither of these ratios bode well. The Union was in the unique position of having to defend when it should be in the position of attacking. Lee, in attacking the Union was attriting his own army at a rate the Union could not have expected to achieve on its own.

There was also a profound difference between the casualties the Federal army could afford to take and Lee's. Lee's losses were, by comparison, irreplaceable. The extent of the casualties inherent in Lee's offensive approach risked his capacity to maintain his own army as a viable military force. None of Lee's offensives contributed to the South's political goals. Antietam resulted in Lincoln's decision to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, virtually sealing the end of any possible foreign recognition. Antiwar sentiment in the North did not begin to truly take hold until 1864. Ironically this coincided with Lee's being forced into a defensive grand strategy and the numbing sieges of Petersburg and Atlanta began to wear out Northern enthusiasm for the war. The relative advantage of the tactical defensive is clearly shown in the table.

The only early battle that can be truly considered a Union "tactical attack" is at Fredericksburg. There Burnside, committed to the offensive at all costs, threw his forces at prepared Confederate defenses, and took enormous losses. It was the only battle in which the ANV inflicted twice as many casualties as it suffered. A large portion of these casualties were caused by an ill-advised infantry attack on heights controlled by Confederate artillery. Lee's commitment to the offensive also caused him to make tactical blunders which merely cost lives, and to contemplate actions which would have squandered his men.

At Antietam Lee was opposed to withdrawing and planned to attack the next day, despite his absence of reserves and the presence of an uncommitted Union Corps. At Gettysburg he ordered Pickett's' infamous Charge against the Union's superb defensive position. This latter offense is surprising as the probable outcome of the attack was known to the Union forces who watched it unfold before them. They chanted "Fredericksburg, Fredericksburg," as the Confederates marched into the same error that Burnside had demonstrated on Mary Heights.

Attack & Die!

In Lee's defense, it should be pointed that he was not the only commander in the South committed to the Jomimian-Mahan strategy of the offensive (see S&T 152). In the first twelve major battles of the war, Confederate generals attacked seven times - - at Seven Pines, Seven Days, Perryville, Murfreesboro, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg and Chickamaugua. In those seven battles they inflicted 58,089 casualties while suffering 78,983 of their own. The most amazing apart is that they continued to attack throughout the war as long they as they were able despite the fact that these assaults did nothing but increase the disproportion in manpower between the North and the South.

Lee blundered badly in his selection of the offensive grand strategy. He either lacked a real understanding of the practical circumstances of the antagonists or he was unable to relate a grand strategy to those circumstances. His commitment to an offensive strategy, which he adhered to relentlessly and without reconsideration, accomplished for the Union the effective destruction of his force, prior to Grant's pursuit of a relentless offensive against the Army of Northern Virginia. Fully aware of the consequences of the numeric disproportion between the two armies, Lee made the manpower ratios between the two forces even more favorable to the North, by his insistence on attacking.

Attempts to rationalize Lee's poor strategic thinking by his admirers have at times taken some bizarre turns and they should be addressed. One of the more common myths is that Lee did not intend for his campaigns to result in major battles. This is usually associated with the 1862 Maryland campaign and the Gettysburg campaign. It was not Lee's intent to engage in battle, it was simply a commissary and foraging expedition.

This presupposes that Lee expected the Army of the Potomac to maintain a "wait and see" posture while he entered a loyal state, and moved North of the capital into Pennsylvania. This strains credulity. Lee, in a letter to William Allan, made clear that his intention was to attack McLellan in 1862, and wrote Davis in 1863 that the purpose of the Gettysburg campaign was to give "occupation to the enemy."

Another argument is that Lee had no alternative but to pursue these offensives for reasons unrelated to seeking combat. This is particularly true of the Maryland campaign. The most common justification is that Lee had a need for food supplies and forage, both of which were expected to be readily available north of the Potomac in southern Maryland, while rare in northern Virginia. There are two flaws in this as it relates to the 1862 Maryland campaign. First Lee re-crossed the Potomac on September 18, 1862 and subsisted in Virginia until the Gettysburg campaign, suggesting that both food and forage were available. Second it was not necessary to send an entire army to obtain these commissary supplies if that was Lee's only intent. The Gettysburg campaign was nothing less than an offensive. Lee intended that his army would be pursued and clearly indicated he hoped to meet it in battle and destroy it.

Was There An Alternative?

One last question that needs to be asked is could Lee have conducted his leadership in a different manner? Was there a workable alternative? If an offensive grand strategy was his only option from a military standpoint, than criticism of Lee is incorrect. It has already been shown that a perimeter or war of position was not feasible. There was another choice. Faced with a similar set of circumstances in the War of Independence, George Washington had effectively employed a defensive grand strategy. Washington assessed that, for the colonies to win independence, resistance needed to continue on an organized scale until English public sentiment, lead by Chatham and Burke, would be willing to acknowledge the colonies as an independent nation simply to be quit of the burden of war.

