A review of really old issues of the Courier show a wealth of well done articles by people like Steve Haller on the American War of Independance (AWI). But what has happened in the last 20

years? True, the Seven Years War has become popular, either as a linear event set in Europe or skirmish game occuring in North America. The good old AWI seems left out, both in rules and

activity.

A review of really old issues of the Courier show a wealth of well done articles by people like Steve Haller on the American War of Independance (AWI). But what has happened in the last 20

years? True, the Seven Years War has become popular, either as a linear event set in Europe or skirmish game occuring in North America. The good old AWI seems left out, both in rules and

activity.

When "Gorges & Sash" was being published in the 1980s, you would usually find at least one article per issue on some neat, eclectic portion of the AWI. Unfortunately, that publication is no longer produced leaving a void of sorts in the period. Fortunately, figures have not dropped out of the market

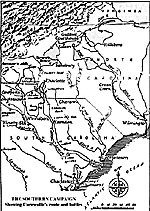

This article will, hopefully, be one of several on one aspect of the AWI, the Southern Campaign, starting in late 1779 and running to Yorktown in October 1781. I have always preferred this portion of the AWI over the probably more well known Northern theater because of the battle styles, troops, and personalities involved. In later articles I hope to provide some analysis of the battles and the leaders. Also, I will give a complete order of battle, and uniform guides. Just think of this as a "theme" series without the formality.

With the exception of the battle of Camden and the siege at Yorktown, army sizes were small. Movement was swift, guerilla warfare was extremely important, cavalry operations took on greater emphasis, and the battles themselves offer many options for the gamer. The Southern theater is easy to campaign as well as play out different aspects of warfare in the period. Standard linear battles (like Camden), sieges (as at Fort 96), and skirmishing (pick just about any militia encounter, cavalry operation, or anything Francis Marion did? all had equal play.

Also, unlike the Northern Theater, American troops, if commanded effectively, apparently did not have to play catch up with their British counterparts in fighting stand-up battles. Quite frankly, the American forces up until 1778, with few exceptions, were not very adept at fighting linearly. When the Southern Campaign gets underway, there was a core of leaders and soldiers quite capable of standing toe-to-toe with the best troops of the British Empire.

The character of the war and its participants was also dramatically different. The Southern Campaign was more of a civil war, not one against the "tyranny" of a seemingly foreign power. Neighbor fought neighbor and certain aspects of the guerilla war and British occupation have eerie parallels in modern insurgency movements.

Many of the battles involved no British or German soldiers, just American vs American. Furthermore, with the exception of some of the minor skirmishes among opposing militias most of the Tory forces actually came from the New York and New Jersey area.

The people who stand out in this period are many and often are misunderstood. Banastre "Bloody" Tarleton and Lord Cornwallis are the best known of the British. The former, while being bold, his performance on the battlefield was mixed and was resented his British counterparts. The latter is seen by most Americans as a loser based on the Yorktown siege. Yet he went on to campaign successfully in India and inspired extreme loyalty in his troops.

The American leaders are many and colorful. Daniel Morgan, a middle-aged frontiersman with a very bad case of hemmorroids, fought perhaps the best battle by American forces during the war at Cowpens. Nathaniel Greene never actually won a battle yet won the war. Some of the militia leaders, like Francis "The Swamp Fox" Marion and Thomas "Gamecock" Sumter were more than qualified to lead regular forces also. "Light Horse" Harry Lee father of the more famous Civil War general was another bold figure who emphasized combined arms and speed in his legion of troops.

All in all, a fascinating part of the AWI and one that might need a hit of attention or re-attention as was my case.

BACKGROUND

The "southern campaign" actually had its roots in 1776 when the British attempted to take Charleston. Overly cautious plans of attack by the land commander Sir Henry Clinton and the naval commander Sir Peter Parker plus friction between the two, eliminated any success of taking the town.

The "southern campaign" actually had its roots in 1776 when the British attempted to take Charleston. Overly cautious plans of attack by the land commander Sir Henry Clinton and the naval commander Sir Peter Parker plus friction between the two, eliminated any success of taking the town.

Large version of Map (slow download: 102K)

The second military operation prior to the real southern campaign was the British capture of Savannah in late December 1778. The resulting joint Franco-American siege and assault was a fiasco leaving bitterness on both sides of the alliance. Admiral d'Estaing's sailed away after a failed assault and the British had secured their first foothold in the south.

