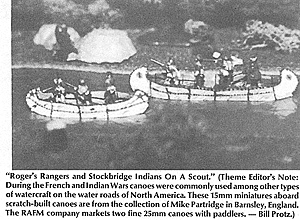

"Roger's Rangers and Stockbridge Indians On A Scout." (Theme Editor's Note: During the French and Indian Wars canoes were commonly used among other types of watercraft on the water roads of North America. These 15mm miniatures aboard scratch-built canoes are from the collection of Mike Partridge in Barnsley, England. The RAFM company markets two fine 25mm canoes with paddlers. - Bill Protz.)

"Roger's Rangers and Stockbridge Indians On A Scout." (Theme Editor's Note: During the French and Indian Wars canoes were commonly used among other types of watercraft on the water roads of North America. These 15mm miniatures aboard scratch-built canoes are from the collection of Mike Partridge in Barnsley, England. The RAFM company markets two fine 25mm canoes with paddlers. - Bill Protz.)

The Iroquois

The Iroquois League was a major political grouping of tribes, mostly living in the area of upstate New York between the Hudson River and the Great Lakes. Their political influence extended over a much larger area, from northeastern Canada south to the Carolinas and west to the Ohio country.

The Iroquois referred to themselves as "Hod eno saunee", or 'People of the Long House'. This had a double meaning, referring to both their traditional living quarters (a wood and bark covered structure roughly shaped like a quonset hut) and the geographic layout from east to west of the tribal territories. There were originally five tribes in the League; their names (in English, French and Iroquois) were: Mohawk/Agnier/ Ganeagaono; Oneida/Onneyut/Onayotekaono; Onandaga/Onnoutague/Onundagaono; Cayuga/Goyogouin/Gweugwehono; and Seneca/ Tsonnontouans/Nundawaono.

The name 'Iroquois' was given these people by the early French. It is said by Parkman that it was derived from the word 'hiro', which means "I have spoken". Apparently members of the Iroquois ended each statement with the word 'hiro', and the French began referring to them by that name.

The Iroquois League's five tribes (or Five Nations) were further subdivided into eight clans - the Wolf, Bear, Beaver, Tortoise, Deer, Snipe, Heron, and Hawk. Members of these clans were intermingled throughout the Five Nations and this served to strengthen ties of loyalty among the tribes. It was also not proper to marry someone from the same clan, and this interweaving of relationships served to futher strengthen ties among nations. Inheritance was strictly matrilineal. As Parkman has put it, "a child may not be the child of his father, but he is most certainly the child of his mother." All property and clan membership was passed down by way of the mother's blood line.

As he has stated, the Iroquois League was a highly developed political organization. Each of the Five Nations had a system of chiefs, ranging from village chiefs up through the principal chiefs of the nation. Each nation further had a principal chief for peace and a principal war chief.

These chiefs were 'elected' primarily through demonstration of their abilities at oratory, logic, argument, prowess in battle and just plain good sense. There was a total of 50 of these principal chiefs, or sachems, with each tribe having a different number. All were considered co-equal, though a special significance was attached to the principal chief of the Onandagas because of his traditional heritage from the founder of the League. Matters affecting all of the Five Nations were decided on by unanimous vote, with each chief having the opportunity to speak on the issue.

When war was the policy, the principal war chief was tasked with formulating a strategy and leading the main war-party. individuals were not prohibited from engaging in their own raids on the local level and this was to cause much misunderstanding between the Indians and the settlers during times of 'peace'. War chiefs were elected on the basis of their prowess in battle, their sagacity and their craftiness in formulating strategy. The style of warfare was at once highly organized and highly individualistic. Elaborate rituals were performed prior to going on the warpath.

Movement to the enemy was as well planned and executed as any Roman legion's. Extensive use of scouts and flank and rear guards was common. Use of fortified camps was also very common when the party was in enemy territory. Battle rehearsals were usually carried out prior to an attack, with each man's place and mission carefully thought out. Once the battle was joined, the individual abilities of the warrior became more important and the war chief's role reverted to monitoring the course of the action and deciding when to sound the retreat. As has been stated, retreat in the face of a superior enemy was not considered shameful; if anything it was considered wise since it preserved warriors to fight another day.

The favored tactic of the Indian warriors was the ambush, since this maximized the enemy casualties and minimized their own. The Iroquois warriors were extremely adept at a variation of this tactic, where a small body of warriors would feign retreat and draw their enemies into a carefully laid killing zone. This ruse worked time and again, even against militia and soldiers who were experienced in Indian fighting.

