The settlement at Vera Cruz took several weeks to

complete. Then Cortes decided to march to the large

town of Quiahuitzlan to meet with the cacique there. On

his way his men had to pass through the town of Cempoala.

They sent messengers ahead, announcing their

imminent arrival. Cortes, always cautious, arrayed his

men in battle order as they approached the first large Indian

town they would encounter.

The settlement at Vera Cruz took several weeks to

complete. Then Cortes decided to march to the large

town of Quiahuitzlan to meet with the cacique there. On

his way his men had to pass through the town of Cempoala.

They sent messengers ahead, announcing their

imminent arrival. Cortes, always cautious, arrayed his

men in battle order as they approached the first large Indian

town they would encounter.

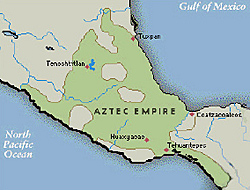

They received a warm welcome. The Cempoalans were recent additions to the Aztec Empire. The leader of the town, so ponderously fat that Diaz never names him, but only refers to him as "the fat cacique," was not pleased with being a vassal of Montezuma. He was emboldened by Cortes' introductory statement that the Spaniards served a different emperor, and he launched into a litany of complaints against the overlords of Tenochtitlan.

Cortes listened and assured the fat cacique he would set things right in the near future. But first, the conquistador continued, he wanted to visit the city of Quiahuitzlan and take up residence there. The fat cacique nodded his agreement and supplied the Spaniard with 400 porters as a token of his good faith. Quiahuitzlan stood amid rocks and cliffs and was a virtually impregnable fortress. But when Cortes approached the place, instead of encountering resistance, he found it abandoned.

Cortes and his men entered, looking for any signs of life. Finally they were met in the market square by 15 leaders and priests who waved incense around the Europeans and bade them welcome. Sheepishly they explained their people had fled at the sight of the horses, and were waiting to see what kind of creatures the newcomers were.

Cortes launched into what was quickly becoming a standard opening speech. He explained the Spaniards were the subjects of the great Emperor Charles; they were worshipers of the one true compassionate God and adherents to the Virgin, and they had come in peace to undo injustices.

As he finished, the fat cacique of Cempoala entered the square borne on a litter and joined the conversations of the Quiahutzilani (who were also of his Totonac tribe). After the fat cacique had explained to them the kind of men the Spaniards were, all the Indians again began complaining to Cortes about their Aztec masters. It was exactly what the Captain General wanted to hear.

A few days later, Aztec tax collectors arrived, putting fear into the Totonacs. They upbraided them for providing the Spaniards sustenance and comfort. In retribution, the Aztec officials ordered them to immediately send 20 additional maidens and young men to Tenochtitlan, as propitiatory offerings to Huitzilopotchli.

When word of this demand reached Cortes, he was enraged. Along the way to Quiahutzilani, and throughout their entire time in Mexico, Cortes and his men had been constantly exposed to the fact the Aztecs practiced human sacrifice on a daily basis (see sidebar). Blood-soaked altars and the remains of human bodies were a common sight throughout the journey, and were a constant source of repulsion and anger to the Christians.

The demand for 20 more victims to be dragged off to certain death in the Aztec capital inflamed their anger anew. Cortes, temporarily masking his feelings, calmly ordered the caciques to arrest the tax collectors (to the amazed horror of all the Indians present), and then sent word to Montezuma about why he had done so. The tax collectors, he said, had exceeded their orders and were robbing the Totonacs, not collecting taxes. This act of bravado and recklessness impressed, as well as frightened, the Totonacs. Cortes, playing a double game, had two of the tax collectors secretly released and sent on to Montezuma as his emissaries.

The Totonacs, in turn frightened by this "escape," were convinced the great Montezuma would send his armies to crush them. Cortes reassured them nothing of the kind was going to happen.

The Aztecs did come, but not the force of warriors the Totonacs feared. Instead, an embassy led by some relatives of Montezuma arrived, demanding to see Cortes--alone. This further impressed the Totonacs about the power and standing the Spaniard had achieved vis-a-vis the Aztecs.