CLINTON'S GRAND STRATEGY

After almost four years of fighting in the northern colonies, the war in the north was stalemated and the British could hear the clock ticking. How long could Britain fight a war against both the rebels and France was in question especially with the growing negative public opinion about the war in England. The other factor (one that guided much British strategic thought as it affected operations in the colonies) was the Loyalists. The British perceived, quite rightly for a change, that Loyalist sympathies away from New England and the Middle colonies were strong. However, the difference between sympathizing and taking up arms was considerable.

The British army could only guarentee security to the faithful in America if it actually garrisoned a location. Once the army left, the Loyalists were left to the mercy of the local patriots. At best, renewed guerilla warfare broke out between competing militias similar to what has been faced today with insurgency movements. This was prohably the biggest factor in keeping the Loyalists from flocking to the British flag.

All this being said there were some sound strategic considerations in a move south. When Sir Henry Clinton took over command of Britain's North American operations in early 1778 he consolidated his position in the north mainly by abandoning Philadelphia. With French entry into the war he reasoned that the north could be effectively blockaded by the navy leaving enough ground forces to operate south. By securing the area from Georgia up into Virginia. Clinton reasoned that the main forces and rebellion in the north could not continue.

THE CAMPAIGN BEGINS

In December 1779. Sir Henry sailed south with about 8,500 men. But a terrible storm necessitated regrouping in friendly Savannah before setting off for Charleston, the main target in Clinton's grand strategic plan.

Unlike in 1776 when the British made every possible mistake Clinton conducted the siege of Charleston in an almost businesslike manner. On 11 February 1780 he landed the army about 30 miles south of the city and had the navy blockade the port without attempting to run the foes. He methodically moved his forces northward coming at Charleston from the southwest.

Charleston lays at the end of a narrow peninsula with the Ashley and Cooper rivers on either side. Taking the "neck" of the penensula would cut off any hope of retreat except by sea an impossibility for the Americans even if the British fleet was not hovering nearby. Clinton aimed at crossing the Ashley and establishing positions on the neck. Advance elements made the crossing on 20 March the rest of the army nine days later. No opposition was encountered during any of Clinton's operations.

On 1 April the first of the siege lines was begun. A week later the British fleet under Admiral Arbuthnot easily ran the forts Moultrie and Johnson which defended the harbor. He could not however move up the Cooper river since the American flotilla had been sunk at its mouth in order to prevent British passage. The route over the Cooper could have been used to escape had the Americans chose to do so until the 28th, by which time Cornwallis second in command had moved down the eastern bank of the Cooper sealing off any avenue of escape. On 12 May the Continental commander Major General Benjamin Lincoln surrendered in probably the greatest defeat since the loss of New York.

What were the Americans doing all this time? General Lincoln never seemed to seize upon the vulnerabilities of his position in town and in fact and taking his lead from governor John Rutledge insisted on defending it to the bitter end. That approach meant that reinforcements kept arriving. most notably veteran North Carolina and Virginian Continental troops which showed up in early April only to go into the bag.

The defeat at Charleston was costly especially in terms of men and material. To make matters worse a small force of Virginia Continentals which arrived too late to get caught in the siege was retreating north when it received news of Charleston's fall. Banastre Tarleton and the British Legion overtook the force, killing or badly wounding over 250 troops, many after trying to surrender. Unfortunately for the British, this "massacre", which in fact was no worse then some other incidents that would subsequently occur during the Southern Campaign, would become a rallying cry for the American cause.

Tarleton's Quarter

The term "Tarleton's Quarter" helped galvanize anti-British sentiment better than any Patriot propaganda pamphlet. It also characterized the vicious nature and civil war within a civil war nature of the Southern Campaign.

The civil war nature of the Southern Campaign is well illustrated by four skirmishes that took place between the fall of Charleston on 12 May and the battle of Camden on 16 August. The first occurred at Ramsour's Mill on 20 June in North Carolina and consisted of 400 Patriots fighting 700 Loyalists, all militia.

