(reprinted from Savage and Soldier, Vol XI No. 2, Apr-Jun 1979)

In military terms a frontier is either a barrier or a bufferzone. It limits the scope of military activity and defines the limits of strength. A defender can expect reinforcements while a raider cannot. A miscarried raid can leave the initiator exposed to retaliation, but the effect of a successful raid on theenemy's military capabilities could well outweigh the risks of failure. The position of the frontier in the colonial period, in the lulls between campaignsof conquest or retaliation, was a very delicate one. The consequences of an incursion were often calculated in political, rather than solely military terms.

Most wargames set up on a frontier are usually concerned with location the venue of a battle for aesthetic or historical reasons. Few of us use a frontier scenario to confine our battles within certain limits, nor do we see the outcome as being anything other than purely military. In a series of unconnected wargames that are not part of a campaign, it is difficult to see how it could be otherwise. But it might be possible, by imposing a type of points system on different set-ups, to provide wargames whose outcomes may be quite startling, though consistent with historical precedent. First we must identify what types of frontier battles there may be.

We need not concern ourselves with those frontier battles that are limited by the strategy of a campaign - battles to establish, shift or maintain a frontier line. These battles are very much like conventional wargames in that they don't necessarily lead to another. What does concern us are those battles which must be fought within the limits the frontier provides. Such battles or skirmishes include raids of annoyance, breakthroughs and skirmishes of political consequences.

Raids of Annoyance

When a frontier exists between two well-defined territories (i.e.; India and Afghanistan, Egypt and the Mahdist State, the Mahdist State and Abyssinia) the most common sort of frontier skirmish is the raid. Here a small band must cross the frontier, accomplish some specific objective, and recross the frontier avoiding the enemy forces entirely, or retiring with a minimum of casualties.

The advantages to the raiding force are surprise and mobility. Those of the defenders are prepared defenses and the possibility of bringing up reinforcements. The objectives of the raiders could be supplies (herds of camels, horses, cattle, etc.), damage (burning cultivation and enemy controlled villages), ambush of enemy patrols, or propaganda (leaving some marker behind, such as a flag with printed slogans, or just to emphasize to the surrounding populace the ability to penetrate the frontier).

Both Imperial and native armies could attempt any of these four types of raids, but foraging and ambush are probably best done by native troops. If Imperial troops were given the advantages of mobility and surprise in addition to firepower, they would be difficult to defeat.

In setting up either of the first two types of raids, the objectives of the raider (herds, cultivation, houses) should be assigned certain points values and be scattered throughout the center of the board. The raider would have to try to accumulate as many points as possible before moving off the board, back to his baseline. As mobility is the key to his success, his force should be either entirely mounted on horses or camels, or have a supporting group of footmen who would be restricted to a certain range of action near the baseline. In this way they could offer support to a retiring force, but they could not actively engage in seizing many of the objectives.

The defending force should have only a portion of its troops on the board. Starting at their baseline, they would send out patrols. Only when they have discovered enemy activity can they bring up reinforcements, and some time limit must be imposed on their ability to inform and bring up these reinforcements. Another way is for the herds or villages to be protected by a small squad of gendarmerie of "friendlies" who must send a messenger across their own baseline before reinforcements were brought up, again after a fixed lapse of time.

The game ends when the raider recrosses the frontier by recrossing his own baseline. The outcome of the game is determined by points: each side adds the value of the objectives they have either gained or retained to the points of those troops still intact at the end of the game. The one with the most points wins. Troops that have been forced off the board by morale during the battle are either not counted at full value, or not counted at all. This way the raider must lose something for troops that have been forced to retreat prematurely.

The last two types of raids are best set up as patrols which are either ambushed or must contact the enemy while it is in pursuit of its propaganda aims. Again the defender may not have all his troops on the board and may bring up reinforcements only after they have been notified. The raider may try to break off hostilities and recross his baseline before the reinforcements come into play, but the game will again have to be decided on the points of the remaining forces intact, whether they are fully deployed on the board or not.

That way a raider may not win by deploying all of his forces on the board, inflicting a few casualties on the ambushed patrol, and recrossing the baseline before reinforcements can come onto be counted. In patrols of propaganda, certain points are added for planting markers or leaflets (a fixed numberisgiven before the game) beyond a certain distance from the baseline. In some games these points may be eradicated if the defending patrol is able to locate and remove the markers before the raider has left the board.

Breakthroughs

This may sound like trench warfare, but in some of the earlier colonial campaigns the establishment of an imperial frontier did not always mark the extent of full imperial dominion. Rather, it marked the limit of possible activity.

This was especially the case in Uganda in the 1890's when the Uganda Rifles and their Baganda allies managed to push Dabarega of Bunyoro across the Albert Nile. The Nile then became the frontier, and the frontier was maintained by a series of forts and outposts of Sudanese soldiers. But the territory behind the forts was by no means conquered, and the outposts were maintained mostly to prevent Kabarega from re-entering the country and raising his forces within the territory claimed, but not fully administered, by the protectorate government.

