Polikarpov R-5 follows SB-2 Bomber over Brihuega in the 18 March 1937 Republican Counter Attack.

The original uprisings had been followed by a war of mobile columns then set piece battles. The air war had passed through several stages. Madrid had been narrowly saved by loyalist troops, paramilitary, workers militias, and increasing contingents of foreign volunteers. A subsequent “Rebel” offensive, backed mainly by the Army of Africa, had bogged down on the Jarama front. But as yet no major contingents of foreign troops had intervened on either side.

In the first months of 1937 (beginning 8 February) a combined force of Spanish “Rebels” and Italian Fascist volunteers (C.T.V.) took Malaga. The defenders of Malaga were poorly organized militia units with no air or anti-armor capacity to speak of. The brigade sized Italian force included “Carro Veloce” (C.V.) 33 tankettes mounting two 8mm machineguns with two man crews and from 6 to 13.5mm of armor. Not much, but irresistible to raw militia with rifles. This success doubtless confirmed the Italian command in the notion that the C.V. 33s were main battle tanks in that day and time. The problems encountered around Madrid, where real tanks (Russian T-26bs) had appeared were not taken as seriously as they might have been.

Building on the success in the Malaga offensive, Mussolini sought a more public and impressive triumph for Fascist arms. After a conference in Rome, General Roatta began to organize a strong corps for an all C.T.V. offensive. This idea was not immediately popular with General Franco. He held strong convictions about the political importance of winning with Spaniards. But with the stalemate on the Jarama he grudgingly accepted Mussolini’s kind offer. The result would prove immensely satisfying not only to Franco and the Spanish “Rebels,” but to their Spanish Republican opponents as well. It would be much less satisfying to the C.T.V. and its home Government.

Campaign Critique

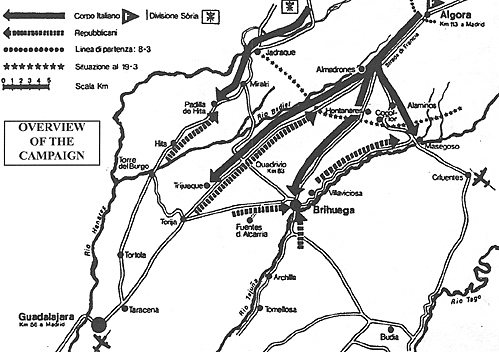

The campaign, which opened with a thirty minute C.T.V. artillery barrage on 8 March 1937 and had fizzled out by 21 March 1937, got mixed reviews.

The most important impression it gave was of the importance of attack aviation. French observers, and to some extent Germans as well, drew strong conclusions about the effectiveness of ground attack by fighters and light bombers. The French, who had been focused heavily on independent strategic bombing, reconsidered. Plan V of 1938 turned its back on the “Big Ugly Fellows,” large heavily armed “Multiplaces de Combat,” and under it France set out belatedly to build and buy fighters and attack planes. The Germans may also have noticed that the destruction of Guernica later on produced mainly bad press, while the Russian air attacks on the C.T.V. on the road to Guadalajara were actually militarily useful-and nobody complained.

The U.S. Army Air Corps studied the campaign with interest. Our Attaché to Valencia (Republican Spain) forwarded tons of material, the first batch of which got lost in the State Department, leading to some critical comments from the War Department. The Attaché was an infantry officer who thought properly trained infantry wouldn’t have been as badly affected. But many U.S. accounts, based heavily on the Assistant Attaché for Air’s reports and subsequent articles, gave most of the credit for the repulse of the C.T.V. to aviation alone. This wasn’t enough to distract Air Corps Chief “Hap Arnold” from his strategic agenda. But it had an effect. The British, of course, didn’t seem to notice at all.

Italian impressions varied. The C.T.V. drastically reorganized and made some command changes. Colonel Amadeo Mecozzi, an opponent of Guilio Douhet, the high priest of strategic aviation theory (and Godfather of the French “Big Ugly Airplane” fetish) used the Guadalajara debacle as a major case in point. To him the decisive aircraft of the next war would be a fast fighter-bomber. Later on an article in Armor Magazine (May/June 1986) [1] described the fight in terms of heroic Italian crewmen who won often posthumous medals trying to close with BT-5 tanks in C.V. 33s, both machinegun and flame thrower versions. That there were no (Steven J. Zaloga Tank Operations in the Spanish Civil War) [2] BT-5 tanks in Spain until August 1937 should not be held against them. A 45mm AT shells from any source tend to look alike when you are driving a C.V. 33.

On the other hand the official reports from the Republican General Staff (extracts of which were obtained by the U.S. Military) [3] saw the campaign as a triumph of the fledgling Popular Army over its Italian Fascist enemies. The Spanish “Rebels” enthusiastically agreed.

And for the COMINTERN and fellow travelers, it was, of course, a tangible triumph of the International Proletariat over their Fascist Oppressors.

The truth contains elements of all the above.

