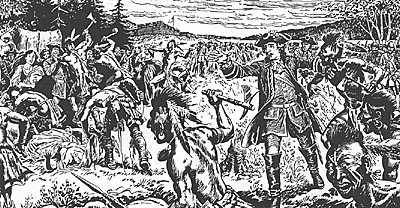

THE MASSACRE OF FORT WILLIAM HENRY - On August 3,1757, the Marquis de Montcalm with an army of 6,000 French regulars and Canadians and 1,700 Indians appeared before Fort William Henry, having come up the lake from Fort Carillon at Ticonderoga. ... Montcalm began a bombardment of Fort William Henry on August 6th. Monro held out against the overwhelming French forces until August 9th, when, despairing of any help from General Webb at nearby Fort Edward, with more than 300 of his men killed and wounded and others sick with smallpox, he agreed to surrender. Upon the terms of capitulation laid down by Montcalm, the English garrison was to be escorted safely to Fort Edward with its baggage and was not to fight again for eighteen months. The garrison, including a number of women and children, moved from Fort William Henry to the entrenched camp. There the English waited through the night, constantly threatened by the savage Indian allies of the French who had already killed a number of wounded men left in the fort. On the morning of the loth of August as the garrison marched out of the camp on the road to Fort Edward, the Indians, thirsting for scalps aud plunder, fell upon the hapless column with their tomahawks. In the bloody massacre that followed, some fifty men, women, and children were killed and 200 were carried off to Montreal as prisoners of the Indians. Many of the survivors fled into the forest. Montcalm and his officers rushed to the scene and, at the risk of their lives, finally brought a halt to the slaughter. Montcalm burned Fort William Henry and on the 16th of August he departed for Ticonderoga without attempting an assault upon Fort Edward. This tragic event typifies the savage nature of Indian warfare in early America. (Theme Editor's Note: We with to thank Frederic Ray who kindly granted permission to use the text and artwork from Lake George: An Exciting History Told In Pictures. - Bill Protz.

THE MASSACRE OF FORT WILLIAM HENRY - On August 3,1757, the Marquis de Montcalm with an army of 6,000 French regulars and Canadians and 1,700 Indians appeared before Fort William Henry, having come up the lake from Fort Carillon at Ticonderoga. ... Montcalm began a bombardment of Fort William Henry on August 6th. Monro held out against the overwhelming French forces until August 9th, when, despairing of any help from General Webb at nearby Fort Edward, with more than 300 of his men killed and wounded and others sick with smallpox, he agreed to surrender. Upon the terms of capitulation laid down by Montcalm, the English garrison was to be escorted safely to Fort Edward with its baggage and was not to fight again for eighteen months. The garrison, including a number of women and children, moved from Fort William Henry to the entrenched camp. There the English waited through the night, constantly threatened by the savage Indian allies of the French who had already killed a number of wounded men left in the fort. On the morning of the loth of August as the garrison marched out of the camp on the road to Fort Edward, the Indians, thirsting for scalps aud plunder, fell upon the hapless column with their tomahawks. In the bloody massacre that followed, some fifty men, women, and children were killed and 200 were carried off to Montreal as prisoners of the Indians. Many of the survivors fled into the forest. Montcalm and his officers rushed to the scene and, at the risk of their lives, finally brought a halt to the slaughter. Montcalm burned Fort William Henry and on the 16th of August he departed for Ticonderoga without attempting an assault upon Fort Edward. This tragic event typifies the savage nature of Indian warfare in early America. (Theme Editor's Note: We with to thank Frederic Ray who kindly granted permission to use the text and artwork from Lake George: An Exciting History Told In Pictures. - Bill Protz.

BACKGROUND

Indian fighting is an activity that is firmly entrenched in the history of the westward expansion of the United States, However, in the popular imagination, an Indian is usually an individual mounted on horseback, bedecked in eagle feathers, and carrying a captured Winchester as he swoops down on a circle of covered wagons. Though this is certainly one aspect of warfare with the Indians, there was another time and place, involving a different type of warrior, that may have been of more importance to the history of the United States.

