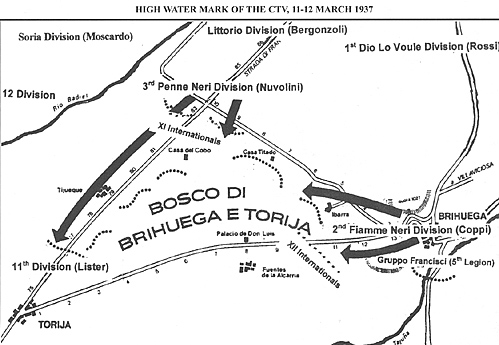

On the 11th there were finally two reinforced C.T.V. Divisions confronting what were mainly two International Brigades. The 3rd Division supported by most of the Ragruppament Raparti Specializata (RRS) and an uncertain number of batteries attacked through the snow flurries down the Caraterra against the XI Internationals, composed of the Thaelmann Battalion, Edgar Andre Battalion (both German) and Commune de Paris (French, of course) Battalion. It had its own 77-mm battery, probably the German WWI “Whiz-Bang.” It is not clear how many if any of the reserve artillery “Gruppos” had reached striking distance. The C.T.V. were not early risers, but, attacking around noon with flame throwing tanks in the lead, they succeeded in taking Trijueque.

At the same time, the Fiamme Nere (2nd Blackshirt) moved out of Brihuega towards Torija and advanced about 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) and seized the Palacio d’Ibarra from Lukacs’ elite XII Internationals, a much stronger force than the XI Internationals. It had the Garibaldini (Italian), Dombrowski (Polish) and Andre Marty (French) battalions as well as a small battery of infantry guns and a 20mm AA battery. But the Fiamme Nere apparently slipped through the woods and seized the Palacio with a short fight.

In spite of the snow, a squadron of SB-2 Bombers managed to sweep in and attack motorized reserves and trains of the Penne Nere behind the fighting. These twin engined monoplanes had similar characteristics to the U.S. commercial DC-2 and DC-3 (military C-47) transports or the early marks of the Martin Baltimore bomber. Thus western observers were inclined to call them the “Russian Martin” (thought the designs were entirely different.) They had a maximum speed of perhaps 260-mph. That made them really fast bombers in this transitional era. Nine CR-32 fighters attempted to engage them, but without success. These fighters, like the Russian I-15s, could manage 220mph or so.

By evening, however, reinforcements sent by General Maija had arrived in some strength. This included the 1st Bis (another spin-off of the famous 5th Regiment), 65th (Carabineros-Border Guards) and 35th Brigatas Mixtas, two 114mm batteries, a cavalry squadron and some fortification battalions whose armament is uncertain.

The IV Corps was established under LTC Enrique Jurado (most Spaniards on both sides were working above their pay grade at that time.) The battered 12th Division, still under Col. Lacalle faced the Marzo Brigade over the Badiel, and included the 49th, 50th, 71st and 35th Brigades. Major Enrique Lister’s 11th Division was set up initially with the 1st Bis, XI International and Movil de Choque Brigatas (Mixta was perhaps optimistic considering the lack of significant organic artillery assets. ) Major Cipriano Mera (unusual in that he was an anarchist in an increasingly communist army) commanded the 14th Division responsible for the Tajuna sector, essentially stopping the offensive in the Brihuega Sector while Lister held the Caraterra.

In the critical fighting to come, the XIIth Internationals and possibly the 70th Brigata were assigned to the 11th, but would fight in the 14th Division’s Tajuna sector. Only the 65th (Carabineros) are clearly under Mera.

Jack Radey [8] reports that Lacalle (12th Division) objected to reporting to a mere Lieutenant Colonel and was quickly replaced by one Ltc. Herero, who requested permission to withdraw if things went bad, leading to his replacement by Nino Nanetti, an Italian Communist who had commanded the 35th Brigade. Even as the command situation was being squared away, the Republicans planned a counter-attack on Trijueque for the 12th of March.