Montezuma's men thanked Cortes for releasing the tax collectors, but then made a bitter attack on his origi-nal action of arresting them. This is not, they pointed out, how a guest behaves toward his host. Cortes si-lenced them. Again he requested a meeting with Montezuma, and the envoys left carrying that request.

Cingapasinga

While waiting for the envoys to return, Cortes heard that Montezuma's tax collectors, backed by an Aztec garrison, were looting the town of Cingapacinga, some 25 miles away. Cortes led his men, reinforced by 2,000 Cempoalan warriors, to right this wrong. When he arrived at the town, the Spaniards found the Aztecs had already moved on. The accompanying Cempoalans then began to loot what remained of the place.

This brought about a predictable response. The Cingapacingan leaders went to Cortes and began to criticize him. They explained the Cempoalans were their ancient enemies, and were now robbing them while enjoying the Spaniard's apparent protection.

Cortes used the opportunity to impress both sides with his sense of justice. The Cempoalans were assembled, and Cortes, with the Cingapacingas looking on, launched into a stream of invective. He accused his allies of being little more than thieves and liars. He scolded them and humiliated them, and warned he would make them sleep in the fields outside the city. He demanded they return all they had looted.

The next day he forced the two tribes to make a pact of friendship, and further insisted they all swear loyalty to the King of Spain. To underscore the seriousness of his words, he had the few Spaniards who had joined in the looting punished as well. It was a performance that showed the natives Cortes meant what he said.

But Cortes was still not done. On their return to Cempoala, he called together the fat cacique and his advisors. After again reaffirming his intent to right wrongs, he proclaimed an end to human sacrifice, the worship of false gods, and the foul practice of sodomy. He ordered they destroy their idols, accept baptism and become Christians.

The Indians were mortified, but Cortes insisted. The confrontation grew intense, but finally the Caciques gave in. In tears they tore down their city's altar to Huitzilopotchli, all the while begging the forgiveness of their gods, telling them they were forced to do it.

The temple area was cleansed of the reddish-black gore from countless human sacrifices. A Christian altar was erected, surmounted by a lofty cross. Cortes had some of the newly unemployed Indian priests of the native gods made acolytes and sacristans in the new church. This was a unique role change for those who only days before had been extracting living hearts from sacrificial victims and offering them to the sun.

Plots Afoot

Having thus Christianized the Cempoalans, Cortes turned his energies to other pressing concerns. How his position and actions were to be presented to the court in Spain was foremost on his mind. Velasquez had supporters there, and Cortes was fearful they would portray him as a traitor to the crown.

He decided to send a single ship to Spain with an account of his actions. To impress the emperor, he also decided to send a gift of all the gold the expedition had acquired to date.

With "honeyed words" he talked the men out of the gold and other gifts they had obtained since their arrival, arguing that the bigger the gift, the more likely it was to impress Charles with their prowess.

The ship was sent with orders to sail directly to Spain, bypassing Cuba. Unknown to Cortes, though, the ship stopped at Cuba because one of its officers wanted to check on his estates there. A sailor left the ship and crossed the island to Santiago, where, deep in his cups, he told everyone in earshot of Mexico's riches.

Word quickly reached Velasquez, who was infuriated at being cut out of what he considered his rightful share of the wealth. He began preparations for a second expedition and sent word to Spain on another ship, denouncing Cortes as a rogue and a thief.

Meanwhile, a plot, probably under the leadership of one of the priests, was hatched by some of Velasquez's partisans among Cortes' men to steal a ship and sail for Cuba. There they would denounce the conquistador and thus ingratiate themselves with the governor.

Cortes discovered the conspiracy and ordered the plotters arrested. Supposedly two of them were executed, and the pilot of the ship had his feet cut off. Only the priest, able to claim "ecclesiastical immunity," escaped punishment.

There is some dispute at to whether the punishments were actually carried out, as one of the men recorded as being executed is also found to have signed his name to a document the following year, and the pilot is known to have gone on to Tenochtitlan with Cortes.

Regardless of whether the sentences were carried out, the idea someone might take a ship for his own purposes began to weigh heavily on Cortes' mind. He therefore had the remaining ships beached, dismantled half, and burned the rest. Arguing it was a safety move because the ships were no longer seaworthy (no one believed him), he then stated there was nothing left to do but advance on Tenochtitlan.