In a 1939 edition of his textbook “MANUEVER IN WAR” Colonel Charles A. Willoughby (EB, THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR, AN AMERICAN MILITARY PERSPECTIVE 1992) [4] had this to say:

“The operation on the Aragon front, known as the Battle of Guadalajara deserves more attention than it has received. It represents the decisive intervention of air craft against motor columns and stands as a warning of the constant menace of air attack in modern warfare.”

“The Aragon front had remained a “quiet sector” until 8 March, when two Insurgent (Italian) divisions started a drive against Guadalajara; until 17 March only hasty Government reinforcements were available; in the meantime (specifically on 12 March) the ensuing battle was fought and won by air operations.”

“Concentrated on the line: La Tobe-Algora, the 2nd Division encountered little resistance on this quiet front and advanced via Gajanejos in 36 hours. One day, the tenth, was lost waiting for the 1st Division advancing to the east. This delay was due to the obviously poor road net: Almadrones-Brihuega. The weather turned cold and rainy. The elevation of this inhospitable section of Aragon is over 3,000 feet. On the eleventh, the long lines of motor trucks weathered a heavy storm by being tied to their paved routes; it was this column of about 1,000 vehicles that became the target for Russian attack aviation the next day.”

“It must be noted that the terrain was ideal for an air attack; a barren treeless plateau of 3,000 feet elevation with a single narrow paved highway running in an almost straight line from Torija to the north; the adjacent ground was waterlogged and very muddy. There was no evidence of anti-aircraft protection in the 20 km column and the troops were not skilled in defensive measures.”

“The Government assembled approximately 100 planes at the airdrome of Alcala-de-Henares, primarily Russian planes and Russian pilots; the composition of this striking force was as follows:

Note: Based on Howson’s AIRCRAFT OF THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR. [5]

The Polikarpov I-15 with four rifle caliber MG had a speed of 215mph, which is rated slower than its principal opponent the CR 32 at 219mph (two 12.7mm MG) but with a slight edge in climbing and turning. The same source gives the Polikarpov I-16 Type 5 monoplane a speed of 281 mph. The latter had only two rifle caliber MG, but they were of a later type with twice the rate of fire. The R-5 “Rasante” biplane was so-called because of its downward firing 4 MG main armament (described in Military Attaché Valencia Report 6520 [6] ). The attaché rated the R-5 at 130mph, which tracks with 150mph for Howson. The attaché also reported a new version coming out with a 150mph speed, which was almost certainly the R-Z Natasha, and up-engined model he rated at 150mph as opposed to Howson’s 178mph. At least a squadron of each was employed in the Guadalajara campaign. The Katiouska was actually the SB-2, which Howson rates at 262 mph. It had two forward firing and two rearward firing MG. The principal Italian bomber present was the Savoi Marchetti SM 81 with 6 MG and a claimed speed of 210mph, of which Howson is skeptical. They do not appear to have attacked Republican ground troops until after the fall of Brihuega on 19 MAR 37.

“Apparently the bad weather prevented effective counter-operations by Insurgent planes; the extraordinary optimism of the column commander may have been a contributing factor.”

“On the twelfth this mass of aviation was launched in a surprise attack, under cover of low ceiling and heavy clouds, all planes flying low. The 2nd Division was caught strung out over 20kms along the highway at Saragossa.”

“The attack was staged in successive waves:

“The I-16s were initially on protective missions, but emptied their machine guns into the columns, toward the end of the action...The motor column was stopped in its tracks, lack of lateral roads and the vile weather making escape or deployment impossible. Panic swept the command. An eyewitness reported “..along the straight highway, telegraph poles are blown up and the wires flutter like tendrils; everywhere demolished trucks and cadavers..”

“On the sixteenth the attack turned against Brihuega, in which the Italian 1st Division had found refuge; thirty R-5s and I-15s operated against this locality. On the eighteenth, Government infantry units made their first appearance and took Brihuega. The Italians withdrew via Almadrones. This movement was picked up on the nineteenth and 80 planes attacked with 600 bombs, and fired 100,000 rounds. By the twenty-first, the Insurgents were driven once more behind the initial line of departure.”

Interesting, but not entirely accurate. The Republicans had troops on the ground from the beginning, of course. While the Siquenza/Guadalajara area was a secondary front prior to 8 March, it was held by the 12th Division of the fledgling Popular Army. Reinforcements poured in beginning with the night of the 8th. Before the air attacks developed any strength, indeed, before the Italian motor columns were discovered from the air, heavy ground combat had developed.

