FRENCH STRATEGY

The issue was a tough one: with a new conflict threatening, how could the French defend a huge, open. border against an overwhelming number of Englishmen? Large numbers of French regular soldiers would never be available; the number of French Canadians under army control would, always be limited, and this left the Indians. Now we can see Bougainville's quote from the beginning of the article in-a new light - the Indians were indispensable for French survival. The French were also too weak to defend their territory against a determined English attack, therefore Montcalm's decision, shared by the French government, was to attack and keep the English off balance.

The issue was a tough one: with a new conflict threatening, how could the French defend a huge, open. border against an overwhelming number of Englishmen? Large numbers of French regular soldiers would never be available; the number of French Canadians under army control would, always be limited, and this left the Indians. Now we can see Bougainville's quote from the beginning of the article in-a new light - the Indians were indispensable for French survival. The French were also too weak to defend their territory against a determined English attack, therefore Montcalm's decision, shared by the French government, was to attack and keep the English off balance.

It's interesting to see that almost every major French undertaking that included Indians was successful. French defeats began to multiply as their Indian allies demonstrated less enthusiasm for the cause or simply melted away. Certainly the arrival of large numbers of English regulars often preceded major victories for their side, but this was never a foregone conclusion. The defeat of Braddock's regulars in 1754, the defeat of Maj. Grant in the Forbes expedition of 1758, the clefeat of Montgomery's force in the Carolina expedition of 1760 were all tied directly to successful Indian intervention. French offensive successes at Ft. Bull in 1756, Oswego in 1756 and Ft. William Henry in 1757 were all associated with strong Indian participation.

However while we tend to think of Indians used in large groups to fight regular forces, two Frenchmen made some very clear statements about the best way to make the most use of them. "Their role should be reduced to reconnoitering, or leading the army through woods, rivers and lakes best known to Indians, to fight the Indian auxiliaries of the enemy, to pursue a defeated army, in a word to render services similar to that of cavalry. " (Abbe Picquet quoted in Garand, p. 86). Bougainville voiced similar sentiments. He clearly felt that large bands of Indians were worthless. He also recorded numerous instances where Indians in small parties conducted excellent reconnaissance work and raids (Bougainville, pp. 59-60).

BRITISH STRATEGY

We usually consider the major battles and sieges at Louisburg, Carillon and Quebec as key elements in understanding the French and Indian War. In reality much British strategic, thought involved questions of how to defeat hostile tribes. These few tribes were successful in negating the colonial war effort against the French and forcing the British to bring in large bodies of regulars from overseas. Why werethe colonies largely ineffectual in providing significant numbers of soldiers for the war effort? A few examples should suffice.

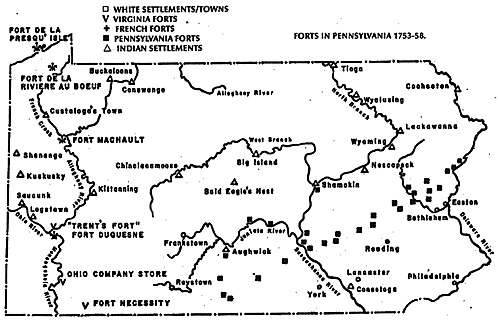

Pennsylvania

From the Battle of the Monongahela in July of 1755 until March of 1756 over 700 people in Pennsylvania, Virginia and North Carolina were killed or captured by the Delawares and Shawnees. In Pennsylvania the reaction was a defensive one; build forts and provide garrisons - over 22 forts plus additional fortified posts and a chain of blockhouses were built across the state. Pennsylvania was not united in a desire to attack the French and their Indian allies. However a compromise was reached where forts were built and garrisoned for a defensive war. Garrisons of 25-75 men were estab Iished for each fort and the Pennsylvania Regiment was formed for garrison work.

Over 1,300 men made up 3 battalions in the regiment and additional groups of 3-20 men garrisoned farmhouses, stockaded mills and smaller blockhouses (Sipe, pp 252-254). With this number of men on defensive duty, it's no wonder that regulars had to be called in for an advance on Fort Duquesne in 1758.

Here we observe a scene which occurred hundreds of times during the French and Indian Wars. A French officer is politely conferring and entreating with an Indian sachem dressed in a captured British greatcoat of the 44th Foot to take part in an expedition already underway versus the British-American colonies. Formalities are being observed and other ranking French officers are also present as is a drummer to lend support-to the importance of the moment. Another pursuasive measure is nearby in the form of a barrel of rum to add stimulation to what is already becoming a rhetorical effusion. The I ndians are thinking pragmatically for themselves wondering what can be gained by assisting the French versus the possible negatives of increasing British power and the reduction of tribal' numbers for a white man's war.

Background miniatures are 25mm RSMs while those in the foreground are 30mm Surens from the collection of Bill Protz. Photo by Bill Kojis. Theme Editor - Bill Protz.