As the crackle of flames swept the beach, the men of the expedition realized they had no way to escape. Resigned, they rallied to Cortes and accepted his notion of conquering the Aztec Empire as their only recourse.

Dreams of gold and glory also drew them. Montezuma's gifts, which had been sent to keep the Spanish away, acted instead like golden lures for Cortes and his men. This lust for gold had earlier drawn Spaniards into and across the Caribbean, and the opportunity to enrich themselves and their king on a scale hitherto unknown was irresistible.

So Cortes organized his men for a march on the Aztec capital. It was, all things considered, a pitifully inadequate force for the conquest of an empire. There were 400 Spaniards, 15 horses, 7 cannon, 1,300 Cempoalan warriors, and another 1,000 porters. From an objective viewpoint, it appeared a gnat was about to go after an elephant.

Tlaxcala

The expedition marched north. The region they passed through would one day be famous for La Vomito and malaria, but at the time was still a pleasant place, since those diseases had not yet been introduced.

Tlaxcala was their first goal. That kingdom was independent of the Aztecs and the sworn enemy of the power of Tenochtitlan. Several Aztec armies had attempted to subjugate the Tlaxcalans, but all had failed, including one led by Montezuma's own son. It was a place to find real allies.

At the Tlaxcalan border, the expedition encountered a stone wall 15 feet high and 20 feet thick, capped by an 18 inch parapet. The entire wall, about four miles long, was anchored in natural buttresses formed by the craggy hills at each end. Only one opening existed in this formidable obstacle. Located in the center, an entrance had been formed by two semicircular walls that overlapped each other for about 100 feet. This "gate" created a 30 foot passage between the two walls that could be commanded from the inner wall, making it easily defensible.

The Tlaxcalan chief, Xicotencatl the Elder, was not pleased with the coming of the Spanish. In addition to the xenophobia brought on by the constant state of warfare with the Aztecs, word had reached him Cortes had received embassies from Montezuma. Still, Xicotencatl feared to attack the strangers outright. He therefore contrived to have his son, Xicotencatl the Younger, a commander in the Tlaxcalan army, advance on the Spaniards without orders from the Tlaxcalan council.

Thus, if the young man were successful, the Tlaxcalans could celebrate a victory. If he failed, the ruling council could disown the attack as the unauthorized act of a mad general.

After crossing the wall unhindered, Cortes and his men were ambushed by a sizable force of Indians. The encounter ended with the Tlaxcalans being driven off, primarily by musketry and crossbow fire.

Envoys from the council came to meet Cortes and explain away the offense. They claimed the road to the seat of government was open and the council members awaited the Spaniards there.

The next day Cortes moved forward again and encountered a larger force of 1,000 warriors. "I come in peace!" the conquistador is reported to have called out. The Indians replied by raining darts, stones and arrows upon the column. Again, the Spanish drove them off, this time pursuing the retreating enemy into a narrow canyon glen cut by a stream. As they turned to leave the glen, they discovered they had been led into a well-contrived ambush. (Cortes, in a later message to Charles V, claimed there were 100,000 warriors waiting, but the number was probably closer to a tenth of that.)

When the Spaniards came fully into sight, the Tlaxcalans let out their war cry, began to beat their drums, and closed in.

The glen worked both for and against the Spaniards. The terrain made it difficult to use the artillery and cavalry to full advantage. At the same time, the Tlaxcalans were unable to bring the full weight of their num-bers against the Europeans. Similarly, the Indians could not effectively flank the invaders because of the protection offered by the canyon walls.

The Spanish closed ranks and engaged in hand-to-hand combat. One Spaniard, named Moran, was pulled off his horse by the Indians, but was immediately rescued. His horse was killed and dragged off by the Tlaxcalans, who later cut up the carcass and distributed the parts throughout Mexico as proof of their prowess.

Cortes

Cortes rallied his men and they were able to force the pass. As soon as they were clear, the conquistadors deployed the artillery and cavalry, which between them were able to drive off the attackers. Accepting this change in the situation, Xicotencatl the Younger withdrew from the field in good order.

