The effect on the war was not the same as the way Gates' victory over Burgoyne did. Nonetheless, the British stood on the threshold in August 1780, of once again having a chance of winning the war. Effective organized American resistance was eliminated and the grand strategic plan of Clinton's could be set in motion.

Actually, it seems that Clinton had little more than taking Charleston in mind when he headed south in December 1779. This was typical of the British command throughout the war. Leaders like Howe and Clinton would dream up the beginnings of something and let it dangle. To his credit, Burgoyne at least looked a bit farther than his contemporaries.

Clinton left Cornwallis in charge of the South when resuming to New York and his orders allowed a wide latitude in interpretation. By the time of Camden, Cornwallis had implemented a plan of subduing, consolidating, and fortifying coastal areas in Georgia and Souuh Carolina. Large Loyalist detachments were used for these jobs of establishing supply posts, patrolling the roads, and generally pacifying the locals. The approach was typically methodical, an interlocking series of outposts which kept lines of communications open to Charleston as well as extending effective British control inland. By using largely regular Loyalist units, the British were also recruiting local Tories into the army, another critical factor in the decision to campaign in the south.

The plan itself, in its initial stages, was sound and well implemented. Unfortunately, it was not geared to combating an insurgency movement that in turn called into question the Crown's control of secure areas. Unless such areas were maintained, as we shall see, the British army operating inland would be cut off and ill-equipped to fight a long hard campaign.

Cornwallis felt that a secure British hold on South Carolina was obviouslv in keeping with the overall strategic aims of the southern campaign. It was also neccessary as a springboard into extending operations into North Carolina. With no organized resistance in hand and the subdugation of South Carolina well underway, Cornwallis planned on moving into the colony by the end of 1780.

While there was no organized resistance after the debacle at Camden, partisan leaders in the Carolinas were active throughout the rest of 1780 and in the case of King's Mountain, caused Cornwallis to change his strategy. In the South Carolina low country, partisan activity was lead primarly by three men: Sumter, Francis Marion, and Andrew Pickens. Between August and December 1780, they fought no less than five small battles against British forces in what could nominally be considered controlled areas.

His actions had two effects, the first was that no matter how the British tried to secure an area, partisans could undermine that authority which in turn shook any 'Neutralists' sympathies with the Crown.

Secondly, the raids and skirmishes were a constant drain on British troops and supplies, tying down assets that could have been better used elsewhere. Actions by partisan leaders such as William Davie, who operated with Sumter at Hanging Rock and on his own along the Carolinas border, also proved to slow British moves northward. Davie and Marion, two "guerilla" leaders showed their worth as military commanders in any military during the dark days following Camden.

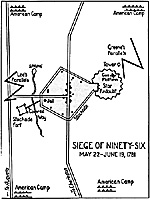

The upcountry had its leaders also, namely Elijah Clarke from Georgia, Charles McDowell of North Carolina, and Isaac Shelby from South Carolina. These three won a small, but sharply fought battle against regular Loyalists and Tory militia at Muscgrove's Mill the day after the disaster at Camden. Clarke threatened Augusta in mid-September which prompted forces to be drawn back from Fort Ninety Six to drive him off: However, the upcountry leaders had a profound affect on the southern campaign and the war overall at the Battte of King's Mountain.

I intend to discuss King's Mountain in greater detail in another article. A much briefer description will suffice here. Cornwallis' plan was to start a two pronged advance north, a sweeping movement along the Blue Ridge mountains led by Major Patrick Ferguson. Ferguson would sweep the area gathering Loyalist support (and most importantly, recruits) while Cornwallis would lead the bulk of the army northward through the Piedmont region of the state.

Although Cornwallis had misgivings about apointing a mere major to such an important task, there were pros and cons to his decision. Ferguson got along well with the natives and was a master at recruiting and training Loyalist troops. This is ironic considering the reaction by the over "mountain men" that led to King's Mountain. Ferguson's biggest problems were his huge ambition, personal frustration with the way his career had gone, and his snobish anitude toward the patriots.

Worst Thing

The worst thing Ferguson did was to proclaim that unless the upcountry partisans ceased their activity, he would march over the mountains, kill their leaders and lay waste to their land. The frontiersmen, obviously concerned by this pronouncement, decided the best clefense was a good offence. They mobilized over 1.000 men, all mounted and rifle armed - the prototypical frontiersmen used to fighting the Indians, giving no quarter and expecting none.

The second worst thing Ferguson did was allow himself to get trapped atop King's Mountain AND do nothing to fortify his position. It is almost certain he chose the site intending to wait for Cornwallis to send a relief column. He had successfully eluded the frontiersmen for two weeks and expected reinforcements. Unfortunately, Cornwallis, his second in command, and Tarleton, who had the most mobile force in the main army were both ill.

Ferguson played right into the hands of the Patriot riflemen. He insisted on having his Loyalist forces conduct repeated bayonet charges into the woods downslope from his open position atop the mountain. The riflemen continually retreated, picking off the enemy as they did so.