Here we observe a scene which occurred hundreds of times during the French and Indian Wars. A French officer is politely conferring and entreating with an Indian sachem dressed in a captured British greatcoat of the 44th Foot to take part in an expedition already underway versus the British-American colonies. Formalities are being observed and other ranking French officers are also present as is a drummer to lend support-to the importance of the moment. Another pursuasive measure is nearby in the form of a barrel of rum to add stimulation to what is already becoming a rhetorical effusion. The I ndians are thinking pragmatically for themselves wondering what can be gained by assisting the French versus the possible negatives of increasing British power and the reduction of tribal' numbers for a white man's war.

Background miniatures are 25mm RSMs while those in the foreground are 30mm Surens from the collection of Bill Protz. Photo by Bill Kojis. Theme Editor - Bill Protz.

Militia units were established for defensive purposes in 8 counties. Excluding Philadelphia a total of 62 militia units in 7 other counties were enrolled. Twenty-six of these contained rosters of 1789 officers and men on November 4,1756 (Pa. Archives 111, pp. 19-24). All of these men were under local control. In 1757 Pennsylvania had only 1300 men under arms that were available for service outside of their home counties (Pa. Archives, p. 99). Here was a colony. whose resources were spread over numerous counties, not from fear of a French regular army, but in response to numerous Indian raids. On Febraury 5,1758, 2133 officers and men were spread among 32 locations in forts, homes and blockhouses in eastern Pennsylvaina (Pa. Archives III, pp. 339-341).

In 1758 with the Forbes expedition being mounted, Pennsylvania supplied 2700 soldiers for it; the garrisons remained in place, however. Forr Augusta provides one example: if we review returns for portions of the year 1758, we seethe following garrison strengths (Pa.Archives ]V, pp. 341, 374,408, 431, 503, 570):

-

February 5, 1758 362 officers and men

Aprill,1758 361 officers and men

June 2, 1758 124 officers and men

July 1, 1758 198 officers and men

August 1, 1758 175 officers and men

December 1, 1758 175 officers and men

The reduction signals, the beginning of the Forbes campaign, but the number of men still present in the fort stabilizes after July.

Virginia

Through 1756 Virginia established several militia units to defend its frontier. In 1757 the Virginians were able to obtain the services of 400 Indians (Cherokees among them) to protect the frontier (Corkran, p. 115). When

William Crozier lists the Virginia Militia rosters from 1651-1776 based on Hening's Statutes at Large. For September, 1758 and after the departure of once friendly Indians, Virginia listed 1995 officers and men from 10 counties for home defense (pp. 50-108). While the units had obviously been formed before September, complete rosters were given for that month alone. For the Forbes expedition, 2 Virginia regiments participated - five companies of the 1st Virginia and eight of the 2nd totalled some 2600 men at the start of the expedition on July 17 (Bouquet, p. 227). This meant that over 40% of the 4600 officers and men underarms from Virginia never left the state but remained home to defend it; for Virginia, the Indian threat was a severe one.

South Carolina

This colony raised over 1500 men for combat, and all efforts were directed strictly at the Cherokees. Very few men from the Carolinas ever accompanied the major offensives against French territory (Corkran, pp. 191 & 199).

From these three examples we can see that the Indians employed by the French initially threw the English back on the defensive, negated the huge population advantage of the English and finally prolonged the war for several years before the British finally met the challenge.

Massachusetts

When a colony was not directly threatened by Indians, its resources could more easily be applied in concert with other colonial and regular soldiers during the war. While political organization and the will to fight were key ingredients, the lack of a major external threat (Indian raids) should not be dismissed too lightly. Massachusetts for example had paid a heavy price during the earlier Indian wars. In King Philip's War 1675-1676,19 thriving communities had been burnt to the ground or had suffered some serious damage. The colony was hard pressed to defend itself (Leach, Flintlock, p. 243). In King George's War, 1744-48, the Indian threat had diminished and 3000 men sailed off to capture Louisbourg.

During the summer of 1754, Massachusetts sent 800 men north on a fruitless expedition along the Kennebec River. In the winter of 1754, Gov. Shirley received approval to send 2000 men to Acadia to clear out the French and another 1200 men for an expedition to Lake George under William Johnson (Anderson, pp. 9-10). In 1755 Shirley himself helped to

STRATEGIC CONCLUSIONS

While American colonial response to the outbreak of war varied greatly from one colony to the next, one conclusion can be suggested here. Where the colonial frontier was open to Indian attacks such as in New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia or South Carolina, the ability of that colony to respond effectively to the overall effort against the French in Canada was limited. When British regulars made their appearance, they were forced to attack not only Louisbourg and Quebec but undertook two major expeditions against tiny Fort Duquesne, encouraged two large colonial forces to march on Niagara and Ft. Frontenac, and finally launched two more expeditions against Lake George and later Ft. Carillon. They were launched with a view of reducing or ending the greater menace that faced them from French-supported Indians in those areas. Only at Carillon did the British meet a French regular force of any consequence. Otherwise the manpower, the huge expenditures of funds, the long casualty lists and several significant defeats in British colonial territory were tied directly to the war with the Indians.

More Indians from the French and Indian Wars

-

Introduction: Whose Side Were They On Anyway?

French and British Strategy

Tactics

Major Engagements 1754-60

1768 Populations and Sources

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VIII No. 4

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com