Cortes again moved forward, sending embassies to the Tlaxcalan general in an effort to make peace. The reply came back: "Leave or Die."

On 15 September 1519, Cortes' expedition encountered the full Tlaxcalan army, numbering 50,000 men. (Cortes claimed it was about 150,000.) Witnesses stated the Indian array covered a plain six miles square (which supports the smaller figure). They were organized into 10 battalions of about 5,000 each, all under the command of Xicotencatl the Younger.

The Tlaxcalans were armed with slings, bows and arrows, javelins, and darts. Their bowmen were said to be armed in such a way as to make them capable of discharging two or three arrows at a time. In addition, they used javelins with thongs attached, enabling the throwers to recover them for immediate reuse. Their weapons were pointed with bone or obsidian (a hard vitreous rock that takes a razor-sharp edge but is easily blunted), though the spears and arrows sometimes had copper points.

The Tlaxcalans had no swords, but possessed two-handed staffs, about 4 feet long, in which sharp blades of obsidian were. transversely inserted. The chronicler Diaz claimed they could fell a horse with a single blow. Cortes arranged his men to prevent their ranks from being broken by the mass attack he anticipated. But after completing his deployment, rather than awaiting the Tlaxcalan attack, he launched his own.

As the Spanish and their allies charged, the Tlaxcalans, in a scene reminiscent of Crecy, fired a volley of arrows and darts that darkened the sun as it whizzed through the air.

Men fell, but Cortes pressed on, determined to bring his artillery and firearms within range. When those weapons were brought to bear, they cut a swath through the enemy ranks.

The Tlaxcalans charged headlong into the fusillade, and broke the Spaniards' ranks. Cortes was unable to bring his line back into reasonable order, but its individual segments continued fighting with fury. They were helped by the fact the Tlaxcalans were not trying to kill their opponents. Instead, the Indians wanted to capture prisoners for a purpose of which the Spaniards were by now well aware—as victims for sacrifice to the gods.

Another deficiency in Tlaxcalan tactics further aided the Spaniards. While the Tlaxcalan warriors demonstrated a good knowledge of how to launch mass attacks, they were apparently unfamiliar with the principle of concentration on a given point. Diaz credits their salvation to that omission.

The Tlaxcalans, despite vastly outnumbering Cortes' force, were unable to bring more than a small part of their army against the Spanish lines. The end result was their forces in the rear constantly pressed against those in the front, merely contributing to confusion.

The Spanish infantry, though in disarray, were eventually able to reform the semblance of a line and break the Tlaxcalan charges. Cannon then thundered from the flanks and further disrupted the Indian formations. Then Cortes led the cavalry in a charge. He was driven back, but the horses had given the psychological edge back to the Europeans.

The battle degenerated when two Tlaxcalan commanders withdrew their units in the midst of the fight because charges of cowardice had been shouted against them by Xicotencatl the Younger. Their move reduced the army to half its original size.

After four hours, Xicotencatl the Younger called off the attack and withdrew the still sizable remainder of his army from the field. The Spanish and Cempoalans, fatigued by the fighting, did not pursue.

Cortes spent the evening tending his wounded and burying the Spanish dead where they would not be discovered. He did that both to hide the extent of his losses from the Tlaxcalans and to keep them from discovering for certain the Spanish were mere mortals.

Despite his victory, Cortes was not yet out of danger. The Tlaxcalans were not about to give up. At the urging of Xicotencatl the Younger, their caciques asked their priests a question: "Are the Spanish gods?"

"No," answered the priests, "but they are children of the sun. And they derive their strength from its rays. When the sun withdraws his beams, the Spanish will fail."

Xicotencatl argued this meant that while daylight attacks had not succeeded, a night attack would destroy the Spanish.

The night assault was planned and the enemy approached. Cortes had posted extra sentries (whether he was forewarned or just cautious is not known), and they saw the movement of the Tlaxcalans in the full moonlight.

The attack was repulsed.

The Spaniards' detection of their night attack demoralized the Tlaxcalans in a way their defeat in the day battle had not. It appeared to many their gods had abandoned them. How else could the effort have failed? It also increased the superstitious awe of the Spaniards the Indians were developing.

