Tenochtitlan was like no other city they had ever

seen. Built on marshland in the middle of a lake, it was

bigger by far than their own capital of Seville. They

could see the arcaded marketplace. In the center soared

the gleaming lime-washed turrets of the temple complex.

A section of the royal palaces faced it, and beyond that

spread 60,000 flat-roofed adobe dwellings, neatly arranged

along a network of well-kept streets and canals.

Tenochtitlan was like no other city they had ever

seen. Built on marshland in the middle of a lake, it was

bigger by far than their own capital of Seville. They

could see the arcaded marketplace. In the center soared

the gleaming lime-washed turrets of the temple complex.

A section of the royal palaces faced it, and beyond that

spread 60,000 flat-roofed adobe dwellings, neatly arranged

along a network of well-kept streets and canals.

Three long causeways linked the city to the valley floor. Further toward the horizon shimmered a half-dozen other cities.

As they entered the valley, they were met by still more ambassadors. These brought with them rich gifts of gold and Quetzal feathers, and the offer of a bribe to leave. Four loads of gold were promised for Cortes, and one for each of his captains. Montezuma also offered to pay a yearly tribute to Charles V. All he asked the Spanish to do was turn back. Cortes thanked the ambassadors but said he had come to meet Montezuma and pressed on.

At the first causeway they were met by another party of officials sent by Montezuma. This was no ordinary embassy, however, for at its head was Cacama, the ruler of Texcoco and, next to the emperor himself, one of the most powerful men in the realm. Cacama was already angry because Montezuma had rejected his advice to fight, saying that the end of the Aztecs was foreordained.

These newest ambassadors approached, touching the earth with their right hands and then raising them to their heads in the traditional gesture of respect. After another offering of gifts, they escorted Cortes and his party across the lake causeways and into the precincts of the city of Tenochtitlan. It was 8 November 1519.

To enter the city proper they had to cross a wooden drawbridge—a fact that disturbed many in the expedition. The raising of that single drawbridge could cut any escape. This was pointed out to Cortes, but he ignored the warning.

Montezuma and Cortes Meet

They reached a large square. From its other side

came a procession bearing a litter upon which Montezuma

rode in high state. The procession stopped before

Cortes, and the bearers lowered the litter.

They reached a large square. From its other side

came a procession bearing a litter upon which Montezuma

rode in high state. The procession stopped before

Cortes, and the bearers lowered the litter.

Cortes and Montezuma

As Montezuma stepped off, his retainers carpeted the road with their mantles, so the emperor's gem-encrusted sandals never touched the bare earth. Montezuma presented Cortes with the feathered robe of Quetzalcoatl. "We have been the custodians of your kingdom," he said. "We knew you would come some day to reclaim it." Montezuma was about 40 years old at the time. He had an aristocratic and slim figure, straight black hair and a small, thin beard.

It is interesting to speculate what must have gone through the two leaders' minds as they beheld each other for the first time. One was self-confident and felt assured he was destined to be a great conqueror. The other, who had earlier declared himself semi-divine, was not yet certain whether he looked on a returned god or a mere mortal come to despoil.

Cortes, resplendent in the robe that marked him as a god, gave Montezuma a necklace of colored crystal. He then reached out to embrace the emperor, but was quickly restrained by caciques, who—not convinced of the Spaniard's divinity— objected to this bit of lese majesty.

Montezuma had Cortes and his men quartered in the palace of his father. That residence was large enough to provide quarters for all of the 400 Europeans and 7,000 Indians in the expedition.

Capture of Montezuma

A week passed. A cordial relationship developed between Cortes and Montezuma, at times even seeming friendly. Still, anxiety filled Cortes and his men. They were still in alien territory and badly outnumbered. A sudden change in Montezuma's attitude could place them beneath the knife blades of the priests of Huitzilopotchli.

The daily sacrifice of human victims was a strong reminder of the fate that might be awaiting them. Some urged Cortes to take Montezuma hostage, as a way to protect themselves. He agreed, but needed a pretext. That pretext was provided by the death in combat of one of the men Cortes had left behind to garrison Vera Cruz. That fight had been little more than a random skirmish, but when the soldier's head arrived as a trophy for Montezuma, Cortes took the opportunity to accuse the emperor of complicity in yet another plot. The conquistador had the ruler moved from his own palace to the one where the Spaniards were quartered, putting out a story that the move was only temporary, to convince Charles V of Montezuma's innocence.

