Early that day, Cortes ordered the gold distributed

to packs on the horses, conscientiously saving as much

of the Royal Fifth as possible. Then he called in the notaries

and certified to them no more could be taken, and

told the men to take any of the remaining gold they

wanted for themselves. Some, overcome by greed, took

more of the heavy metal than was prudent. Others,

like, Diaz, grabbed a trinket or two, but balanced the lure

of the treasure against their will to survive.

Early that day, Cortes ordered the gold distributed

to packs on the horses, conscientiously saving as much

of the Royal Fifth as possible. Then he called in the notaries

and certified to them no more could be taken, and

told the men to take any of the remaining gold they

wanted for themselves. Some, overcome by greed, took

more of the heavy metal than was prudent. Others,

like, Diaz, grabbed a trinket or two, but balanced the lure

of the treasure against their will to survive.

Under Cortes' direction, they quickly built a portable bridge to cross the canals (the planned towers had never been completed). Then they waited for midnight. It came, wet and foggy. Visibility was further obscured by a fine drizzle. They made their way to the canal, with the weather serving as a cover and their horses' hooves wrapped in cloth to muffle the sound.

They reached the first canal undetected, set up the bridge and crossed onto the Tlacopan causeway. But an old woman was drawing water and saw the moving troops. She let out a cry. Shouts and whistles answered from the darkness, and thousands of warriors seemed to materialize in seconds. Some attacked from canoes in the canals; others swarmed onto the causeway and mercilessly knifed the booty laden Spaniards.

Cortes, standing amid the chaos on the causeway, called for the rest of the men to hurry and cross the bridge. But he could only watch in anguish as the Aztecs continued to press in on the shrinking detachment on the other side.

The scene was complete carnage. The causeway filled with dead Indians, Spaniards, and horses. Irreplaceable crossbows and muskets fell into the water and were lost along with their owners. The battle quickly degenerated into a contest between Toledo steel and Mexican obsidian, as hand-to-hand fighting ensued all along the column. Some of the Europeans who fell were not killed outright, but were dragged by mobs of Indians toward the temples for sacrifice.

In frustration and rage, Cortes tried to recross the bridge to join the last defenders on the other side. But he was restrained by the men with him until the bridge collapsed under the weight of the men and horses struggling upon it. Those on the other side were thus trapped and lost.

Cortes and his diminished column pressed on until they finally had gained solid ground, where they regrouped at the foot of a large tree. The cost of the breakout had been fearful; Cortes had lost 150 soldiers either killed in action or sacrificed, 2,000 Tlaxcalans, and 45 of the irreplaceable horses. Hundreds more men were missing. Every one of the Spaniards was wounded. Of the 20-odd horses that had survived, not one was fit to run. As he left the city, Cortes, worn by fury, exhaustion and grief, paused for a moment and wept. But the "night of sorrow" was not over yet.

Harried by taunting warriors, Cortes and his men struggled to get out of the city environs. An Aztec army confronted them on an open plain near Otumba. War cries rang out. Guns and powder were long spent; only steel remained. Though suffering from a head wound, Cortes led a charge directly toward the Aztecs' leader (who had made himself conspicuous with an enormous gold banner). After a brief flurry of flashing steel, the cacique was killed, whereupon his warriors fled.

In the unexpected lull Cortes and the tattered rem-nant of the garrison made their way to the stronghold of their Tlaxcalan allies. It was 1 July 1520.

Regrouping

The Spanish spent 22 days healing their wounds and rebuilding their forces at Tlaxcala. The Tlaxcalans, despite the fact Cortes had been defeated and driven from Tenochtitlan, remained fiercely loyal to his cause.

Cortes cast about for more reinforcements and sent a message to the garrison at Vera Cruz asking for men and arms—but not mentioning his expulsion from the Aztec capital. Word of the fiasco must have reached the coast, however, because only seven thin, sickly, and ill-equipped sailors responded to his call. Then some of the men who had come in with Navarez demanded leave to go home. But they withdrew that request when the men of Cortes' original band declared they would stay with him.

Cortes marched to Tepeaca, but found the natives there defiant. Then, in another fit of anger and frustration, Cortes called forth the royal notaries and decreed in their presence that the Aztecs who had revolted were condemned to slavery. This simple but far-reaching act eventually provided the legal basis for the mass enslavement of natives that would occur in the years and decades to come.