The next day, Cortes again sent embassies to the Tlaxcalan leaders. This time the message was stern rather than diplomatic. The messengers presented the Tlaxcalan council with an arrow and a letter. The meaning was clear—either agree to peace or be destroyed in war.

The caciques chose peace and sent ambassadors to Cortes, informing him their capital was open and he and his men were welcome. Those same ambassadors then went to Xicotencatl the Younger and ordered him to call off the war and supply the Spaniards with food. The young chief disregarded the instructions and imprisoned the messengers. He then sent an embassy of his own to parley with Cortes.

That group immediately became the object of great suspicion on the part of Dona Marina. She noticed its members began drifting away, in twos and threes, after having wandered around the camp and seeing the dispositions of the Spanish and their allies. Warned, Cortes arrested the few still in the camp and accused them of spying. He ordered their hands cut off and sent them back to Xicotencatl that way, with advice not send any more spies.

The discovery of the true nature of his embassy seems to have ended Xicotencatl's desire to resist. He sent another embassy, this time real. The new party arrived at Cortes' camp and offered both peace and food. A few hours later, Xicotencatl arrived with his senior commanders.

At his meeting with Cortes, Xicotencatl was neither compliant nor apologetic. He pointed out he was completely justified in his attacks. Cortes had entered Tlaxcalan lands uninvited, accompanied by the vassals of Montezuma, the Tlaxcalans' sworn enemy. As army commander, he could do no less than what he had done, and he only wished he had been able to do more.

Cortes, impressed by the forthrightness of the Indian, offered a reconciliation. While the rapprochement was accepted, Xicotencatl the Younger remained in the forefront of a minority who wanted to distance the tribe from the Spaniards.

Cortes moved his expedition to the Tlaxcalan capital, where they were feted and proclaimed to be great friends. The two parties soon forged an alliance, and the Tlaxcalans became the Spaniards' strongest allies in the coming campaigns.

One issue, however, that of human sacrifice, almost wrecked the new alliance before it began. Cortes wanted to put an end to the practice in Tlaxcala in the same peremptory way he had in Cempoala—by tearing down the idols and forcibly Christianizing the town. One of the Spanish priests restrained Cortes this time, by arguing their purpose was to expose the natives to Christianity— conversion could be left to those who followed. The priest also pointed out any rash acts might enrage the Tlaxcalans and renew the war. Cortes grudgingly agreed.

The next day an ambassador from Montezuma arrived at Tlaxcala. He stated the Aztec emperor would now be happy to receive the Spaniards at Tenochtitlan, then advised them to move on to Cholula, where a fitting reception was already planned.

Cholula was a city about 20 miles south of Tlaxcala, and 60 miles southeast of Tenochtitlan, lying 6,000 feet above sea level. It was a native religious center, home to a great pyramid dedicated to Huitzilopotchli by the Toltecs. It was the second city of the empire. Montezuma's invitation, which was delivered with much condescension and disdain toward the Tlaxcalan "barbarians," was greeted with suspicion by them. They argued vehemently with Cortes against the move, claiming it was a trap. But their pleas were to no avail; Cortes, ever the explorer-conquistador, had already made up his mind to go to Cholula.

Cholula

Cortes, his party now swollen by an additional 6,000 Tlaxcalan warriors, arrived outside Cholula a few days later. The Cholulan leadership asked him to leave his new allies outside their city, arguing they could provide neither sufficient food or lodging for them. They also pointed out how uneasy they would feel at the presence of so large a force of their traditional enemy in their midst.

Cortes agreed to the request and had the Tlaxcalans quartered in nearby fields. For their part, the Tlaxcalans grumbled and warned Cortes again of the treachery of those who served Montezuma .

At first there seemed little to worry about; the Cholulans treated Cortes and his party well. They were quartered and fed, and shown a high degree of cordiality. But after he had been in the place a few days, more ambassadors arrived from Montezuma. They told the conquistador they had been sent to guide him on to Tenochtitlan.

