Japanese invasion plans called for an assault on the north/northwest coast of the island, near the vicinity of Devil's Peak. All three regiments of the 38th Division were to take part, each regiment

committing two battalions.

Japanese invasion plans called for an assault on the north/northwest coast of the island, near the vicinity of Devil's Peak. All three regiments of the 38th Division were to take part, each regiment

committing two battalions.

The Japanese coming ashore from barges in late 1941, perhaps at Hong Kong (Hutchinson's Pictorial History of the War)

To prepare for the invasion the Japanese made several sea borne sorties to test the island's defenses; search lights and artillery posts being the object of their attention. The invasion was to be preceded by aerial and naval bombardment throughout the island.

The main focus of the assault was to be the north-east quarter of the island. Primary objectives included Mount Nicholson, Mount Butler, Mount Parker, Jardine's Lookout, and the critically important Wong Nei Chong Cap.

Once secured, they were to move on to the surrounding areas near Mount Nicholson and control Repulse Bay. Forming the western edge of the invasion forces was Shoji's 230th Regiment. Occupying the center was Doi's 228th Regiment, and to the east of him, Tanaka's 229th Regiment. All regiments were to land two battalions each.

Of all the objectives, the gap was considered the most important. Securing it would sever the East and West Brigades. Occupying the Gap was the West Brigade HQ of Brigadier Lawson. With him were three platoons of Winnipeg Grenadiers - his motorized reserve. In the late hours of 19 December, they awaited the inevitable invasion.

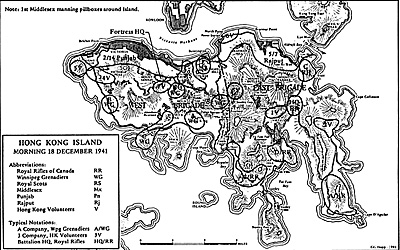

Jumbo Map of Hong Kong's British Positions (slow: 184K)

The evening of the seaborne assault was overcast, raining, and quite miserable for all troops deployed. For that reason, an invasion was considered to be unlikely. The Japanese decided to invade that particular night for that very reason. The ill weather helped to shield their assault craft. On the evening of the 18th, the Rajputs were forced to endure the entire weight of this invasion force. They didn't have a chance.

Up to this point, the Rajputs had been forced to dig in and survive with almost continuous air and naval bombardment. Many of their pillboxes and all of their search lights had been destroyed. What's more, the Rajputs were expected to maintain a three-mile front with 700 men. These soldiers were stressed and ready to crack. Under the cover of darkness, the Japanese attacked. Despite isolated moments of stiff resistance, the shell-shocked Rajputs broke.

By the early morning of the 19th the Rajputs, save the most westerly company, ceased to exist as the remnants scattered to rearward positions.

Rapid Headway

Bypassing any strong points, the Japanese made rapid headway. As planned, their main body of troops landed between North Point and Braemar Point. Once ashore, a considerable number were ordered towards the Gap. The Gap itself would soon be under assault by four battalions split evenly between Colonel Shoji and Colonel Doi. However, all of this was yet to come; for the moment, the only confirmation of their whereabouts came from fleeing Rajputs and volunteer forces.

Unfortunately, those reports were not considered reliable. At these critical hours, the British High Command from General Maltby down to his respective Brigadier Generals, was completely unaware of the actual events. By the time a decision was made to react, the Japanese were ashore in strength. The chances of pushing the Japanese back to the sea, or even containing them, had now passed.

Once word reached Lawson of the fleeing Rajputs, he immediately ordered two of his motorized platoons to proceed northward to counter the Japanese threat. But what became of his platoons? One of them managed to reach the high ground between Wong Nei Chong Cap and the beachhead at Jardine's Lookout. Here it encountered superior enemy forces and was forced off the hill. In addition, its commander was killed in action. The other platoon tried to reach Mount Parker, northeast of Jardine's Lookout, but once there found strong Japanese forces on the summit.

To make matters worse their commanding officer was also lost in combat. Realizing his deteriorating situation, Lawson ordered "A" company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers into action. Led by Sergeant-Major Osborn, they were to proceed towards Jardine's Lookout and Mount Butler. Much to his chagrin, Osborn's troops became separated in the darkness.