The Tepeacans were easily routed in a battle in a cornfield where the Spanish were able to deploy their remaining horses to good effect. Cortes renamed the place Villa Segura de la Frontera, and used' it as a base for raiding the surrounding countryside. The Spanish began freely taking and branding slaves.

Smallpox

Meanwhile in Tenochtitlan, the smallpox epidemic

that had begun shortly after Cortes' arrival claimed the

life of Cuitlahuac, along with thousands of other natives.

Cuauhtemoc, left behind by Cortes, was made emperor

and swore to continue his predecessor's policy of trying

to rid the empire of the Spanish.

Meanwhile in Tenochtitlan, the smallpox epidemic

that had begun shortly after Cortes' arrival claimed the

life of Cuitlahuac, along with thousands of other natives.

Cuauhtemoc, left behind by Cortes, was made emperor

and swore to continue his predecessor's policy of trying

to rid the empire of the Spanish.

Smallpox devastated the Aztecs

Concerned Cortes might attack other provinces, Cuauhtemoc sent troops to reinforce outlying areas. Those troops, however, so mistreated the people of Guacachula and Izucar, two of the main places that had been reinforced, that their populations turned against the Aztecs. They betrayed the Aztec forces' positions to the Spanish and gave over their towns to the foreigners.

Unwittingly, the governors of Cuba and Jamaica also assisted Cortes in rebuilding his forces. Two small ships had arrived at Vera Cruz with supplies for Navarez, sent by the still-unsuspecting Velasquez. The crews of those ships were persuaded to come ashore and carry their cargo up-country to Cortes. Another contingent of 60 men, from earlier expeditions Cortes had sent out, rejoined the main body at Segura de la Frontera. Then two more contingents, which had been dispatched from Jamaica, also arrived. The first group had 53 soldiers and 7 horses; the second had 40 men, all armed with crossbows, and 10 horses.

Smallpox also helped Cortes. As it spread, many leaders among the populace died. Cortes, as a powerful but disinterested party, was asked to settle issues of property and succession. In this way the conquistador was able to select new caciques who favored the Spanish cause, and thus further increased his influence and reputation among the subject peoples of the Aztec Empire.

The Aztecs themselves had fallen into disarray, as Cuauhtemoc struggled against both the epidemic and disruptive forces in his realm.

New troubles arose for the Captain General, though; this time over the ownership of the many new slaves—particularly the female slaves. He had earlier demanded all slaves brought in be turned over to him to be parceled out later. But somehow, when they reappeared, all the good-looking women were gone. The men accused Cortes of keeping too much of a good thing to himself— a charge he vehemently denied. He generously offered to auction off the beauties to the highest bidders—but only after the final battle was won and all the gold of the Aztecs was theirs. No one believed him.

Cortes moved his army back to Tlaxcala and there ordered the construction of 13 sloops, to be used to gain mastery of Lake Texcoco, and to protect his flanks while the main body marched up the causeways to retake Tenochtitlan.

Return to Tenochtitlan

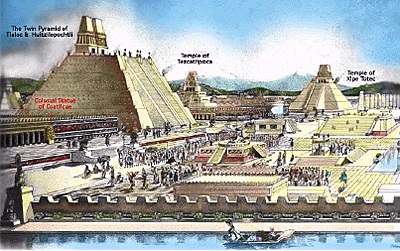

Texcoco was taken in a brief fight in December 1520. Cortes used that place as a base for assembling his squadron of sloops. A force of 8,000 Tlaxcalans transported the components, and another 20,000 warriors joined him as auxiliaries. same day word reached the expedition a merchant ship had arrived at Vera Cruz from Spain laden with powder, arms and other equipment.

This cargo was quickly fetched, giving Cortes the final armament he needed to for the coming battle. From January to May, Cortes slowly invested the great city. He subdued those who stayed loyal to Tenochtitlan, and accepted the allegiance of the others. He cut off the city's water supply through the Chapultepec aqueducts.

The sloops, manned by 300 crossbowmen, musketeers, artillerists (all the cannon were aboard the ships) and oarsmen, held the real key to the war. While Cortes used his other forces to sweep the lake shore and establish garrisons in the towns from which the causeways stretched, his navy fought off all attempts at intervention by the Aztecs. When Cortes finally sent columns marching along the causeways toward the capital, the boats paralleled their course on water, protecting them from assault by the continually probing Aztec canoes. The Aztecs broke the causeways at the city entrances. Cortes brought up his forces. The sloops met swarms of 40-man canoes in continuous combat; their bow cannon wreaked terrible destruction. Cortes eventually penetrated into the city, and his men even reached the market square and briefly stood again atop the pyramid temple. The conquistador expected the Indians to sue for peace, but they continued to resist. Failing to clear the city meant that each night the Spaniards had to fall back to base camps, then renew their probes the next day.