A similar fear was felt on the Congo border when mutinous Congolese askaris tried to enter Uganda, and in the 1897 Sudanese mutiny, much of the government's military activity was taken up trying to prevent different groups from meeting and combining.

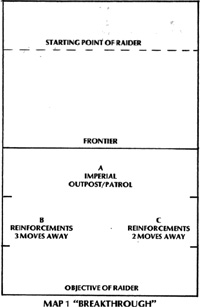

In the breakthrough, some Imperial troops must be on the board in the form of an outpost or patrol. The "raider" must get off the board, but this time he must get off the opposite end from where he started. The Imperial troops on the board can send for reinforcements, but they should not be from the baseline the "raider" is trying to cross.

The frontier in this type of battle runs straight across the

middle of the board; thus any reinforcing patrols or outposts

must be in line with the original placement of Imperial troops.

Their distance from the board, as well as' their entrance

points should be known in advance (see Map 1).

The frontier in this type of battle runs straight across the

middle of the board; thus any reinforcing patrols or outposts

must be in line with the original placement of Imperial troops.

Their distance from the board, as well as' their entrance

points should be known in advance (see Map 1).

A certain time must be allowed for a messenger, once he leaves the board, to reach them, and another period of time for them to get on the board.

Obviously, if the force attempting the breakthrough can prevent or delay the sending of the message, or reach the entrance points to oppose the reinforcements' entry, the better are the chances of making a breakthrough (different rules must, of course, apply if heliographs or other long-range methods of communications are used). The time needed for reinforcements to come being known, the raider may try to get off the board before they arrive. It may also be a good idea to have two groups of potential reinforcements located on different sides of the board, but each being different distances so that their arrival would be staggered.

In this sort of battle the outcome of the game is determined solely by the success and size of the breakthrough. If none get off, the raiders lose. If a leader (either national or of a mutiny) is trying to cross the frontier, then the emphasis must be upon his success, rather than the success of the entire force. His points value once off the board should be nearly equal to the set-up points of the rest of his force, enabling him to cross the opposite baseline with a small force comprising a simple majority of the original value of his entire force (including himself). In some games it might even be preferable to count raiding troops left on the battlefield as only half casualties. They can be used to "soak- off" opposing troops to allow the leader a chance to get across.

Once he does they may disengage and try to get off the board at their original baseline, and only half their points value would be subtracted from the leader's force. Needless to say, if a leader is not involved, and a body of troops is trying to cross the frontier to link-up with another body of troops, a simple majority must cross the opposite baseline. Any that are prevented from doing so are counted as full casualties. When a link-up is attempted, the raiders might be given the chance to bring up some reinforcements of their own, entering from the baseline they are trying to cross, but subject to all limitations of other reinforcements.

Like foot soldiers in raids, their radius of activity on the board must be limited. Any casualties they sustain must be counted, either at full or half-value and subtracted from the total of the force that does breakthrough, for though they are not part of the original breakthrough, their loss materially weakens the link-up.

Skirmishes of Political Consequence This is a rather round-about way of saying that the final outcome of a wargame will not depend solely on the battlefield, but how the skirmish itself isjudged to affect the political balance of a frontier. If a raider's camp is just across the border, does an Imperial patrol risk crossing it to destroy the camp? Will failure to completely or severely damage the raider's headquarters enhance his prestige and increase his following?

In the early campaigns against Muhammad Abdallah Hassan, the "Mad Mullah" of Somaliland, the British forces were restrained from crossing the frontier with Somaliland to capture him for fear of the impact this would have on other Somalis or on other European powers that also had claims to the area.

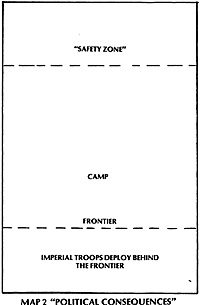

A possible reconstruction of such a situation would be to

have a board divided into three sectors. The frontier line runs

across the lower quarter of the board, the potential combat

zone occupies the central portion of the board covering half

the area, and another line marks the "safety zone", the

farthest limit the Imperial incursion can safely advance, runs

along the last quarter of the board (see Map 2).

A possible reconstruction of such a situation would be to

have a board divided into three sectors. The frontier line runs

across the lower quarter of the board, the potential combat

zone occupies the central portion of the board covering half

the area, and another line marks the "safety zone", the

farthest limit the Imperial incursion can safely advance, runs

along the last quarter of the board (see Map 2).