The colonial American army lost many battles and retreated several times. But by keeping his forces in the field, Washington was able to provide a credible resistance to the British, maintain maneuverability and keep the colonial cause alive. The opportunity that presented itself at Yorktown, came about because Washington's overall defensive grand strategy had husbanded his resources for use at a critical juncture for maximum effect.

Lee could have adopted a defensive grand strategy similar to that which Washington used in the Revolution. A defensive grand strategy would have limited Confederate military actions to maintaining resistance to Union advances, maintaining pressure on Union forces in the South and engaging in limited tactical and operational offensives. The underlying advantage to this strategy was that if the Union did nothing in the way of conducting offensives, the South would win by default. If the Union was on the offensives, as it was at Fredericksburg and in the 1864 campaign, the higher casualty rate would have been borne by the Union, not the Confederacy. Lee thus would avoid the costly pattern of offensive war that he pursued in 1862 & 1863.

A defensive grand strategy would not automatically have assured a Confederate victory. However, as the only true disadvantage the South suffered was in comparative manpower resources, it was the only strategy that could minimize the gap between the two adversaries. It was the only grand strategy that made a Confederate victory feasible by husbanding itsmanpower and forcing the north to expend its men.

There is no guarantee that a defensive grand strategy would have worked of course. In terms of negative outcomes it could have involved the loss of Confederate territory, but so did an offensive grand strategy. It could have risked dampening home front morale among a civilian population that craved victorious offensives, but the offensive grand strategy had the same risk.

"The Dictator" a Union mortar used during the siege of Petersburg.

"The Dictator" a Union mortar used during the siege of Petersburg.

Lee's offensive strategy, because of the losses it entailed, led inexorably to the natural military consequences of the enemy's numerical superiority -- surrender. That manpower superiority was enhanced by Federal reinforcements but it was sharpened by Lee's self-inflicted heavy and irreplaceable losses. A defensive grand strategy would have muted the sharpness of the ratios because it would have slowed the increase in the enemy's numerical superiority insofar as the numerical superiority arose from Lee's heavy losses.

When circumstances forced Lee to adopt the defensive grand strategy against his own desires in 1864, that strategy was effective, even though the offensive grand strategy had weakened his army. By combining rapidity of movement with earthworks he blocked Grant at every turn, holding Richmond and Petersburg against Grant's repeated attacks for nine long months. The defensive was skillful, masterful and heroic. The fight Lee put up exceeded in courage and grandeur anything he had yet accomplished during his command. Lee's defensive positions had the effect of sapping northern morale and interest in the war in a way his offensives never did and Lincoln came perilously close to losing the election. Had Lee started the war with a defensive grand strategy it is probable that he would have had available the majority of the 100,000 casualties his offensives had cost the manpower desperate South.

But it was too late.

Summary

An analysis of Robert E. Lee's generalship requires taking into account the elements that make up the Lee tradition -- devotion to the offensive, daring, combativeness, audacity, eagerness to attack, taking the initiative, and a desire to press home battle to the enemy. The wisdom, and hence, the importance, of these qualities is dependent on one's criteria. If one believes that the purpose of a general is to put on a good performance without regard to the outcome of his strategy, then inflicting casualties on the enemy, tactical victories and audacity are enough. A "campaign filled with glorious victories that resulted in total defeat," is adequate, even laudable.

But if the art of generalship consists of using the forces at your disposal, in a way that secures the end for which the war is being waged, and not in a succession of great battles that tend to defeat it, then a very different assessment of Robert E. Lee's generalship is required.

References

Alexander, Edward Porter. Fighting for the Confederacy . Gallagher, GW ed. London: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

Connelly, Thomas. The Marble Man. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977.

Dixon, Alan T. Lee Considered. London: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Encyclopedia Americana, 1989 ed. s.v. "Lee, Robert Edward" Fratt, Steven. Conflict analysis: The American Civil War:

Tactical doctrine. Strategy & Tactics 152:39-44 (June 1992).

Fuller, JFC. Grant and Lee. Reprint. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1958.

Jones Archer. Military means, political ends: strategy. In Boritt, Gabor S. (ed.) Why The Confederacy Lost. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

McPherson, James. Ordeal by Fire. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982.

McWhiney, Grady & Perry D. Jamieson. Attack and Die! Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1982.

Related

-

Robert E. Lee: The Myth and the Mistakes

Robert E. Lee: Comparative American Civil War Casualties Tables

Robert E. Lee Rebuttal: Politically Correct Civil War Interpretations or History?

Robert E. Lee: The Author Replies to Rebuttal

Robert E. Lee: Drawing (CH#7)

Back to Cry Havoc #6 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com