Upon their arrival, the Cholulans suddenly became distant. They no longer acted open and friendly, and took on an air of unspoken hostility. It was Dona Marina who again brought Cortes confirmation of what he had begun suspecting. She had become friendly with the wife of one of the Cholulan caciques, and that woman had urged the translator to pack her things and come along with the other noblewomen. They were all leaving town, as a plan was afoot. As Dona Marina feigned packing, the chief's wife explained the orders that had just been received from Montezuma: the Spaniards and their allies were to be ambushed as they began to leave Cholula.

Cortes dealt with the news in a subtle way. First he summoned the Cholulan caciques and told them he would leave the next day, asking them to gather the necessary porters. They, of course, immediately agreed. Later the same day, he called in the Aztec ambassadors. Cortes told them he had uncovered a plot by the Cholulans to ambush him. This ambush, the Cholulans had in turn claimed to him, was on the orders of Montezuma. Was that true? The Aztec caciques, caught unaware, denied their emperor's involvement.

Cortes feigned relief and told them he had thought all along Montezuma was blameless. But, he explained, the Cholulans needed to be dealt a harsh lesson because of their duplicity toward him and their slandering of the emperor's honor. Cortes said he would see they were punished for their treason. He then ordered a heavy escort put on the ambassadors, and sent them back to Montezuma, not allowing them to speak to any Cholulans along the way.

The next morning a large number of Cholulan porters gathered in the town's market square along with their principal caciques. Cortes went out to them and denounced them for their treachery. At that, the Spaniards began to massacre the porters and accompanying chiefs. The noise drew the nearby Cholulan warriors who had been waiting in ambush, and soon a full scale battle ensued.

Meanwhile, outside the city, the Tlaxcalans heard the din of combat, so they entered the city and fell upon the Cholulans.

During the battle the Spanish fought their way up the 120 steps of the great pyramid. Upon reaching the temple's summit, they set fire to the wooden structures surrounding the altar.

The fight ended a short time later, with some 3,000-6,000 Cholulans dead. The city belonged to Cortes, and the scene of human sacrifice had been destroyed. Just as the combat was ending, new envoys arrived from Montezuma, denying any imperial role in the plot. Cortes, though he knew the truth of the matter, accepted their word with mock gladness. It became one of his consistent policies to turn a public blind eye to Montezuma's treacheries and to maintain good (surface) relations with the emperor.

At the end of the battle, the Cempoalans with Cortes, who had been growing increasingly uneasy as the expedition drew nearer Tenochtitlan, asked permission to return to their home. They feared they would eventually become the prime target of any retribution by Montezuma. Cortes, who now had confidence in his Tlaxcalan allies, granted their request.

Cortes and his men left Cholula, accompanied by their Tlaxcalan auxiliaries and the Aztec ambassadors. Soon the Tlaxcalans were warning of another possible ambush. Their scouts reported the most direct route to Tenochtitlan had been blocked. The alternate road led through narrow mountain passes, where Montezuma's men might be waiting to fall upon the travelers.

When the column reached the crossroads, they found the direct road to Tenochtitlan obstructed with large stones and tree trunks, just as the Tlaxcalans had warned. Cortes demanded an explanation from the Aztec envoys. They claimed Montezuma had ordered it because it was impractical for horses and cannon to the use that road. The emperor didn't want Cortes to make the mistake of trying to use a route that was impassable to a portion of his force. Cortes replied by asking if the blocked-road was indeed the most direct way to the capital. The envoys admitted it was.

"If it is the most direct route, that it is the one we shall use," the Captain General said, and ordered the obstructions cleared away. This seemed to impress the Tlaxcalans, but aggravated the envoys.

As the march toward Tenochtitlan began, the column ascended the pass lying between the two volcanos guarding the valley. Popocatepetl is a majestic mountain rising 17,852 feet above sea level, making it 2,000 feet higher than any European mountain the Spaniards had ever seen. They climbed into the pass and on reaching its zenith beheld the Valley of Mexico for the first time. It was an amazing sight to them, fertile and verdant. A city on a lake glistened in the distance.

Cortes! The Conquest of the Aztecs by David W. Tschanz.

- Introduction

The Captain General: Cortes

Vera Cruz, Cempoala, Tlaxcala, and Cholula

Tenochtitlan

Breakout, Siege, and Capture

Back to Cry Havoc #38 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com