The Iroquois lived in an area that was relatively poor in fur-bearing animals. The increasing importance of the fur trade, from its sporadic beginnings with French fishermen in the 16th Century, prompted the Iroquois to take aggressive actions to establish themselves as middlemen between the European settlers on the coast and the tribes of the interior. Because of the superiority of metal tools over the flint and stone tools used prior to the advent of the whites, the Indians found themselves increasingly dependent on the Europeans to supply axes, knives, traps, scrapers, combs, kettles, guns, and ammunition. The volume of the fur trade quickly escalated as the Indians found themselves relying more and more upon the modern tools and weapons; indeed, in a relatively short time, the Indians found they had lost the ability to make the former stone tools because the skills required had so rapidly fallen into disuse. Thus, the fur trade became the driving factor behind the Iroquois economy.

Indeed, maintenance of the fur trade became an important factor in the machinations of the French, English and Iroquois in America, causing serious repercussions in London and Paris as well as in the Americas.

It should be noted that the Iroquois were not just fur trappers. They were also accomplished farmers, growing corn, beans, pumpkins, tobacco, sunflowers, and other crops. Irrigation systems and vast orchards of fruit trees are often described in various memoirs. The final breaking of the power of the Iroquois League can almost be said to have resulted not from defeat in battle, but from destruction of their farmlands by General Sullivan's expedition in 1779.

Their villages were fairly permanent affairs, being moved at intervals of 10-30 years as the surrounding soil gave out. Villages consisted of anything from two or three 'longhouses' containing a half-dozen families, up to towns with populations of several hundreds. It was not uncommon for at least one of the houses in the village to be fortified as the strong point in case of attack. Often the entire village would be surrounded by fortifications consisting of a ditch and triple palisade of interlaced logs lined with bark, with timbered galleries from which defenders could shoot or throw stones or other missiles. Though these types of fortifications were proof against anything up to musket fire, the use of cannon by the Europeans spelled the end of this type of construction.

In terms of the various conflicts of the 17th and 18th centuries, the Iroquois sided with whomever they thought would serve their purposes. In general, it can be said that they usually sided with the British against the French, and later with the British against the Americans. Their relations with the various other Indian tribes were based strictly on selfinterest and did not necessarily reflect any "racial" loyalties; indeed, the ultimate failure of Pontiac's uprising after the French and Indian War can in part be attributed to the Iroquois' refusal to become involved. Their neutrality during the course of that conflict allowed the English to concentrate against Pontiac's western tribes; who can say what the outcome might have been had the might of the Iroquois League been added to the fray?

To sum up, the Iroquois League was a collection of tribes, linguistically different from the surrounding Algonquins, who had taken the development of tribal politics as high as it could be. Realizing the value of unity of purpose, they still failed to take the concept to its logical conclusion and broaden their scope to include all Indians. Their political sophistication enabled them to play off the French and English for almost a hundred years, thus enabling them to maintain their independence far longer than most tribes. However, their failure to embrace Pontiac's vision of an Indian Confederation in effect insured their ultimate downfall; by the time Tecumseh arrived on the scene, the Iroquois League no longer had the power to aid anyone.

Individually, the Iroquois warrior was an interesting blend of characteristics; at once brave, pragmatic, amazingly cruel, kind, generous, greedy, and above all independent. He was able to match wits and weapons with the white man for far longer than any other tribe. His ultimate downfall came about not through a lack of bravery or success in battle, but more because of a lack of understanding of the magnitude of the problem facing him.

The Hurons

Linguistically and culturally, the Hurons were of the same stock as the Iroquois; it is ironic that they were deadly enemies. The Hurons lived along the eastern stores of the lake which bears their name today. Their style of living was pretty much as has been described for the Iroquois, though they had nowhere near the level of political sophistication. Farming may have had even more importance, because the hunting was relatively poor in the Huron country. Meat was reserved only for special occasions and corn was the staple.

The Hurons early on realized the importance of the fur trade and they quickly established themselves as the middlemen between the French and tribes further west. This position was just one more point of conflict between the Hurons and the Iroquois, and eventually motivated a war between these two tribes in the mid-17th Century. Unlike previous conflicts that were motivated primarily by revenge, honor or prestige, this was a war of national survival with control of the fur trade as the prize. The Hurons lost and their importance as French allies steadily declined from this point on.