His position thus more secure, Cortes pressured Montezuma to swear fealty to Charles V, and the Indian agreed. The Aztec summoned his nobles to the palace and reminded them he was their overlord and they had always known they would have to return power to the gods someday. Then he swore loyalty to Charles V, surrendering his possessions and the treasure of his empire to Spain.

Cortes, mindful of the legal formalities, made sure the royal notaries were present and that they properly recorded the pronouncement of Montezuma. Along with their certification, he sent a letter to Charles, stating, with characteristic immodesty, "I have given to you more kingdoms than your father left you towns."

Cortes asked after the source of all the gold he had seen since coming to Mexico. He sent out expeditions, including one led by Francisco Pizarro, to the areas identified by Montezuma, to secure those places and build new towns on them. Then Montezuma turned over the gold in his father's sealed room, the treasure house of Mexico.

Here was what the men had come for, and they were eager to possess it. Cortes began to divide the gold. First he set apart the "Royal Fifth" for the distant Charles, then the fifth due him as Captain General. Another fifth he ordered set aside to pay the cost of the expedition. Then he ordered still more set aside for the chaplain, the crossbow-men, the men who had lost horses, the men in Vera Cruz, etc. In the end, there was so little left to divide among the common soldiers, many refused their small portions in contempt. Complaints against Cortes grew, but he ignored them, promising the men this was only the beginning and what was to come would satisfy their wildest dreams.

Having thus secured gold and glory, Cortes next decided to settle the matters of God. Throughout his captivity, Montezuma had continued to attend the daily human sacrifices and feast on human flesh. His favorite dish, chronicler Diaz states, was "young boy." This appalled the Spaniards.

Cortes told Montezuma the gods of the Aztecs had to change. They were false gods, and must be done away with and the Aztecs all must become Christians. Montezuma refused to even consider such a sweeping idea, but did make some concessions. He told his cooks to stop serving him young boy, and he forced the priests to allow Cortes to place a statue of the Madonna, along with a cross, atop the temple of Huitzilopotchli.

The priests, feeling their power threatened, resisted. Huitzilopotchli, they claimed, was not pleased with sharing his temple. They demanded to leave Tenochtitlan, carrying the image of the god before them, and thus signaling to all the abandonment and displeasure of heaven. While the people had been willing to tolerate the imprisonment of their emperor and the surrender of their national wealth, the departure of their god was unacceptable.

Hostility grew toward the Spanish, and the men in the expedition sensed a change in the atmosphere. The coldness of the people and air of hatred increased. The priests contributed by egging on the people, claiming the gods wanted the invaders dead.

Montezuma warned Cortes the Spanish must leave. Mortal danger faced them otherwise, and the emperor was no longer sure of his ability to contain the explosive situation. This warning came as a confirmation to the growing sense of peril the Spanish already felt, and with it they went, psychologically, from being masters of the empire to men desperately looking for any way out of a deadly trap. Cortes, wanting to salvage what he could, agreed with Montezuma the time had come for his departure. There were, however, two final things the conquistador needed from the emperor. First, Aztec carpenters would be needed at Vera Cruz to help build new ships, since the Spaniards no longer had any that were seaworthy. Montezuma readily agreed and ordered carpenters to assist the Spanish shipwrights.

Second, Cortes demanded Montezuma himself must come to Spain with him, so that Charles V might see him. Again Montezuma agreed, though this time not as happily. It was, he admitted, perhaps the only way to avoid bloodshed.

A decree was put out announcing the gods had ordered the Spaniards be left to depart the city unhindered. For the time being, though the gods might still be appeased with sacrifices, they should no longer be human ones.

While the new ships were being built on the beach at Vera Cruz, the soldiers in Tenochtitlan grew ever more apprehensive. They doubled the guard on Montezuma, who they rightly perceived as their only shield.

