A Wargamer's Complete Guide to the Armed Opposition to France’s Expansion Across the Algerian-Moroccan Frontier at the Turn of the Century

At the dawn of the 20th century, an influential party of colonialists was obsessed with carving a colonial empire out of the barren wastes of the North African desert for their personal glory in the name of France. This was achieved through political manipulation and subtle subterfuge on the part of a handful of ambitious army officers. This activity led to a series of small unit actions in North Africa culminating in a full-scale invasion of Morocco in 1907. These actions are eminently suitable for colonial skirmishing on the wargames table.

In an effort to manage the size of this article we have stayed away from the political disintegration of Morocco during this period and also chosen to omit information pertaining to the occupation of Morocco proper and the rebellions that ensued. Perhaps this will be the subject of another article, as may the expansion into the southern Sahara and battle with the Tuaregs.

We will first present an overview of the theater. Describe the Invasion and battles that this precipitated. Introduce the combatants. Describe their weapons uniforms and tactics. Finally we will discuss some modification suggestions to The Sword and the Flame, particular to this campaign. We will present scenarios for this popular set of skirmish Colonial Wargame Rules, which could be adapted to other rules

References to “The Sword and the Flame” appear by kind permission from Larry Brom, their author.

At the end of the 19th century, France’s attentions in Algeria were turning south and westwards. The northern tribes had been mostly subdued and the last of the great resisters, Bou Amama had moved to Figuig across the uncharted border into Morocco, the last free Muslim State west of Constantinopal.

The XIX army corps operations were now expanding south into Algeria and the Sahara. The desert was conquered oasis by oasis. To these desert outposts, supply became a matter of life and death. The forts’ occupants were shut inside their mud brick tombs prevented by the local hostile tribes from doing little else but await the next supply column.

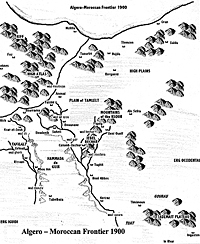

In the west, the Algero-Moroccan border was only defined for a few miles in from the Mediterranean Sea between Oujda and Tlemcen and finished just north east of Berguent. It was so defined in 1845.

South of this lay the frontier region of the Gourara, the Tuat, and the Tidikelt. France had instructed the army not to enter Morocco, but where exactly Morocco was, was not defined. Individual Kasars (fortified town or village) were stated as being either in Morocco or Algeria. The Sultan of Morocco and the Makhzan (government) had minimal influence politically in the region, and none militarily. As a descendent of The Prophet he was, however, the spiritual leader of the region. To the inhabitants of the area there was no difference between this spiritual leadership and any physical leadership. It was a failure to this that drew the French in to the conflict.

In the great Savannas south of the desert, the French were moving eastwards from Senegal in to the Chad and the region of what is now the Central Africa Republic. Although this region should be the subject of a separate article, it is important to mention it here. Soon to become French Equatorial Africa, this area was on the northern fringes of the British colony of Nigeria. Nigeria was perceived as a threat to France in this time of political trepidation following the Fashouda affair that had brought Britain and France to the brink of war.

Britain recognized Moroccan sovereignty of the Tuat. France was concerned that seizing the frontier oases this far west on the frontier would spark an intolerable diplomatic crisis with Britain. Another French motive not to be ignored was the fact that the idea of a Trans-Saharan railway had not been completely abandoned, despite the disaster of the Flatters expedition. Now that the French were on the north bank of the Niger River, a railroad would allow for the fast redeployment of French troops to the Niger where they could threaten the British colony of Nigeria in the event of war.

In 1899, Britain embroiled itself in the Boer War. The colonialists in France knew this would allow its plans to seize the oases in the Tuat go politically unhindered. So, while Britain was chasing the Boer, the French foreign minister, a staunch colonialist, hatched a plan with which to convince parliament to condone their incursion into the Tuat and the Tidikelt.

More Resistance in the Desert Part I

The Region

Introduction

Invasion of Tidikelt

The Resistance Ferments

Problems of Supply

Overview of the Inhabitants of SE Morocco

Military and Political System of Dawi Mani' and Ait Atta

Kasar Inhabitants

Native Firepower in the Desert

French Forces in North Africa

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #80

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com