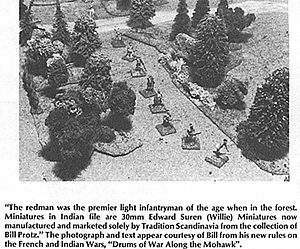

"The redman was the premier light infantryman of the age when in the forest. Miniatures in Indian file are 30mm Edward Soren (Willie) Miniatures now manufactured and marketed solely by Tradition Scandinavia from the collection of Bill Protz." The photograph and text appear courtesy of Bill from his new rules on the French and Indian Wars, "Drums of War Along the Mohawk".

"The redman was the premier light infantryman of the age when in the forest. Miniatures in Indian file are 30mm Edward Soren (Willie) Miniatures now manufactured and marketed solely by Tradition Scandinavia from the collection of Bill Protz." The photograph and text appear courtesy of Bill from his new rules on the French and Indian Wars, "Drums of War Along the Mohawk".

The Shawnee

This tribe has been described as "... the most restless of all Indians" 16 with no little justification. Parts of this tribe lived at various times as far east as Delaware, as far south as Alabama, and as far north as Pennsylvania. They became of importance when they settled in the lands north of the Ohio River in the 1730's. Variously described as an offshoot of the Delaware tribe or descendents of the Hopewell culture in Ohio, the Shawnee were a loose confederation of five clans, or septs; each sept was responsible for some aspect of tribal business.

They were similar to the Iroquois in terms of their means of livelihood, though their politics were not as sophisticated and their method of warfare was not as organized. Village fortification was not practiced and their mode of warfare seemed to be more individualistic. Like the Iroquois, they had a tribal war chief whose responsibilities included formulating tribal strategy and leading the main war party. Individual and small group warfare was also common.

In general, the Shawnee favored the French against both the British and the Iroquois (the Iroquois considered the Shawnee as a subject tribe; this view, however, was not shared by the Shawnee). When the French were later defeated by the English, the Shawnee shifted their allegiance to the British against the Americans.

Because of the intensity of their warfare against encroaching settlers in Kentucky, the Shawnee (a name "... suggestive of aggressiveness, hostility, restlessness and fearlessness..." [17] have been described as "... probably the main force in the Indian coalition that resisted American expansion during and after the Revolution..." [18]

Their savage and unremitting warfare against the settlers in Kentucky very nearly forced the abandonment of the nascent communities such as Boonesborough. The Shawnee have the distinction of having fought in the last battle of the American Revolution. They, along with other Indian allies and British 'advisors', soundly defeated the Kentucky militia at the Battle of Blue Licks. This cycle of warfare, begun at the Battle of Point Pleasant in 1774 (where the Shawnee warriors slugged it out with settler militia in a day-long, stand-up shooting match) would not end for another 20 years until Mad Anthony Wayne defeated them at Fallen Timbers in 1794. The Shawnee flames would again burn bright under Tecumseh, but only for a brief moment.

Other Tribes

There were many other tribes of importance living in what would become Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Michigan. These tribes lived much as has been described and often joined together in fragile (and ultimately futile) alliances to attempt to stop the settlers' expansion into their homelands. These tribes included the Miamis, the Potawatomies, the Wabash, the Weas, the Ottawas and many others. On occasion, tribes from the west (such as the Sioux) or from the south (such as the Creeks) would join in the fight. As has been alluded to, it was the Indians' inability to present a lasting unified opposition to the waves of white settlers that meant an end to the Indians' independence.

The French

Their presence in the New World dates from possibly as early as the late 15th Century. Fishermen from Breton are thought to have been the first to set foot on the shores of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, perhaps as early as 1497, and certainly by 1517. These fishermen would sometimes land and trade with the savage inhabitants of the Atlantic coastline. This trade consisted mainly of furs, which the fishermen found could bring a handsome profit when sold back in the Old World.

From these tentative beginnings grew an increasing interest in the vast area of America. The kings of France, first Charles VIII, then Francis I, then Henry IV, all took a sporadic interest in colonizing this new land across the sea. Exploring expeditions were mounted under such men as Verrazano (in 1524), Jacques Cartier (in 1534) and Champlain (in 1604), all with the object of determining if this new land could somehow be made to turn a profit for the greater glory of France. Attempts at planting colonies were made in 1541 and again in 1542; both failed miserably due to a lack of foresight in the planning and a lack of fortitude in the execution. The most successful of these earliest attempts was made at Nova Scotia, where a colony started in 1604 managed to hang on until 1607. This colony was abandoned because the sponsors failed to turn a profit, and so withdrew (or were unable to continue) their support.