By not fortifying the mountain top and waiting, Ferguson gave away a singular tactical advantage. Now his units began to surrender. He tried a futile last dash charge to break out of he circle and received about 13 bullets for the trouble. In about an hour, the best laid plans of mice and Cornwallis were in a shambles.

British troop losses at King's Mountain, while not insignificant were not that detrimental to the army itself. The defeat had a major impact on the Loyalist population living outside of British control. Kings Mountain made it clear that if you waved the Union lack too vigously, you could find yourself dead. No matter how many professional Briash officers were around to organize resistance. King's Mountain also reversed the steady decline in Patriot military attitude that began with the siege at Charleston. The Bntish were not immortal, as was proved again on 20 November at Blackstocks where Sumter bloodied Tarleton with mere militia.

What amounts to the rainy season began shortly after King's Mountain. Cornwallis came down with malaria and much of his army was sick and roads became quagmires. His correct perception was that the western half of North Carolina was hostile and could not be subdued. Considering the state of his army, he went into camp in Winnsboro, NC, doing nothing until the beginning of 1781.

The lack of "organized" Continental resistance, which was the result of the debacle at Camden, was changing. Nathanial Greene was placed in command in October. Greene's main responsibility under Washington was that of a logistician, a task at which he excelled. He needed it when he saw what little was left to him in the South.

Greene wisely saw that his army was in no shape to meet Cornwallis on the battlefield, it needed time to resupply and reorder itself. At the same time, fresh from Patriot successes at King's Mountain, Greene wanted to impress upon the southern population of the Continental army's ability to carry the attack to the enemy.

Daring Plan

In what has been praised as a daring, yet imaginative plan, Greene simultaneously withdrew to Cheraw, SC, a site better suited to support his battered army, and sent Daniel Morgan with a small core of Continentals and what little dragoons left to him south.

In what has been praised as a daring, yet imaginative plan, Greene simultaneously withdrew to Cheraw, SC, a site better suited to support his battered army, and sent Daniel Morgan with a small core of Continentals and what little dragoons left to him south.

Greene's orders to Morgan were deliberately broad. Morgan was to link up with militia forces and harry Cornwallis' lines of communication and threaten Fort Ninety Six.

Before going on to Morgan's quick campaign which resulted in the battle of Cowpens, we need to look at one other important decision Greene made, namely to try and support the Patriot partisans operating in South Carolina. Almost immediately upon taking command, Greene detached probably the best unit in his army at that point, Lee's Legion, commanded by Henry Lee, the father of Robert E. Lee. Lee hooked up with Francis Marion and the two complemented each other well.

Off and on over the next six months, their combined operations played havoc in areas supposedly controlled by the British. While not harmful in an immediate operational sense, the Marion/Lee team once again made it clear to the populace that the British could not be expected to protect them.

Now back to Morgan. He followed his orders quite well. Although he was in no position to actually besiege or assault Fort Ninety Six, raiding parties led by Col William Washington commanding the dragoons in the army, were very succesful hacking up numerous Tory militia parties. Washington's raids were so good that some of his mounted militia took a small stockade just 15 miles from 96. While not hanging around to admire the scenery, the frantic overstated reports from the local commanders to Cornwallis indicated that 3,000 American troops were threatening 96 at Christmas.

Cornwallis was forced to act. He split his army into 3 groups, one under Tarleton to hunt down Morgan, a second was left at Camden under Francis Lord Rawdon in case Greene decided to move from Cheraw, and Cornwallis led the third roughly north to position itself between Morgan and Greene.

Faulty intelligence, poor communications, and bad weather hampered the British operations leading up to and right after Cowpens. Yes, Tarleton was succesful in discovering that Morgan posed no threat to 96 and he eventually tracked the Old Wagoner down for a fight. However, he was never accurately aware of Cornwallis' movements and vice versa.

The Chase

It was not until 5 January that Tarleton actually began chasing Morgan and Cornwallis did not begin his march until the 8th. Both forces were bogged down by rainy weather and its affects on the roads. Cornwallis assumed that Tarleton was having the same marching problems as he and although the impetuous British Legion commander was slowed a bit, he was right on Morgan's tail. Morgan was doing his best to not be trapped between two British forces. Although Morgan was to later defend his place of battle, he was doing his level best to avoid fighting at all and if forced to do so, not on Tarleton's terms.

By 16 January, the cocky Brit, who had felt that Morgan would not actually stand and fight, finally had the Americans in a position to either attempt a risky flooded river crossing with a threatening enemy to the rear or fight.

Morgan appears to have judged the character of his opponent very well. Morgan arrayed his troops to optimum advantage and counted on Tarleton's impetuosity to play into his hands which he did. While Morgan carefully explained everything to practically his entire army, allowing it to rest and eat, Tarleton was marching all night, taking no time to halt or even restrain his approach in time for his subordinates to effectively order the line of battle.

Morgan beat the pants off of little "Benny", once again throwing Cornwallis's plans into disarray. My favorite character, Robert Kirkwood commanding the remnants of the Deleware Continentals put it succinctly in his journal: "17 January, Defeated Tarleton."