The Imperial patrol deploys on its quarter behind its side of the frontier. The raider's camp is somewhere in the center half. If he has his camp near the frontier he will have an earlier warning of the patrol's advance, so all or most of the patrol must be placed on the board. The number placed on the board decreases the closer the camp is to the "safety zone", indicating the difficulties of monitoring the other side of the frontier from a distance.

In crossing the frontier the Imperial patrol must inflict a certain percentage of casualties on the raider, while maintaining a minimum percentage of its own force intact. Killing or capturing the raiders' leader would be worth, at the most, half the raiders' force in points. However, if the raiders retreat across the"safety zone", casualties incurred behind that line are counted at half value.

Casualties sustained by the Imperial troops across that line, or from troops inside the "safety zone" firing out, count double. (The reverse is the case if the patrol is pursued while retreating across the frontier.) The justification for this is that the immediate area around the frontier is a bufferzone. Fighting in that area does not constitute a direct threat to the people across the frontier.

Thus, if Imperial troops manage to kill or capture a raider within that area, or disperse his force, it is a "salutory lesson" to those who might otherwise be inclined to join him. The Imperial troops have effectively neutralized the raider on his own side of the frontier. But to carry the battle too far into the opposite camp is threatening an invasion and solidifies opposition. The raider, as long as he survives' increases his support on his own side of the frontier because of the blundering ineptitude of the imperial commander in making ineffectual threats that do not demonstrate his power, but merely enrage those who are threatened.

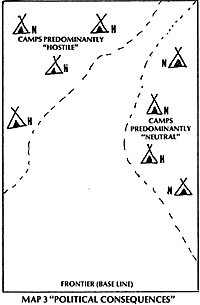

One can extend the idea of the buffer or neutral zone. The entire border region can be a "no-man's land" inhabited by hostile and neutral or semi-neutral communities. A raid carried over the border could, if mismanaged, antagonize a neutral group and send it into the hands of the enemy. An Imperial force crosses over the border (his baseline).

Scattered all over the board are villages, camps or watering holes, only some of which belong to the enemy. The patrol must hit only those that do belong in enemy hands, otherwise it will bring the neutral population out against it.

One way of having some idea which are neutral and which are not is to include "friendlies" in the patrol.

If a quarter of the force is made up of "friendlies", then the commander

will know which area of the board is predominantly hostile

and which is predominantly neutral (there may be one or two

of each mixed up in each area - See Map 3). If half the force is

made up of "friendlies", then the commander will know the

exact location of one hostile and one neutral camp, in addition

to the general feeling of the areas. If two-thirds of the force are

"friendlies", then the commander will know all except two of

the camps, and it is up to the discretion of the opposing

commander whether the remaining two are both hostile,

neutral or one each.

FRONTIER (BASE LINE)

MAP 3 "POLITICAL CONSEQUENCES"

If a quarter of the force is made up of "friendlies", then the commander

will know which area of the board is predominantly hostile

and which is predominantly neutral (there may be one or two

of each mixed up in each area - See Map 3). If half the force is

made up of "friendlies", then the commander will know the

exact location of one hostile and one neutral camp, in addition

to the general feeling of the areas. If two-thirds of the force are

"friendlies", then the commander will know all except two of

the camps, and it is up to the discretion of the opposing

commander whether the remaining two are both hostile,

neutral or one each.

FRONTIER (BASE LINE)

MAP 3 "POLITICAL CONSEQUENCES"

To reverse the position, a raider crossing the border may want to hit a village or herd belonging to "collaborators", but he would not want to antagonize those still neutral. There would be no question of using "friendlies", but he could use spies. He could use a certain percentage of his total set-up points to be spent on information from spies, rather than men.

The amount of information he would get from the spies would correspond to the information an imperial commander gets from "friendlies", depending on the proportion of points he spends on spies. I n either case, attacking the wrong camp would not automatically mean losing the game. But the points allotted to that camp would be subtracted from the total points of the attacker at the end of the game.

Conclusions

These, then, are some ways in which a frontier could impose limitations on the set-up of battles that would require a judicious use of troops by both commanders to achieve their objectives. As the objectives in many ways lie off the board, these battles do not depend on seizing and holding ground. The numbers of men involved on either side would not be large. The number of figures, however, could be the same as any standard wargame. Instead of having a figure represent 25-30 men, it would represent no more than 1-5 men.

Thus a company could be represented by 120 to 240 figures. The composition of the forces would also be different from normal colonial battles. The Imperial side would have to use more askaris than usually appear on colonial wargames. Artillery would be absent and machine guns rare. Native forces would tend to have a higher proportion of mounted men and rifles than usual. The balance of power would be shifted slightly from that in normal wargames; but then, these are not normal wargames.

More Campaign Ideas

-

Colonial Wargame Campaign Ideas: Introduction

Colonial Wargame Campaign Ideas: Wargames of Survival

Colonial Wargame Campaign Ideas: Frontiers and Wargames

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. V #3

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1984 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com