Finally, the senior captains proposed during a counsel of war that Cortes conduct a three-pronged assault into the city, converging on the great market square, where all would reassemble. Once there, they would establish a new fortified camp and remain inside the city. Cortes was doubtful of the plan, but allowed himself to be persuaded.

The three drives immediately encountered heavy resistance, but the Spaniards used their cannon to blast through the defense. Street by street, they pushed forward toward the market square.

Cortes and his column were swept into a trap. The defenders had lain a narrow foot-bridge across a break in the southern causeway. It was so loosely made that in places it sagged into the water. The attacking Spanish swarmed across it, but instead of pausing to properly fill the gap, they pressed ahead into the streets. There they were overwhelmed in a huge counterattack and forced back. The bridge, which had been further weakened by their entrance, could not take the weight of so many in the rush to escape. Spaniards and Tlaxcalans fell into the canal, where they were drowned or killed. Canoes swept in from the lake on both sides.

At the bridge, Cortes tried to check the retreat but had no effect. Heedless of his own safety, he fought wildly. Then he was seized by five Aztec caciques. Rather than kill him immediately, they began dragging him toward the temple altar, where they wanted him to become the greatest sacrifice ever offered to Huitzilopotchli. But a soldier, Cristobal de Olea, sprang to his captain's aid, slaying four of the Aztecs before he was killed himself. Then other Spaniards and Tlaxcalans saw what was happening and rushed in and rescued the conquistador, placing him on a horse and sending him to the rear. That prong of the assault then went back to its base camp, leaving 66 Spaniards captured and a similar number killed outright.

Meanwhile, on the western causeway, Alvarado also met defeat at the hands of the warriors there and was similarly forced to retreat. The Aztecs threw the severed heads of five Spaniards — who Alvarado recognized as member's of Cortes' column—over the wall of his base camp. (Cortes' men were likewise bombarded with the heads of the fallen from Alvarado's column.) The third column also suffered a repulse, but was able to retreat in a more organized fashion.

The three-pronged assault had failed.

Human Sacrifice

The prisoners suffered a fate the rest of the Spaniards could see but were helpless to prevent. Those taken were wrestled to the top of the pyramids and stripped naked. They were then adorned with feather headdresses and compelled to dance in the firelight before the waiting gods. After they had danced enough to satisfy the priests, they were taken, one by one, and thrown on their backs across the narrow stone altar.

The soldiers in the distance watched the priest lift his obsidian knife, curved like an eagle's beak, and saw him open the chest of the prisoner, pull out his beating heart and offer it to the gods. The body was decapitated and kicked down the stairs, where butchers removed the arms and legs for distribution as food to the people, and the torsos were fed to the wild animals kept in cages beneath the temple.

The Aztecs arranged the severed heads of the Spanish victims, as well as those of the fallen horses, in rows on pikes. They adjusted them to face the rising sun.

Cuauhtemoc had the severed hands and feet of the Spaniards sent out to the nearby towns. He declared to their inhabitants that since nearly half the invaders had been killed, it would be best if they broke off their alliances with those who remained. If they did not desert the Spaniards quickly, the emperor warned, the Aztecs would soon return and destroy them.

Final Assaults

The three columns remained in their base camps for

the next five days, repelling repeated attacks. Then the

warriors of Cholula, Huexotzinco, Texcoco, Chalco and

Tlamanalco, who had joined the Spanish in their assault,

suddenly returned home without first consulting Cortes.

Even the stalwart Tlaxcalans departed. The conquistador's

Indian contingent was suddenly reduced from 24,000 to a mere 200.

The three columns remained in their base camps for

the next five days, repelling repeated attacks. Then the

warriors of Cholula, Huexotzinco, Texcoco, Chalco and

Tlamanalco, who had joined the Spanish in their assault,

suddenly returned home without first consulting Cortes.

Even the stalwart Tlaxcalans departed. The conquistador's

Indian contingent was suddenly reduced from 24,000 to a mere 200.