Gathering his remnants, Sergeant-Major Osborn located Mount Butler and proceed towards it. Finding Japanese troops already there, Osborn led a bayonet charge on the summit and by sheer surprise and tenacity occupied it. Later accounts recalled that Osborn literally grabbed, kicked, pushed, and lifted his less than enthusiastic men up the summit. To the credit of Sergeant-Major Osborn, sheer determination turned a company of reluctant men into a unified unit willing and able to combat enemy troops. Over the next hours these men would do even more than expected, few would come back from it alive. For the time being they had the summit and relished it.

Colonel Doi reacted quickly and ordered a counterattack. This attack cleared the summit and put Sergeant-Major Osborn in a compromising position. Despite regaining contact with the rest of his company his forces were outnumbered and surrounded. Beating off repeated assaults, Sergeant-Major Osborn rose to the occasion and became a pinnacle of strength to his men. Time after time -always screaming obscenities - Osborn hurled back incoming grenades and beat off the assaults in brutal hand-to-hand combat.

Eventually, and despite all the defender's heroism, the Japanese superiority in numbers proved too great. After eight hours of continuous combat Osborn's company was reduced to less than a dozen men. In a last act of heroism Sergeant-Major Osborn, a veteran of World War One and now at the age of fortytwo, gave up his life to save his men.

With grenades inundating their positions, Osborn made a final desperate bid for survival. In whirlwind fashion he repeatedly hurled back grenade after grenade into the closing enemy. There was one too many; realizing this he hurled himself on the grenade and took the brunt of the explosion to save the lives of his men. When the fighting was over the Japanese spared the lives of the defeated and paid tribute to the fallen men. In recognition of his unparalleled heroism, Sergeant-Major Osborn was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

Meanwhile, misfortune continued to plague Brigadier Lawson. A reinforcing contingent of three naval platoons and "A" Company of the Royal Scots never made it to their assigned positions. In both cases they were either ambushed or beaten back with heavy losses. It was not surprising since their reliance on roads made them easy targets and cost them dearly. Realizing the perilous position of his HQ, Lawson ordered a relocation.

The decision came too late. Before his order could be carried out, Wong Nei Chong Gap was overtaken by Colonel Shoji's forces. In the subsequent firefight, Lawson became another fatality. By 10:00 am 19 December the Gap fell under Japanese control. Most importantiy, the West Brigade was without a commander. For the next precious hours, coordinated decisions would not be forthcoming. Meanwhile back at the main HQ, General Maltby remained oblivious to the actual events. As far as he could determine the Japanese had not yet committed all their troops, and he was hesitant to commit his.

Elsewhere on the island, the heavy fighting continued. At the north coast at the western edge of Japanese penetration was located the Power Station. Here another struggle unfolded. Assigned to the sedentary role of preventing sabotage to the Power Station was a company of elderly volunteers, "The Hughesiliers". The force consisted of distinguished businessmen all over fifty years of age. Some were World War One veterans including 'Top Hingston" who was in his seventies. Supplementing them were two platoons of Electric Company volunteers.

Almost immediately, the Hughesiliers found themselves in the thick of fighting with Colonel Shoji's forces. In an effort to relieve them, a Middlesex machine gun platoon led by an armored car was dispatched. The armored car never made it. After having it knocked out the Middlesex continued on, only to have all three of their trucks destroyed. Determined, they proceeded on foot and finally reached the beleaguered Hughesiliers.

Encircled now, this motley crew dug in for the fight. The struggle lasted eighteen hours. With their ammunition supplies depleted and their men exhausted, they surrendered. Although defeated, they had bought enough time to allow the rest of the island defenders to form new defensive positions just west of Leighton Hill.

By now General Maltby was acutely aware of the Japanese invasion. He ordered an immediate counterattack by all available forces towards the Gap. The forces participating in this effort were three companies of Royal Scots, and a mixed Grenadier detachment. On the northern flank, the Royal Scots attempted a two-pronged attack but were repulsed with heavy losses. Captain Pikerton of "Golden Hill" fame became wounded and all other company commanders also became casualties.

Further south, the Grenadiers actually got through but were too weak to contest the area and withdrew to their former positions. Unfortunately, the Grenadiers suffered most of their casualties during the retreat. By the evening of 19 December the West Brigade's losses included 66% casualties in the Royal Scots; "A", "D" and HQ Companies of the Grenadiers effectively disabled, and Brigadier Lawson dead.