Warfare involving the Woodland Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi River has a much longer history than the Plains Indian Wars. In a very real sense there was more at stake during the period from the mid-1600's to the early 1800's. This period saw the United States grow from a scattered collection of small colonies to a fledgling world power with the resources of half a continent. One of the first truly "world" wars was started in the Americas during this period. Events of this time led almost inexorably to the American Revolution - who can deny the pivotal nature of that event in world history?

During this period, relations with the various Indian nations were of the utmost importance to the European colonists. Unlike the later Plains Wars, the outcome of which was an historically foregone conclusion, the wars in which the Eastern Indians fought were crucial in determining the size, scope and existence of the colonies and, later, the United States. It was during this period that the Indians had their best chance of stemming the tide of European colonization and maintaining control of both their lands and their destinies. By the end of the War of 1812, the Indians had lost all hope of damming the flood of settlers. Though savage and bloody, the Plains Wars were ultimately the last gasps of a defeated people.

Though of the same basic ethnic stock, the Indians living west and east of the Mississippi had greatly differing lifestyles. These differences were dictated by the types of terrain and the resources available. The vast dry plains of the American West encouraged the adoption of a nomadic lifestyle, heavily dependent on the horse and hunting. Fur trade was important to some of the Plains tribes, but for all of them it was an adjunct to other means of livelihood. The Plains Indian as a general rule fought from horseback, with dismounted action used only for specific purposes. (The Apaches were notable exceptions to this; the mountainous terrain of their home in the Southwest favored foot tactics.) They were motivated to warfare by the need to demonstrate individual prowess, economic factors (obtaining horses, protecting hunting grounds, etc.) and the (vain) hope of keeping the whites out of their lands.

East of the Mississippi the lifestyle was also dictated by the terrain. Generally forested country, numerous streams and rivers, and soils more easily farmed encouraged a more sedentary mode of living. The horse was used as occasional transportation and as a beast of burden; the canoe was a more common mode of travel and fighting was done exclusively on foot. Farming received much greater attention in the East and numerous accounts by early settlers describe vast fields of corn, squash, pumpkins, and other vegetables being tilled by various tribes. Hunting was important, but it did not have the pre-eminent place it held in the West. The fur trade seemed to play a much greater role in the East than in the West. The profits from the fur trade prompted much of the early exploration and settling. [1]

This was especially true in French Canada. The fruits of the fur trade became a two-edged sword for the Indians. Such items as steel hatchets, wool blankets, iron kettles, steel knives, needles, and trade muskets significantly raised the Indians' standard of living. However, the Indians' economies became inextricably linked to the colonists through this fur trade because they were unable to produce these goods for themselves. Competition for trade became stiff among the Indian tribes. A deadly balancing act on the part of the tribes ensued as each tribe tried to preserve their own land, squeeze out the competition and keep the settlers as far east as possible. indeed, as early as 1649, a war was fought between the Hurons and Iroquois primarily over trapping grounds necessary to maintain the fur trade.

Though there were many tribes east of the Mississippi, perhaps none were more preeminent, nor more important in the development of the United States, than the Iroquois. Actually a league composed of several tribes, the Iroquois have been called the "Romans of the West", because of their political organization and geographic location. The tribes lived primarily in upstate New York, though their influence and territory extended as far west as the Ohio country and as far south as the Carolinas. The tribes making up the league were, from east to west, the Mohawk, the Oneida, the Onondaga, the Cayuga, and the Seneca. The Tuscaroras were later taken on as clients of the league, but were never afforded full voting rights.

Never numbering more than a few thousand total population, the Iroquois League wielded influence far out of proportion to its size. "As both France and England knew, their contest for control of the North American continent ultimately would be decided by the choice the Iroquois made between them." [2]

Their geographic location as well as their fighting abilities made them vital to thei interests of any nation seeking to control America north of the Mason-Dixon line. For over a hundred years, the Iroquois' political adroitness and fighting spirit kept them in the thick of the contests between England and France (and later England and the United States). Founded perhaps as early as the 15th Century, the Iroquois League was destroyed after a quarter of a millenium by the upstart Americans.