On the 12th both sides intended to attack on the Caraterra. But the C.T.V. got off the dime first. This put the Republicans on the defensive, and they were being roughly handled by the Penne Nere and RRS until rescued by massive air attacks. CR 32 fighters bounced one such attack, but succeeded only in damaging two I-15s.

Italian (other than Garibaldini) observations on the fighting of the 10th and 11th of March are interesting. Caiti and Pirella’s account [1] seems to place the seizure of Brihuega a day early. It then notes: “..on the same evening six BT-5s set up an ambush in the outlying forest. No sooner had the Third Italian Division supported by two tank companies and the armored car company begun its movement at dawn the next day than it fell into the trap. The Soviet tanks fired their cannon and machine guns at nearly point blank range. They destroyed two tanks and inflicted many casualties. The Lancia armored car company functioning as a reconnaissance unit also suffered heavy losses-at least three of its vehicles were captured and used by the enemy.”

Date Confusion

The anecdotes probably reflect actual reminiscences and/or unit records. Very likely the tanks in question, as well as the casualties noted for the next day, were real enough. But I would suggest that there was confusion on dates. However, as noted, Zaloga [2] has the first BT-5s arriving on the Cabo San Agustin 10 August 1937. Moreover, while we know that Maija had dispatched Pavlov with all the T-26bs he could put on the road, these were unlikely to be scattered about in outpost positions. However, Pavlov’s command did include Soviet armored cars, both the light scout FAI machinegun cars, and the BA series which mounted the same turret and guns, in most cases (some reported at 37mm versus 45mm) as the T-26b and BT-5 tanks. Road marches by the Pavlov’s command turned out to be the most effective anti-tank weapons the C.T.V. had at its disposal. It is therefore likely that while the tanks were laboriously brought forward and distributed for counter-attacks, handfuls of cannon armed armored cars, faster and less vulnerable to road damage, supported the advance Republican elements with anti-tank ambushes.

By the 12th of March it was no longer a question of anti-tank ambushes. Pavlov had most of the rolling armor of Republican Spain, at least the Russian T-26b elements, on the scene. There has been a lot written about the failure of the Russians in Spain to use massed armor. But if the tanks were spread out in “penny packets,” the packets tended to be located in the sector of greatest need. From the 12th on, Russian tanks, usually in two or more companies, supported the attacks towards Trijueque and Brihuega.

If the 3rd Division and the RRS got the better end of a draw on the 12th, at least until they were hit by masses of aircraft, they were (especially the Penne Nere) losing their morale. Traffic jams and enemy aircraft had made re-supply difficult. Rations were running out. The Fiamme Nere attacks on the Brihuega-Torija road were no more successful. There were now real Russian tanks on the Caraterra. The C.T.V. prepared to bring forward the reserve divisions. Littorio would replace Penne Nere at Trijueque. Dio Lo Voule would move up to Brihuega and relieve Fiamme Nere. Unfortunately troops of the Penne Nere pulled back almost as soon as they heard relief was coming, and instead of Littorio taking up their positions, the latter were overrun by Lister’s troops led by Pavlov’s tanks in the early evening. Trijueque was retaken along with 12 guns, 2 AA guns, and a great deal of less impressive booty. Roving Russian tanks reportedly [8] shot up a reserve battalion of the Penne Nere. Most of the division simply made for the nearest trucks and departed. Littorio did come up, and check the advance of Lister’s 11th Division. It may have briefly retaken the town. But by the next day (the 13th) it was firmly in Republican hands and Littorio was positioned just to the north holding the road.

There were five Republican air attacks on the Trijueque front that day and a raid by Italian SM-81 bombers. It was intercepted by I-15s, but they accomplished nothing, and one of them was brought down by defensive bomber fire. This also marked the beginning of the famous propaganda efforts by Luigi Longo and Pietro Nenni (future leaders of Italy’s Communist and Socialist Parties). They used sound trucks and their own and prisoner’s speeches to persuade CTV troops to surrender. Relatively few seem to have done so-probably less from courage than from fear of what the enemy might do to them if they surrendered.