During this particularly difficult time, the East Brigade was unable to provide assistance. They too were caught in a whirlwind. Brigadier Wallis was organizing efforts to contain the Japanese spearheads, but without aerial reconnaissance he could not determine the location or strength of the Japanese assault forces. Landing on his eastern sector was Colonel Tanaka's 229 Regiment. Tanaka's troops swiftly gained the heights of Mount Parker, captured the fort at Sai Wan Hill and overran the 5th Volunteer Battery. In the vicinity was a major at OP, who, upon encountering fleeing volunteers, determined to retake Sai Wan. Of first priority was obtaining artillery support. Incredibly, his requests were denied.

The reason? Fortress HQ could not believe that the fort had fallen into enemy hands. In disbelief, Bishop vehemently insisted that the Volunteers had been ousted from the position. Ultimately Brigadier Wallis, fed up with Major Bishop's "insolence", cancelled all artillery support requests. With enemy gun fire blazing his position - many of which were undoubtedly captured Lewis guns from Sai Wan - Bishop let off a last departing shot at HQ. Regarding the current occupants of Sai Wan he exclaimed, "they sure as blazes aren't acting in a friendly manner." And so ended another futile attempt by the British garrison to regain some form of initiative. As we shall see, this type of confusion plagued the British throughout their ill-fated campaign.

Prime Minister to Governor, Hong Kong

21 Dec. 41

We were greatly concerned to hear of the landings on Hong Kong Island which have been effected by the Japanese. We cannot judge from here the conditions which rendered these landings possible or prevented effective counter-attacks upon the intruders. There must however be no thought of surrender. Every part of the island must be fought and the enemy resisted with the utmost stubbornness.

The enemy should be compelled to expend the utmost life and equipment. There must be vigorous fighting in the inner defences, and, if the need be, from house to house. Every day that you are able to maintain your resistance you help the Allied cause all over the world, and by a prolonged resistance you and your men can win the lasting honour which we are sure will be your due.

New British Positions

Having lost Sai Wan, Bishop's "C" Company made a great show for itself at new positions centered east of Mount Parker. Here they stopped Colonel Tanaka's 2nd Battalion from advancing further and caused it over 65% casualties. Elated by this success, "C" Company awaited their next challenge. It was not to come. Much to his chagrin, Bishop had to order his disheartened troops to pull back. They were in danger of being outflanked by Tanaka's 2nd Battalion which had already bypassed the western slope of Mount Parker.

Now fully aware of the Japanese intrusions, Brigadier Wallis ordered a withdrawal for almost his entire Brigade to new positions around Stanley. Here he hoped to regroup and counterattack in strength. Unbelievably, misadventures haunted the British forces yet again. Due to the death of a commanding officer, a subordinate misinterpreted his orders and deliberately destroyed his howitzer battery! This poor chap received orders that stated

British machinegun nests in the hills of Hong Kong (Hutchinson's Pictorial History of the War) that his battery was to "get out of action."

He did an admirable job. As a result of this ambiguity, the only mobile artillery left to the East Brigade were two 3.7 howitzers and one 18 pounder. Compounding the situation was the withdrawal itself: fleeing Rajput and Volunteer detachments intermingled with Royal Rifles and cost the Brigade additional time to reorganize.

As a result of the fall of Wong Nei Chong Gap and Wallis' withdrawal order, the East and West Brigades effectively fought as two separate commands for the rest w',he campaign. Over the next two days various attempts were made to regain contact and retake the Gap. Of note, the West Brigade's efforts were marred by uncoordinated piecemeal attacks.

On 20 December another two-pronged assault towards Mount Nicholson, by the very depleted Royal Scots and "B" Company of the Grenadiers, was approved. In actuality, the Royal Scots moved hesitantly and assumed defensive positions almost immediately! Meanwhile, and unaware of the Royal Scots decision, the Grenadiers moved out.

They split into two columns and moved directly into the path of Colonel Doi's battalions. Amidst the fog and rain, Doi managed to push back the Grenadiers and capture the heights of Mount Nicholson. Once there, the Japanese beat off numerous determined attempts by the Grenadiers to attain their positions. Charging up the slopes of the mountain, the Grenadiers gave Colonel Doi's troops a vicious battle.

Doi reported that he was attacked by over 400 men - in fact only 98 - and his troops low in ammunition had to resort to hand-to-hand combat and throwing rocks from the summit. Casualties on both sides were heavy, but by the end of the day the Grenadiers gave up and assumed new defensive positions further west at Mount Cameron. Thus ended the West Brigade's last serous attempt to recapture the Gap. By failing to control Mount Nicholson, the British gave the Japanese a free hand to transfer troops in and out of combat.