The mode of warfare for most of the Indian tribes east of the Mississippi was pretty much alike. Most tribes shared the motivational factors of economics, revenge and prestige. Because of the early effects of the fur trade, warfare had pretty much shifted from an individual to a tribal basis by 1700. The various tribes all used similar weapons, consisting of short bows firing flint or steel tipped arrows, flint or steel knives, trade tomahawks, thrusting spears and trade muskets. wooden shields were carried by Algonquin tribes until muskets became common.

The Iroquois also seemed to favor a war club with a heavy, rounded head. The use of fortified villages and camps and hasty field fortifications was also fairly common. Poison, though known by most tribes, was generally shunned. (The Shawnees were known to poison the water supply of an enemy and the Eiries were said to have used poison arrows. The Eries were exterminated in the 1600's by the Iroquois.)

Though generally thought of as highly uncooperative and individualistic, the Indian warriors were considered "the best disciplined troops for a wooden country in the known world". [3]

General orders were well followed and battle drills and rehearsals were very common. However, it must be noted that, after the battle was joined, it was "... carried on in an individualistic manner with little or no control by the chiefs." [4]

Even though he fought for tribal aims, the individual warrior's prowess and display of courage were still the most important.

One aspect of the Indian style of warfare was to prove frustrating to the Europeans trying to fight with them. This was their tendency to break off a battle if they perceived it was going against them. As one author has succinctly put it . they will not stand cutting". [5]

Though often misinterpreted as cowardice or admitting defeat, this tactic was motivated by the Indians' need to preserve their warrior strength. According to another author, their circumstances were such that it was judged necessary for every man to be a soldier. [6]

Low population and birth rates (at least as compare to the Europeans) made it crucial to preserve lives. An Indian war leader who needlessly wasted the lives of his men

would not long remain a leader. Accordingly, the Indians "... rarely

suffered a heavy loss in battle with the whites even when beaten in the

open or repulsed from a fort. They would notstand heavy punishment..." [7];

and they "... usually got off with marvelously little damage." [8]

The Indian leaders would have agreed with General Patton that it was more desirable

to "make the other poor bastard die for his country". it should also be

noted that Indians were quite capable of fighting to the death when left

with no avenue of escape. In such cases they often preferred death in

battle to capture (such an attitude is easy to understand in light of the

frequent fate of many Indian captives). Though adoption into the

capturing tribes or ransom were possible, the fate most dreaded was the

ritual torture of prisoners. Though torture to gain information was

certainly practiced by both sides, there were apparently deeper motives

involved for the tribes. Overtones of revenge, display of individual

courage, group catharsis, appeasement of spirits and protective magic all

seem to be present in the ritual torturing of prisoners. The tribes then

engaged in this practice were not biased in their choice of victims, Indians

as well as white men were all subject to the stake.

The Indian style of fighting was geared to maximizing enemy casualties while at the same time avoiding friendly casualties. The Indian warrior was a supreme light infantryman and a master of guerrilla warfare. According to a more recent authority, their marvelous fighting qualities were shown to best advantage in the woods, and neither in the defense nor in the assault of fortified places." [9]

Ambushes and similar hit-and-run tactics were their strong suits. They tended to avoid pitched battles with equal numbers and sieges were extremely difficult for the warriors' mentality. It must be noted that the penchant for fighting against a foe inferior in numbers was only a general rule; under certain circumstances " - the

Indians do not regard the number of white men, if they can only get them in a huddle,

they will fight them ten to one, and frequently defeat them." [10]

Though the pioneers were acknowledged to be better marksmen, the Indians were

unsurpassed at individual movement and the use of cover and concealment. As an author

has stated, "it is not easy to kill Indians because they are a subtle and artful enemy."