More surprising, while Willoughby discussed the Italian (C.T.V.) 1st and 2nd Divisions, there were more. Curiously, on the 10th, north of Brihuega in a wooded area called the Bosque de Brihuega, a staff platoon accompanying the Major Commanding Littorio Division’s Machinegun Battalion was reconnoitering positions where it was to support elements of a the Penne Neri (3rd) Blackshirt Division. While wandering around it was bagged by some very capable Italian speaking soldiers who seem to have belonged to the Assault Platoon of the famous Garibaldi Battalion of the XIIth International Brigade. The major (Luciano Antonio) and several other prisoners proved talkative. Among other things they told their captors:

“Lieutenant Aquile:..The head of all Italian forces is called Machinoy. ...He (Aquile) belongs to the Littorio Division. On this date (i.e. when captured) he was on the way to join the Nuvoloni Division. This division has eight or ten thousand men. There are four Divisions, three of them are black shirts and one of the army. The division has two regiments and each regiment three battalions of four companies, three of which are fusiliers and automatic rifles and the fourth of Fiat machineguns. The regiment has a platoon of mortars, one battery of 65.17 (infantry guns) and mortars of 45 latest model.”

“Major Antonio: Belonged to a machinegun battalion of the 1st Littorio Division and was attached to the 3rd Division (Nuboloni.) The Littorio Division was in reserve. There are four Divisions. 1st Littorio Division, and the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Divisions of black shirts. The 3rd Division is commanded by General Nuboloni, and General Bergonzoli commanded the Littoria Division, which had its headquarters at Arcos de Medinaceli. “

Actually, while not everything the prisoners said was entirely true, the Republicans, thanks to the energetic Garibaldini, had captured a lot of information about their enemies and their plans. Included in the booty seems to have been a document probably sponsored and partly written by the Division’s commander. It reached our attaches as an Exhibit in the Republican Report on Guadalajara titled “ORGANIC AND TACTICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ITALIAN MOTOR DIVISION." [7] This document is virtually an owner’s manual to the Littorio Division. However, it is clear from the text that its organization, essentially two infantry and one artillery regiments, the ill fated Machinegun Battalion, a 20mm Breda AA battery plus signal, chemical, medical and M.P. (Carabinieri) was not typical. It was fully motorized.

The motorized artillery regiment is described as having “a group of 65’17s on trucks, a second group of 75’37s on trucks and with tractors, and a third group of 100’17s.” At some point all three groups are supposed to have been of 100s. Jack Radey [8] has been exploring the issue with Italian authorities, who claim that the gruppos in the Guadalajara campaign were entirely equipped with the 65mm weapons. Both Greg Novak (Command Post Quarterly 8) [9] and Curt Johnson (Scenarios For Wargamers-Guadalajara) [10] use the 100mm standard. Since the paper on the motor division 7 was captured from soldiers thereof during the battle, I favor that version.

The other divisions were different. The 1st Blackshirt Division “Dio Lo Vuole”(God Wills It) under General Rossi, the 2nd Blackshirt Division “Fiamme Nere”(Black Flames) commanded by General Coppi, and the 3rd Blackshirt Division “Penne Nere”(Black Feathers) commanded by General Nuvolini had three infantry regiments each. They had no organic artillery except for the canon companies (as they were called in the U.S. Army) of 65mm infantry guns at regimental level. Nor were they fully motorized.

U.S. accounts derived from Republican sources (the Assistant Attaché for Air, Captain Townsend Griffiss, had so many Republican AF contacts he was accused of “Non-neutral behavior”) tended, curiously, to underestimate the C.T.V. forces involved. The Republican estimate was in fact low, but in a Paper for the Air Corps Tactical School at Maxwell Air Corps Base, the author, Lt. Mills Savage [11] , gave the following strength:

During March 1937 the Italian Fascist volunteers (Corpo di Truppi Voluntarie) conducted a short and unusual campaign. For perhaps the first time a strong motorized force supported by artillery, aircraft, and armored fighting vehicles (more or less) launched a concerted offensive. It was the eighth month of the revolt of “Traditionalist” “Nationalist,” or perhaps “Fascist” Rebel Spaniards against the Spanish Republic.

During March 1937 the Italian Fascist volunteers (Corpo di Truppi Voluntarie) conducted a short and unusual campaign. For perhaps the first time a strong motorized force supported by artillery, aircraft, and armored fighting vehicles (more or less) launched a concerted offensive. It was the eighth month of the revolt of “Traditionalist” “Nationalist,” or perhaps “Fascist” Rebel Spaniards against the Spanish Republic.

No. of

PlanesType Armament Bombs

(100lb)48 Biplane I-15 Attack 2 M.G. 2 48 Monoplane I-16 Pursuit 2 M.G. 2 24 Biplane R-5 Attack 4 M.G. 4 24 Monoplane “Katiouska” 2 M.G. 4 First - 30 attack planes: I-15s

Second- 40 mixed planes: I-15s and R-5s

Third- 45 pursuit planes: I-16s

The Spanish Civil War The Guadalahara Offensive

-

Introduction

Organization of the Italian Forces

Enter the Red Air Force

High Tide of the C.T.V.

Gaming Guadalahara

Tactical Organizations

Modeling the Guadalahara Campaign

Bibliographical Notes

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #84

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com