"Why?" asked Cortes of the lone remaining cacique, a Texcocan named Ahuaxpitzactzin. He explained the allies had observed the Aztecs consulting their gods in the night, and that those gods had promised the destruction of the attackers. Looking around at the carnage taking place already, the caciques had become frightened and ordered their troops to leave with them. Ahuaxpitzactzin advised Cortes to avoid any more direct assaults and remain in camp for three days. In the meantime, he advised, the sloops should be used to completely interdict the lake, cutting off all supplies of food and fresh water into the city proper.

While the sloops tightened the blockade of the city, the Spaniards took time to properly fill in the holes in the causeways. When the bridges were repaired and the gaps had been filled in securely enough to allow for safe retreats, they resumed the battle.

The Spaniards advanced each day along the causeways, then retired again to their base camps at night. The Aztecs' attacks on the base camps were equally persistent, but thanks to the sloops and the effectiveness of their cannons, that danger gradually diminished. The fight continued in this way for ten days, with the Spanish slowly advancing into more and more of the city, bridge by bridge, street by street.

The 2,000 Texcocan warriors returned, and were joined shortly by Tlaxcalans, Huexotzingans, and a few Cholulans, again swelling the army to about 15,000.

Cortes addressed them, saying they deserved execution for their earlier desertion, but since they had returned, he would pardon them.

The reinforced army again advanced from all three camps. They found the last Aztec water source, a brackish pool, and destroyed it. They increased the destruction throughout the rest of Tenochtitlan by pulling down every structure they came to.

During this destruction, Cortes sent three captured caciques to Cuauhtemoc with a demand for surrender. Cuauhtemoc discussed the idea with his chieftains, but the Indian priests intervened against it, claiming the gods still promised victory.

Cuauhtemoc then managed to assemble a force from three nearby provinces to fall upon the attackers from the rear. However, after an initial victory, that force stopped to loot, which allowed Cortes to dispatch reinforcements against them. The Aztec allies were defeated and retreated back to their homelands.

With the defeat of the relief force, the fate of the Aztecs was sealed. The slow, inexorable advance of the Spaniards could no longer be stopped. Every house they came to they demolished, and dumped the debris into the canals to fill them. More fires were set and the residents had to flee deeper into the city to take refuge in houses already crowded.

Starvation and thirst also beset the defenders, driving many Aztecs to the Spanish camps, where they surrendered for a meal. At night, Spanish patrols would come upon Aztecs picking among the ruins for herbs and roots to eat, and in the morning would find scraps of gnawed bark scattered about, torn from patio trees. The dead lay so thick in the streets, Cortes wrote, "that the people had nowhere to stand but upon the bodies." Cortes sent a gift of food and a final offer of peace to Cuauhtemoc. Again, though, the Aztec priests counseled for war, claiming a victory was assured.

By now the defense had been compressed into the last one-eighth of the city, an area called Tlateloco. Cortes attacked Tlateloco relentlessly on land, while the sloops bombarded it from the lake. Thus the noose was finally tightened in the denouement of what had become a war of annihilation.

The Spanish pressed their attack. Flames burst from the great temple. A few canoes put out onto the lake in an attempt to escape. But a sloop swept down on them and captured the principal passenger, the Emperor Cuauhtemoc.

Brought before Cortes to surrender, the Indian touched the dagger in the Spaniard's belt. "I have done everything in my power to defend myself and my people and everything that it was my duty to do. Kill me, for that will be best." But Cortes, fearful of committing regicide, kept him alive for four more years, having him executed only after accusing him of taking part in a plot against the Spaniards.

The destruction of the Aztec Empire was complete. It was 13 August 1521, to the Aztecs it was the Day of One Serpent in the Year of Three House.

Epilogue

Death rose from the shattered streets on drafts of sickening air, forcing the conquerors to press cloths against their noses as they passed by. Cortes, sickened by the stench, declared Tenochtitlan uninhabitable, and it was entirely abandoned for six months.

Today in Mexico City, a statue of Cuauhtemoc, dressed in regal robes and headdress and boldly clasping a spear, stands in the middle of one of its largest intersections. It is a fitting memorial to the last, defiant Aztec ruler.

Search as you might, you will find no memorial to Hernando Cortes.

Cortes! The Conquest of the Aztecs by David W. Tschanz.

- Introduction

The Captain General: Cortes

Vera Cruz, Cempoala, Tlaxcala, and Cholula

Tenochtitlan

Breakout, Siege, and Capture

Back to Cry Havoc #38 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com