[11]

Another author, in referring to the Shawnee, wrote that "... the superiority of the

backwoodsmen in the use of their rifles... was offset by the agility of the Indians in

the art of hiding and dodging from harm." [12]

The end result of all of these factors was that, though total casualties for both

sides were generally low, the casualties were proportionately much higher for the

whites than for the Indians.

The relatively high casualty rates for the Europeans may be partially explained by

the battle tactics used. An Indian force, as has been stated, emphasized individual

prowess and initiative working within a general, overall plan of attack. The white

soldiers and militia were trained to act as formed bodies, a style of warfare well

suited to the orderly plains of Europe, but deadly in the close forests of eastern

North America. Col.

James Smith, speaking from the perspective of a French and Indian Wars veteran, stated "... British discipline in the woods is the way to have men slaughtered." [13]

Another authority corroborates this assertion by stating "... skilled

backwoodsmen scattered out... but their less skillful or more panic-struck brethren,

and all regulars and militia, kept together from a kind of blind feeling of safety

in companionship, and in consequence their more nimble and ruthless antagonists

destroyed them at their ease." [14]

Even though the individual backwoodsmen generally overmatched their Indian

opponents in both strength and marksmanship, bodies of regulars and frontiersmen

were generally inferior to bodies of Indians. As Col. Smith has said, "it is easier

for a small party to learn to act in concert in scattered order without running into

confusion, than a large army." [15]

The Indians did not have the numbers of warriors to create large armies and so

they maximized their advantage in forest skill.

The character of warfare east of the Mississippi was in sharp contrast to the organized impoundment and extermination carried out in the West. Far more common was the short engagement between a settler and a roving band, the chance encounter of hunting parties, the sudden raid on an outlying community, or the ambush of a flatboat making its way down one of the rivers. Pitched battles between bodies of regulars and large numbers of Indians were not rare (Col. Smith cites 21 'major' campaigns between 1755 and 1794), but far more blood was spilled in these small actions between companies, squads or individuals than ever was in the large campaigns. It was the steady nature of the conflict that accounts for this. Except for a relatively quiet period between the close of Pontiac's uprising in 1765 and Lord Dunmoore's War in 1774, the frontiers were the scene of unremitting low intensity conflict between the encroaching white settlers and the Indians. Periodically the intensity would rise, and often boil over (such as King Phillip's War 1675; King George's War 1744; French and Indian War 1755-1763; Pontiac's War 1763-1765; American Revolution 1775-1783; and so on).

Indeed the period between 1775 and Wayne's expedition in 1794 nearly saw the settlers thrown out of Kentucky, Tennessee and Ohio. Had they been successful, the Indian tribes may have forced the United States to confine itself east of the Appalachians.

By the early 1800's, the end was in sight for the Indians of the East. Tecumseh's confederation was the Indians' last hope to preserve some autonomy east of the Mississippi. Even that hope was a forlorn one; the wave of settlement was pressing too fast and too hard to be held back. Ohio, an Indian wilderness in 1775 with only a few white settlements near the Ohio River, was a full state by 1803. Kentucky, the "dark and bloody ground", had grown from a small collection of precariously held settlements in 1775 to a full state by 1792. The battle of Tippecanoe in 1811 was the end of settlement threatening Indian warfare east of the Mississippi.

Though flare-ups would continue (the Creek War 1813-1814; the First Seminole War 1817; Black Hawk's War 1832; Second Seminole War 1832-1841), the focus of major warfare had shifted west with the inexorable advance of the settlers. Though blood would continue to spill, the Indians would never again have the chance to stem the tide.

The character of warfare had changed with the locale. Cavalry, regular troops, a system of forts, and organized wagon trains took the place of the lone pioneer family pressing just a little farther into the forest. it must be remembered, when speaking of the early pioneers, that "... the land was really conquered not so much by the actual shock of battle between bodies of soldiers as by... the unceasing individual warfare waged between them and their red foes." [16]

This individuality and spirit of selfreliance has been indelibly stamped into everything American from that day to this.

More Woodlands Warfare America East of the Mississipi.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VIII No. 2

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com