For the second time in 4 months, the fate of Cornwallis' efforts were left to subordinates who failed miserably to deliver. Morgan, in an action equal to the actual battlefield victory at Cowpens, managed to extricate himself from getting crushed by Cornwallis' main army.

The latter was operating with poor intelligence as to Morgan's exact location and did not leave his camp to chase the Americans until two days after the battle, 19 January. Even then, by the 25th, he was held up at Ransour's Mill in North Carolina by flooded rivers while Morgan was easily two day ahead of him.

Frustration

One can almost sense the frustration in Cornwallis by now. His campaign into NC and then on into VA was set back almost 6 months by impetuous subordinates and by the end of January, it seemed like the British would never get moving. The British general apparently decided to make the army more mobile by burning most of the baggage, starting with his own. He intended to chase Greene down if it was the last thing he did. If not frustration with events, why else would this methodical, excellent commander commit himself on a course that had the potential for disaster?

I do not intend to discuss the specifics of each small skirmish during the North Carolina campaign of the spring of 1781. From the time Cornwallis began to march north in earnest on 29 January and the battle of Guilford Court House on 15 March, portions of the opposing amnies skirmished at Cowan's Ford, Tarrant's Tavern, and at the Haw River in North Carolina. Tarleton and the British Legion dragoons (most of whom survived Cowpens while the Legion foot was almost totally killed or captured) figured prominently in the first two, Lee's Legion (recalled temporarily from partisan operations with Marion) in the third.

Greene's plan was to continually fall back from Cornwallis' advance and then turn on the British when their lines of supply were effectively cut. Greene basically dangled his little army as bait being the carrot on the stick in front of Cornwallis. The famous "Race to the Dan" was on, Greene trying to cross that river into Virginia, Cornwallis trying to catch him and annihilate the American army.

The weather was rotten, altemating between rain and snow. The rivers were almost impossible to cross without boats. Here Greene had the upper hand, being able to confiscate boats as he crossed which delayed Cornwallis further. By 13 February, part of Greene's rear guard, Lee's Legion, was engaging in sharp encounters with Cornwallis' advance force of Tarleton's British Legion.

The rest under Col. Otho Williams was in danger of being overtaken by Cornwallis who was force-marching his army. By the end of the 14th, the British had marched 40 miles in 24 hours while the Americans had covered the same ground in only 16. Less than an hour after the last of William's forces crossed the Dan, British General O'Hara with part of the Guards Battalion showed up at the fords to find them uncrossible and the boats on the other side.

Northward

Cornwallis did not drive north. By February 1781, additional American forces were in Virginia and combined with Greene's would have outnumbered the British army. The general decided to fall back to the relatively friendly confines of Hillsboro to resupply and regroup.

On 18 February, only four days after winning the race to the Dan, Greene ordered part of his army south again to harass British lines of communications, reinforce militia operating under Andrew Pickens, and basically bully the local Tory population. Greene recrossed the Dan with the bulk of his army on the 23rd. Greene spent the next week moving his army back and forth while his two independent groups under Pickens and Otho Williams continued to snipe at the British flanks.

Cornwallis left Hillsboro on the 27th and again, was becoming annoyed with American activity. His supplies were becoming critically short and unless he fell back into eastern North Carolina he needed to bring Greene to the battlefield. Retreating would effectively abandon the Tory cause in most of the state.

In the week prior to Guilford Court House, Greene finally received significant reinforcements, in the form of Continentals dispached from Virginia and militia call ups. The militia by this time was a tad better than what is normally envisioned of this much maligned group. Many Virginia militia units in fact consisted of ex-Continentals having mustered out of the "regular" army. These units, if given concise orders and not relied upon too much were effective on the battlefield.

Guilford Court House

Greene chose his battlefield at Guilford Court House and Cornwallis was more than willing to meet the challenge . Actually, the British general's intelligence suggested that his force of about 2,500 troops was outnumbered 4:1. In fact, he was only outnumbered about 2:1 and in any case, was undeterred.

Cornwallis won a pyrrhic victory at Guilford. Yes, he beat an army in a prepared position being significantly outnumbered but the cost was too great for the outcome. He still had to fall back to the Carolina coast, this time to Wilmington. After almost three weeks rest, he decided to march into Virginia, hoping to both entice Greene after him and to link up with the sizable British forces now operating in that state.

We leave poor general Cornwallis for the time being to follow the renewed campaigning in South Carolina. Greene decided to ignore Cornwallis' move north, instead striking at the British outposts and garrisons in that state. He sent Lee to hook up with Marion again who was doing his usual outstanding job harassing the British lines of communications. The two succesfully took Fort Watson on 23 April.

More AWI Southern Campaign

-

Part I: Origins to Battle of Camden

Part I: Post Camden to Battle of Guilford Courthouse

Part II: Post Guilford to the End

OOB: American and British Forces in the Campaign

Campaign Rules for American Revolutionary War

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #66

Back to Courier List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com