Dio Lo Voule had an easier time of the transition. It was able to occupy Brihuega, and the bridgehead over the Tajuna seized by Francisci, as well as the famous Palacio De Ibarra. However, the bridgehead and Brihuega were dominated by wooded hills, and the raw Blackshirt recruits were under constant pressure from the XII Internationals in the Bosque de Brihuega.

This period was described in Miaja’s report [3] as follows:

“2rd Phase. March 13, 14, 15, 16 and 17 (balance): Our forces gained cohesion, stopped the enemy’s advance and launched local counter-attacks which gave us the initiative and resulted in the defeat of the first contingents of Italian troops and the occupation, among other points, of Trijueque, Palacio de Ibarra, Valdearenas and Morenchel”.

In effect, while the fronts were stabilized, the battle was slipping decidedly in Republican favor. The trucks and positions of the C.T.V. were being constantly bombed and strafed. The Dio Lo Voule Division lost control of the Palacio, and with it most of a battalion. It isn’t clear how much of the massive C.T.V. artillery force was able to establish itself in useful positions. But the smaller Republican artillery forces, whose guns and trucks were not under constant air attack, were going into position and stockpiling ammunition. In place of the armored car vedettes Pavlov had 40-60 tanks on hand more or less in running condition. Russian planes attacked both the front and the truck convoys, demoralizing the troops and exacerbating logistic problems.

Shifting Priorities

On the 16th the air attack priorities shifted to Brihuega where the Dio lo Voule had replaced Fiamme Nere in the lines. Francisci’s 5th Regiment had also withdrawn. The bridgehead over the Tajuna was now held by the 6th Regiment left over from the Fiamme Nere Division. The tankettes had proven unable to penetrate the Bosque de Brihuega, and there is no evidence that the two companies which had supported the 2nd Division remained. The RRS was on the Caraterra with Littorio. The Reggia Aeronautica, flying two weary squadrons of CR 32 fighters from unimproved fields at higher, often socked in, elevations, was unable to assist. And the Dio lo Voule (1st Blackshirt) division seems to have lacked the four gun battery (reported by the Air Attaché as six guns) [15] of Breda 20mm automatic anti-aircraft guns of the other divisions.

Government (Republican) sources [14] : “The enemy positions at and around Brihuega were bombed this morning by twenty-five heavy bombers. They discharged 760 bombs with a great deal of accuracy. Immediately after this action 30 pursuit flying in three groups attacked enemy concentrations in the same sector. The pursuit dropped 120 bombs and fired an extremely high number of machine gun bullets.“

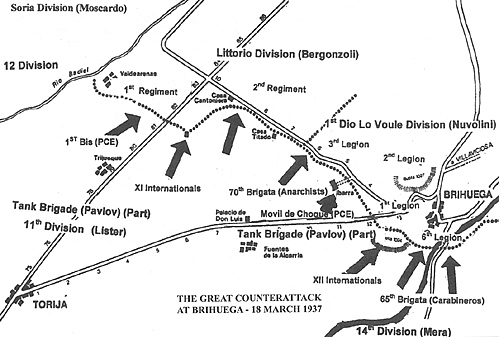

On the 17th of March the weather was so bad that it prevented even the Republicans from making air attacks (This is contradicted by another report that indicated 90 Republican sorties.) But the ground forces of the facing Brihuega, which by then included the fresh Movil de Choque (Communist) and 70th (Anarchist) Brigades, the veteran XII Internationals, and the professional 65th (Carabineros) were lining up on the wooded hills overlooking Brihuega and the Tajuna Bridgehead from the south. They were probably supported by 2-3 “Gruppos” of artillery, but more importantly by 30-40 tanks.

The command situation was a bit strange. Maija wanted Pavlov (The Russian tank commander) to command the battle of Brihuega. The fight was in the Tajuna valley, hence in the 14th Division area. But brigades moved back and forth between the 14th (Lister) and 11th (Mera.) Jack Radey [8] prefers the version in which the 70th and Movil de Choque, which were fresh, were on the Republican left, and intended to swing north of Ibarra’s Palace, cutting off the possible retreat of the C.T.V.. That plan was developed by Col. Rojo of Maija’s staff. It would be executed across divisional command lines. Next were the XII I.B. and then, with one battalion on the west side of the river, and the rest over the Tajuna, were the 65th Brigade’s Carabineros.