The French were back in 1610 with a new attempt at wresting a living from the New World. This new colony, under Pontuncourt, almost failed as well; however, a new element was added. in 1611, the Jesuits sailed on the ship carrying resupply for the colony, and from that moment on the interest of "people in high places" was assured. There were souls to be saved in the New World, and furs would finance the effort.

From the beginning, the Canadian territories that became New France were handled in a different manner from the English colonies to the south. France treated her new holdings as, in effect, personal holdings of the King. Every facet of life in New France was subject to some regulation of the King. In addition, the Catholic Church (through the Jesuit Order) wielded enormous power in the colony and what was not subject to regulation by the government was very often the subject of some ecclesiastic stricture. Unlike the populous and vigorous colonies to the south, New France was always to remain a dependency of the King.

Instead of opening the doors to wholesale immigration, France limited the numbers of colonists allowed to move to Canada. By 1754, there were not more than 80,000 French inhabitants in a land that stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from Hudson's Bay to the Gulf of Mexico. (By contrast, the English colonies huddled along the Atlantic coast boasted over a million citizens at this same time.) Because of the influence of the Jesuits, strict orthodoxy was the order of the day in determining who was to be allowed in.

For instance, the Huguenots, though loyal Frenchmen, were Protestant, and therefore undesirable in the forests of New France. According to Parkman in Montcalm and Wolfe, the "... clerical monitors of the Crown robbed their country of a trans-Atlantic empire." While he is probably overstating the case just a little, it is undeniable that the emigration policy of France stifled the vigor of her colonies in the New World.

The economy of New France was never more than an appendage of the King's largesse. Much that was routinely produced in the English colonies had to be imported to New France, thereby ensuring its continued dependence on the King. Although artisans were officially encouraged to move to New France, the artificial wage and price controls discouraged them. The fur trade was also subject to this price control and the result was to stifle economic initiative and concentrate power in the hands of a very few men at the top of the colony government.

The governor was like a feudal seignor, ruling over the scattered inhabitants with absolute authority-at least in theory. The governor was charged with representing the King and commanding the troops of the colony. The intendant was responsible for trade, finance, justice and other civil matters. When these two were honest men, the colony prospered. When either or both of these men were less than honest, the colony suffered and peculation ran rampant to the detriment of all.

The advantage that New France had over the fractious colonies to the south was two-fold: the government of New France did not have as a policy the usurpation of the Indians from their ancestral lands; and there was (at least compared to the English colonies) unanimity of purpose in prosecuting any conflicts.

The government of New France did not encourage wholesale exploitation of the indigenous tribes on anywhere near the scale of the English colonies. This may, perhaps, be attributed to the lack of similar population pressures, as well as the influence of the Church. In the eyes of the missionaries, the Indian tribes were just new souls to be saved. With fewer than 100,000 Frenchmen in a land as vast as Canada, there was no reason for conflict over living space as there was in the south. Although the Indian allies of France were used just as much for the Europeans' ends as those of the English, they were, on the whole, treated more fairly and as something close to equals.

The military resources of New France were much more centrally controlled than those in the English colonies. Instead of a loose collection of bickering ministates, Canada was one land, under one government. All males were subject to service in the militia and the colony had its own regular troops (the Troops de la Marine). The King was also willing to send a few battalions of regulars from France to help out in the frequent crises. Though never lavish in such aid, he was more willing in this regard than his English brother. The result of this was that French war plans were always executed with less of the fractiousness that characterized the English campaigns. Though the English were very jealous of their liberties, they paid for it with a horrible degree of military inefficiency. French inefficiency was more due to the criminal cupidity of men in positions of power and trust.

The English and Americans

Much has been written about the English colonies in America, so I will not repeat it here. Suffice it to say that English policy towards the Indians was driven by a strict selfishness that bordered on duplicity more often than not. in spite of the efforts of such sincere and able men as Sir William Johnson to deal honestly with the Indians (and Sir William was known to do a little double-dealing on occasion), most of the British relations with the Indians could be characterized as ,much promised, but little delivered. The Americans were perhaps a little more honest in their dealings, making few bones about their desire to take the Indians' land for their expanding population. Much blood was shed in the effort to push the frontier westwards; by the early 1820's the focus was beginning to shift west of the Mississippi and the character of warfare with the Indians changed forever.

More Woodlands Warfare America East of the Mississipi.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VIII No. 2

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com