Navarez

Delivery from the increasing tension arrived unexpectedly. Word came from the coast that first one ship, then a great fleet, had arrived at Vera Cruz on 23 April. Cortes' initial thought was they must be reinforcements, but he was unsure, and so said nothing to the Aztecs. But the same news had already reached Montezuma, who in turn said nothing about it to Cortes. When the Captain General next visited the emperor, he found the Indian looking cheerful. Cortes inquired into the change of mood, and Montezuma happily displayed the painted cloth pictures of the new fleet that his messengers had brought. His joy, he explained, was that the appearance of this fleet meant Cortes could depart immediately without having to wait to build his own new ships. Cortes examined the pictures but remained noncommittal.

Then Cortes received additional word from Vera Cruz. The fleet, under the command of Panfilo de Navarez, was not one of deliverance, but one sent by Velasquez to arrest Cortes. There were 18 ships, 20 cannon, 2 master gunners, 80 horsemen, 90 crossbowmen, 70 musketeers, and another 1,140 infantry. Their arrival was proof of Velasquez's anger; the expedition's size showed its extent.

Soon after landing, Navarez was greeted by the inevitable emissaries from Montezuma. The Spaniard denounced Cortes as a bandit and entered into secret negotiations with the Aztec emperor.

Three soldiers with Cortes in Tenochtitlan, former followers of Velasquez, abandoned the city and made their way to their old leader, providing him with another account of Cortes' many transgressions. In addition, they described the weakness of the garrison at Vera Cruz and the growing tension in Tenochtitlan between Cortes and the caciques. Buoyed by their report to the point of over-confidence, Navarez ordered a gallows built on a hill near the landing site. From it, he claimed, he would soon hang Cortes.

Navarez then sent a messenger to Vera Cruz warning them of their imminent destruction. This failed to impress the garrison; they took the messengers captive, trussed them up in net hammocks, and sent them on to Cortes.

Leaving behind a force to watch Montezuma, Cortes led 266 men on a rapid march to meet Navarez's expedition while it was still on the coast. Enroute, Cortes sent word ahead offering to negotiate with the newcomer, but his offer was rebuffed. Battle for control of the new territories seemed the only remaining alternative.

Arriving near the site of Navarez's encampment, Cortes organized a night attack against the much larger force. In the darkness and confusion, Cortes' men managed to gain control over the bulk of the camp, but Navarez retreated to a nearby tower. Cortes and his men rushed the tower before a new defense could solidify there. Navarez was wounded in the ensuing hand-to-hand struggle and taken prisoner. With that the resistance ended.

The next morning nearly all of Navarez's men agreed to throw in with Cortes. In fact, they had no real alternative. Besides, Cortes generously offered all of them a share in the treasure of the Aztecs. But before he could take time to savor this increase in his forces, word came of a massacre at Tenochtitlan.

Massacre at Tenochtitlan

The feast of Huitzilopotchli was extremely important

to the Aztecs, and they petitioned Pedro Alvarado,

the officer Cortes had left in charge at Tenochtitlan, for

permission to celebrate it. Alvarado agreed.

The feast of Huitzilopotchli was extremely important

to the Aztecs, and they petitioned Pedro Alvarado,

the officer Cortes had left in charge at Tenochtitlan, for

permission to celebrate it. Alvarado agreed.

That celebration began in the normal manner, and the age-old rituals were followed, except the newly proscribed human sacrifices were omitted. Chanting and dancing began, and song roared through the great square in front of the pyramid. When the ceremonial dance, involving a great throng of priests and warriors, reached a crescendo, Spanish soldiers—perhaps finally frightened beyond endurance by the savage spectacle before them—fell upon the celebrants without warning.

First they attacked the ceremonial drummer, cutting off his hands with a sword stroke. Then they attacked the dancers, slashing and stabbing at will. The Spanish garrison, their fears raised to a frenzy, massacred every Indian within reach.

The stunned Aztecs soon recovered from their own shock and raised the war cry. Slapping their lips with their palms, they shouted aloft their rage and grief and counterattacked. Warriors swarmed from the nearby streets and canals into the plaza. As they poured in, they loosed spears and barbed javelins, tridents and darts, into the ranks of the Spanish.

The Spaniards responded with gunfire and lances, and fought their way back to the fortified palace. Montezuma attempted to call off the Aztecs, but none listened— his credibility with his own people finally had been destroyed. The Aztec warriors called their emperor "a fool." They declared him deposed and elected another ruler, Montezuma's brother, Cuitlahuac.