On the afternoon of the 18th the attack went in. It began with a bombing attack in early afternoon by two squadrons of light bombers (R-5 and RZ biplane attack aircraft). “A little later another bombing squadron escorted by 45 pursuit craft (roughly 4 squadrons) repeated the attack over the same positions but with much greater intensity.” This was followed by artillery fire and the advance of four “Brigata Mixta” supported by 30-40 tanks against four regiments, or “Blackshirt Legions” lightly dug in and somewhat shell-shocked. Elements of two 75mm Gruppos, two 100mm Gruppos, and the IV 149mm Gruppo supported the defenders. The results are confusing. Some accounts suggest that there were only a few defending battalions and they offered little or no resistance after the fierce air attacks. But that was far from the case.

The 6th Blackshirts were quickly tumbled over the bridge by the Carabineros, and the 1st Blackshirts were successfully attacked by the XII Internationals and some companies of Pavlov’s tanks, the latter killing the Colonel and most of his staff, and apparently taking out the regimental guns displaced forward in an anti-tank role.

[8]

But the 70th and Movil de Choque supported by two companies of tanks were held up by the 2nd Blackshirt Regiment dug in on ridgeline west of town and the 3rd Regiment to the northwest of town. The 70th (Anarchists) and Movil de Choque (Spanish Communists) variously claimed credit for the victory. But it seems to have been won by the XII I.B. and the 65th Carabineros, with a little help from Pavlov’s tankers and their friends in the Air Forces.

Covered by the 2nd and 3rd Regiments, the Dio lo Voule Division followed their Division HQ pell mell to the north around 7:15pm, with the town and some loot falling into Republican hands by 8pm. The airplanes had been invaluable. But there had been hours of serious ground combat. And, contrary to some rumors, the hottest fighting was not between the 65th Brigata Mixta and Movil de Choque over custody of captured C.T.V. trucks.

On the Caraterra things were a bit different. Notionally the Brihuega fight was conducted by the 14th Division (Cipriano Mera) of the 4th Corps. The Trijueque sector on the Caraterra remained under the control of the 11th Division (Enrique Lister) while the battered 12th Division skirmished with the Soria Division over the Badiel. But the 11th Division seemed to have little on hand but the worn out XI I.B. and the 1st Bis (like the Movil de Choque, a spin off of the famous 5th Regiment.) They were counterattacked by Littorio, which almost split the two brigades and seemed on the point of rolling up the entire 4th Corps from behind. This threat was checked at the crucial moment by the division commander. Lister managed to come up with two battalions and two companies of T-26b tanks. Attacking the right flank of Littorio’s advance he threw them back to their start lines.

Littorio, probably with remnants of the RRS, held on until advised by General Rossi of the 1st Blackshirts that the latter were in full retreat. Then Bergonzoli conducted an orderly withdrawal up the Caraterra. Lister was undoubtedly more than happy to see him go. The overall Republican pursuit, by accident or design, was leisurely. One is almost reminded of Kutuzov, who, when told that Napoleon’s troops were escaping, suggested that the Russians should “Build him a golden bridge!”

Fortunately for the C.T.V. they had only to fall back a few kilometers in a cold rain rather than trudge across a thousand or so in the dead of Russian winter. There were air attacks on the roads and even the railroad lines at Siquenza. But by the 20th of March the C.T.V. and their Soria Division allies were dug in on lines nobody seriously wanted to take away from them. One of the main reasons for a lack of pursuit was exhaustion of both men and material on the Republican side. Pavlov’s tanks, which, with the Red air forces were crucial to the victory, had shot their bolt. The T-26bs were lacking in patriotism. While perhaps 9 C.T.V. tanks and 9 of Pavlov’s were put out of action by direct enemy action, Pavlov was down to 9 runners due to extensive road marches and short but damaging movement in the rocks and mud. Several CV 33s fell into Republican hands because, in spite of the short distances in the campaign, they had burned up too much fuel in the mud too far from their gasoline supplies.