The second occurred on 12 July at Williamson's Plantation in South Carolina where a force of' 250 Patriots surpised and routed a Tory raiding party. The third introduces General Thomas Sumter, a general in the South Carolina militia, he attacked a Loyalist outpost at Rocky Mount, South Carolina on 30 July. This time, a detachment of a "formed" Loyalist unit, the New York Volunteers, augmented the local milita and beat off Sumter's attacks.

Not to be deterred, Sumpter decided to move against another heavily defended outpost at Hanging Rock, 12 miles east of Rocky Mount. Garrisoned by regular Loyalist regiments, including part of the foot of the British Legion, the target was not easy to take with even Sumter's better than average militia. After wandering around in the dark. all three of Sumter's columns inadvertently descended on the British left, overwhelming it in short order. The center collapsed shortly thereafter.

The routing Loyalist units fell back to where the still steady British Legion foot stood and. in something rarely seen during the American Revolution, they formed hollow squares. Unfortunately for Sumter, his men fell to looting the camp and he was never able to reorder the situation. Faced with the now steady Loyalists in square, he withdrew.

These four "battles" had no British or Continental troops involved although the Loyalist regiments at Hanging Rock were as good as most standard line units of the day. They do show the growing reliance on local commanciers like Sumter taking initiative against their nominal neighbors. Likewise, the regular Loyalist units, most of whom actually came from New York or New Jersey who augmented the local Tory militia added to the "American only" flavor of much of the Southern Campaign.

The subsequent battle of Camden probably set back American fortunes in the South more than the loss of Charleston. Sir Henry Clinton left for New York in June, hastened by the news that the French troops were enroute from France. In April, Washington had dispatched about 1,400 Continentals and artillery under Baron de Kalb. The Baron waited around in North Carolina after hearing about the loss of Charleston. It was hoped that the presence of some regular forces would whip up local militia support but little happened.

Meanwhile, Congress had appointed Gates in charge who, over de Kalb's objections, immediately ordered the ill-provisioned army to march straight to Camden over a route through barren country with a generally hostile population. It was in a sorry state when it met the British advance guard under Francis Lord Rawdon on 11 August.

Gates dispatched 100 of his best troops, Maryland Continentals, to help Sumter chase down a British supply train. Ignoring de Kalb's recommendations regarding the approach to the British advance party, refusing to take advantage of the partisan groups (including Francis Marion, the "Swamp Fox") which joined and offered to scout, Gates decided on a night march on the 15th, (after a 3 week approach march with diarrhea rampant in the ranks ). The American army was probably in worse shape at the start of the battle than it was five days prior when it arrived in the area.

Gates did not even have an accurate feel for the number of effectives he could field. Both he and Cornwallis, who had taken over British command in the South, estimated the American army to number about 7,000. Cornwallis knew precisely how many men he had, 2,200. Cornwallis showed for the first time, as he would do time and time again later, the supreme confidence he had in his forces.

The fact that he had portions of two elite regiments, the 23rd Fusiliers, and 71st Highlanders, plus the British Legion, two line regiments and several regular Loyalist units, made it easy to trust in his soldiers. Gates, on the other hand, actually had about only 3.000 troops ready (as they were) to fight. Of these, only about 1,000 were good - being mainly Delaware and Maryland Continentals plus some Virginia state troops. The rest were militia.

Smashing British Victory

The battle was a smashing British victory. The Virginia militia on the left, in the face of a British bayonet charge, routed en masse through the Maryland Continentals. Gates, having no clue as to what was happening, left with the militia. All that remained was the American right flank headed by de Kalb. It fought superbly and for two hours repeatedly drove off the British. The end came when de Kalb was mortally wounded and Tarleton with the British Legion cavalry decended on their rear.

The American loss was complete. Virtually all of its Continental troops were dead or captured, all its artillery gone, and worse, one of its best generals killed. Gates, however, made the 180 mile trek to Hillsboro, North Carolina, in just 3 days, not bad for an overweight man of 52.

Modern historians feel that from the British perspective, Camden alone more than made up for the loss at Saratoga. I feel that Charleston and Camden together would be as significant as Saratoga, however it did not alter the world political dynamics.

More AWI Southern Campaign

-

Part I: Origins to Battle of Camden

Part I: Post Camden to Battle of Guilford Courthouse

Part II: Post Guilford to the End

OOB: American and British Forces in the Campaign

Campaign Rules for American Revolutionary War

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #66

Back to Courier List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com