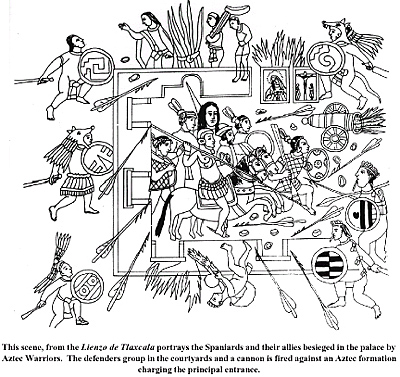

While Cortes rushed back toward Tenochtitlan with 70 horsemen and 500 infantry, the siege of the palace continued. The Spanish garrison attacked anyone who approached. For their part, the Aztecs dredged around the palace island, widening and deepening the channel to prevent the Spaniards' escape. They also built barriers and ramparts in the streets. Human sacrifices began again from atop the great pyramid, in sight of the Spanish, who were shouted to that their turn would come soon.

Besieged

Cortes marched through a suddenly empty countryside. The road and towns along its path were de-serted. The new troops grumbled at the lack of treasure and the scarcity of food. Cortes, trying to calm them, assured them their time at Tenochtitlan would be filled with gold and feathered cloaks.

But Tenochtitlan, too, was ominously quiet. Cortes made a serious mistake by leading his troops through the now-empty streets and into the palace. When Montezuma came out to greet him, the conquistador coldly turned away, angered at the silence of the city. Alvarado gave a series of explanations, perhaps too many, as to what had caused the revolt. The Aztecs had attacked because they wanted to free Montezuma.

The Aztecs had attacked because they believed their gods had ordered them to punish the Spanish for putting up the cross and Madonna. The Aztecs had attacked because the Spanish were still here even though the ships had arrived. The Aztecs had attacked because it would be wise to kill the garrison while the Spanish forces were split. Having been warned, he, Alvarado, had allowed the Aztecs to hold the feast they were going to use as a cover for their attack, and then he had struck them first.

Cortes received his subordinate's explanations with contempt. In a rage he called them "all wrong!" A "great mistake" had been made, and Cortes ruefully said "he wished that Montezuma had escaped."

Two Aztec couriers from Montezuma approached

Cortes and said their master wanted to speak with the

conquistador.

Two Aztec couriers from Montezuma approached

Cortes and said their master wanted to speak with the

conquistador.

The timing was wrong, though, and Cortes snarled at the request: "That dog! He won't hold a market or order food brought to us!" But the Spanish captains tried to appease Cortes' anger, and urged him to make up with the Indian. Calmed, Cortes turned to the couriers again and told them he would be happy to see Montezuma when the emperor thought to order the market reopened and the siege lifted.

The drastic change in the situation was finally brought home when a few moments later a wounded soldier entered the room. He was a scout who had just made his way from a town across the lake to report the Aztecs were massing there in preparation for an all-out attack.

Cortes reacted by ordering a force of 400 men into the square to pacify the Aztecs with a show of force. The detachment had reached as far as the center of the square when they were ambushed by waiting warriors. They had to fight their way back to the palace step by step. Cortes now knew he must contrive some new stratagem for escape, while the Aztecs outside continued to seek a way to finish him off.

The palace in which the Europeans were besieged was made of a vast and irregular pile of stone only one floor in height. In the center, a second partial story had been added, consisting of a suite of royal apartments. A large open area stretched around the building walls, and was in turn encompassed by a stone wall. That outer wall was supported by towers and bulwarks at irregular intervals. The Spanish had placed their cannon on its parapet, and had made apertures for the use of the musketeers.

It was the original Mexican stand off. By day the soldiers sallied out to engage the Aztecs in the network of streets and canals surrounding the palace. But the wooden bridges had been removed, and they could not escape that way.

Nearby houses, from which the Indians had been raining

missiles on the Spaniards, were put to the torch, and the

fortifications in and around the palace were enhanced.

Nearby houses, from which the Indians had been raining

missiles on the Spaniards, were put to the torch, and the

fortifications in and around the palace were enhanced.