In the end, the C.T.V. got little sympathy from the allies it had come to help. Jack Radey [8] quotes a ditty believed to have been composed by a Spanish Nationalist Liaison Officer: ‘Espana no es Abysinnia, los Espanoles, aunque rojos, son valientes, menos comiones y mas cojones”. In English : “Spain is not Ethiopia, Spaniards, though Reds, are brave, less trucks and more balls.” The feeling dies hard. A few years ago when I was already in Maryland for the summer my wife was entertaining a group of foreign visitors to the local wildlife park where we volunteer.

One Spanish gentleman was intrigued by some painted CTV figures on a shelf. When he asked and was informed (and I thought all toy soldiers looked alike to my wife!) of their identity he snorted. Then he said: “Those Italians--they came to Spain unwanted, chased our women, and ran away on the battlefield.” That after 60 years!

One U.S. paper [11] commented on the possibility of cavalry in the exploitation. There were 50 sabers attached to the XII I.B., and several squadrons under Jesus Hernandez (a strange name for a Communist, but I once knew an F.B.I. agent named Karl Marx Burtram.) It is tempting to imagine squadrons of Republican cavalry sloshing over the hills to intercept and harass the demoralized C.T.V. much as Monasterio’s troopers plagued the retreat from Teruel in early 1938. But they were apparently fully occupied against the Soria Division. Moreover, the most popularly reproduced maps in the U.S. are misleading. The C.T.V. advance, and much of the retreat, occurred on the Caraterra and a secondary road (not shown on our maps) which reached over to the Palacio de Ibarra and Brihuega. The U.S. maps showed the two Italian axes of advance as the Caraterra and the Masegoso-Brihuega main road, leaving a wide open area for cavalry exploitation. But in that wide open area were elements of several C.T.V. divisions. And the Republican horse troops often lacked even supporting machine guns, let alone mortars or other weapons which could have assisted in cavalry attacks.

The C.T.V. offensive had gained a little ground, and it is uncertain who actually lost the most manpower in the brief campaign. But it effectively shattered the C.T.V. corps that had been assembled for the glory of Fascist Italy. After the survivors rallied on the new line Roatta, the overall commander was relieved. Two Blackshirt Divisions, the 1st Dio Lo Voule and 3rd Penne Nere were disbanded. Fiamme Neri had been badly chewed up, but was retained.

Since Console Francisci had fought well, his 5th Regiment spearheading Fiamme Nere and the 4th Regiment holding Masegoso (admittedly with little threat from the Republican 72nd Brigata-which could be said to have equally held the 4th Blackshirts) it became the basis for a new Blackshirt Division, XII de Marzo. Littorio was retained, and the RRS elements, badly shot up, were reassigned, re-equipped, and brought up to strength. By the end of the war only Littorio and three Spanish-Italian divisions (Frecces (arrows) of various hues) remained.

An interesting listing of the evolution of the C.T.V. during the war is offered by Mark Hannum on the GAUNTLET web site. [17]

It will prove a bit confusing, because at the outset the C.T.V. arrived in bits and pieces, and was formed into “Banderas” (battalions) and “Gruppos de Banderas” (regiments.) Notionally these were elements of the Spanish Foreign Legion (Tercio). However, by March 1937 the Gruppos de Banderas had become “Blackshirt Legions” (Regiments) each with three “Blackshirt Cohorts” (battalions) a battery of 65mm infantry guns, a 45mm mortar platoon and some odds and ends which were hastily formed into divisions as described.

Map: High Water Mark

Map: Counterattack

The Spanish Civil War The Guadalahara Offensive

-

Introduction

Organization of the Italian Forces

Enter the Red Air Force

High Tide of the C.T.V.

Gaming Guadalahara

Tactical Organizations

Modeling the Guadalahara Campaign

Bibliographical Notes

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #84

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com