At night the city belonged to the Aztecs, who came out to tear down whatever works the soldiers had labored to build that day. The Aztecs also made good use of fire by burning away an entire side of the Spaniards' stronghold. Also at night, from the altar platforms atop the pyramidal temples of the city, there came infernal sounds and taunts accentuated by the glows of the many watch fires. The Aztecs yelled that they would soon stuff themselves on the legs and arms of the Spanish, while their torsos would be fed to the wild beasts and snakes in the pits below.

With the coming of dawn, the Indians would remove the temporary bridges they had put up the previous evening to allow their own movement, and fall back to a safe distance, while masses of warriors kept watch for some opening to reveal itself.

Cortes ordered the construction of three mobile towers with which he planned to bridge the surrounding canals. These wooden structures would each provide cover for 20 men with muskets, and with them in the lead the expedition could, he hoped, force its way across the city.

As the towers were being built, Cortes asked for a truce to allow him and his men to leave Mexico. The request was rejected. Cortes then sent his chaplains to Montezuma, entreating the emperor to ask for a truce.

"What more does he want from me?" Montezuma asked in anguish and anger. Cortes was nothing but "a maker of false promises and a weaver of lies." It made no difference anyway, he told the chaplains; the people had deposed him and elected Cuitlahuac as the new emperor. That cacique, he warned, had sworn no Spaniard would leave Tenochtitlan alive.

The priests begged him to try. Reluctantly, he consented to speak to the people from the roof, though he doubted it would do any good.

Montezuma appeared on the roof of the fortress, surrounded by Spanish soldiers who were ordered to shield him. The nearest Aztecs soon recognized him, and the fighting and commotion in the streets stopped. Three nobles advanced and called up to him. They said they had come to deliver him from captivity. They said the gods had demanded no Spaniard be allowed to leave. The war would end only when the last of Cortes' men had been sacrificed to Huitzilopotchli.

Then stones and javelins flew toward the men on the roof. The guard had relaxed during the Indians' exchange, and they failed to protect Montezuma as they dove for cover. Three stones struck the Aztec, one each on the arm, leg and head. Silently he fell to the ground, his pleas for a truce still unspoken. The guards quickly carried him to his apartments, where it was hoped he would recover. It was 25 June 1520.

The Aztecs outside took up positions atop the pyramid nearest the Spaniards' fortress and began launching missiles upon it in earnest. If left unhindered, they would eventually be able to wreck the palace. Realizing that, Cortes determined to seize the pyramid. The musketeers were sent first, and crawled in broken formation up the steep temple steps, firing volleys into the ranks of the 4,000 Aztecs guarding the place. Behind came the Spanish crossbowmen, swordsmen and dismounted lancers.

The Aztecs struck back from the summit, rolling heavy logs down on the climbing soldiers, crushing some. After being thrown back three times, the Spanish finally fought their way to the top, where they sought the cross and statue of the Virgin. The Aztecs, of course, had removed both. Angered, the Spanish set fire to the tower. With those flames providing a backdrop to his words, Cortes gave a speech, calling upon the Indians to accept the totality of their defeat. Those nearby shouted back their defiance. They were willing, they said, to accept the death of 25,000 Aztecs for every single Spaniard, if that's what it took to rid their land of him and his men.

Shortly after Cortes returned from the sally, Montezuma died without warning. The conquistador allowed the emperor's retainers to carry the body back to his own people. With great sorrow and many tears, they burned the body on a huge pyre.

Cortes sent out word that Cuauhtemoc, Montezuma's cousin and a prisoner of the Spaniards, was now the true emperor of the Aztecs. But the warriors, no longer restrained by the presence of Montezuma, renewed their assaults with increased violence.

Inside the compound, Cortes' men were soon reduced to drinking brackish water, and the battle became continuous. It had been 23 days since the massacre had started the crisis, 7 days since Cortes had returned from the coast, and the situation seemed to be growing more desperate each minute. On 30 June, Cortes resolved to break out or die trying.

Cortes! The Conquest of the Aztecs by David W. Tschanz.

- Introduction

The Captain General: Cortes

Vera Cruz, Cempoala, Tlaxcala, and Cholula

Tenochtitlan

Breakout, Siege, and Capture

Back to Cry Havoc #38 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com