With the fall of Mount Nicholson, the situation of West Brigade appeared bleak. In the north at Leighton Hill a Middlesex company was holding out against Shoji's forces. South of them near Mount Cameron were the Royal ',cots and remnants of the Rajput battalion. Further south were the recently mauled Grenadiers, reinforced by volunteer, naval and Middlesex detachments. Adding to the turmoil were the continuous pleas of British officers to fight in the front lines. Many of them, undoubtedly inspired by Captain Pikerton, became irreplaceable losses. This steady loss of officers resulted in continuous breakdown of HQ directives.

Elsewhere, the Hong Kong Naval detachments ceased to exist. After attempting to stifle the flow of Japanese reinforcements, most of their ships, including MBTs and aged warships, were either grounded, sunk, or destroyed. For the duration of the campaign the British Navy was no more than a nuisance to the Japanese main efforts. In addition, it must be remembered that the British units had to endure continuous naval and aerial bombardment. Further, the captured British munitions and artillery pieces were put to good use by the Japanese. The British coastal guns were hampered by their arc of movement; most could not turn their guns to fire landward. Of those that could, little was achieved since most of their ammunition was of the armor piercing kind and totally unsuitable for infantry assaults.

The Japanese had the luxury of ferrying in fresh troops and could rely on their numerous artillery pieces. Finally, the critical weakness of the British position was revealed: the Japanese had by now effectively cut off the main water supplies to the West Brigade. Clearly then, it was not a matter of victory or defeat, but of how long the British forces could hold out and tie up the Japanese.

Surprisingly, a bright spot that still existed for the defenders were the still isolated and cut-off units to the rear of the Japanese front lines. It was these isolated pockets that consumed a lot of the Japanese attention and deflected the full fury of their assaults. Of interest, "D" Company of the Grenadiers cut off near the Cap fought on valiantly until 23 December, all the meanwhile harassing any and all passing Japanese troops movements.

These gallant men only surrendered when they had exhausted their ammunition and when the Japanese brought in a tank to blow away the steel shutters of their shelters. Elsewhere, at Little Hong Kong a company of Middlesex held out until the final capitulation of December 25.

After refusing another offer to surrender, the British dug in and prepared for further assaults. In response, the Japanese began continuous aerial bombardment of all front line positions. The Middlesex at Leighton Hill were outflanked and forced back to Mount Parish. Augmented by what was left of the Rajput and the now arriving Punjabis, the Middlesex formed their last line of defense.

South of them, Mount Cameron fell after 230 desperate Grenadiers and engineers tried in vain to hold off a reinforced Japanese battalion. Once in enemy hands, the summit of Mount Cameron became the target of British 9.2" coastal guns.

Predictably, their armor piercing shells had little effect. Just south of Mount Cameron, the British forces there were forced back to escape the danger of a Japanese flanking assault. They formed new lines just east of Aberdeen at Bennet's Hill. Curiously, "C" Company of Grenadiers kept marching westward and did not stop until it reached Pok Fu Lam, a full three miles west of the front line. Its commander had set it upon himself to march his unit around the periphery of the island and set up new positions at Mount Gough! Once aware of this unauthorized action, General Maltby, fuming in disgust, ordered the unit back to Aberdeen.

And while the British struggled with uncoordinated moves the Japanese readied themselves for the final push. On Christmas Day one last offer of surrender was presented by General Sano, and was again rejected by General Maltby. At this point in time a telegram from Churchill was circulated amongst the troops (see accompanying sidebar).

Buoyed by Churchill's message and ceaseless rumors of a Chinese relief force, the British troops indulged in a Christmas dinner and wrestled with their coming fate. For many of the soldiers, that Christmas dinner made up of extra rations was to be their last feast until the war's end. Almost predictably, the last hours of resistance by the West Brigade ended in futility. At noon the Japanese assault began. Within hours the defensive positions collapsed. Finally, and mercifully, General Maltby decided that further resistance was meaningless and ordered a general surrender.

Unaware of the capitulation of the West Brigade, the East Brigade commanded by Brigadier Wallis continued its resistance. Ever since the two brigades were separated, efforts were continuously made to recapture the Gap and at the very least relieve the isolated civilian enclave near the Repulse Bay Hotel. Assigned to this role was the Royal Rifles. Unfortunately, what should have been a fast and desperate reaction turned into a series of confused, countermanded, orders. Certain units marched back and forth and accomplished nothing.

Nevertheless, a type of an assault got under way spearheaded by "A" Company. The promised artillery support never materialized as the guns were still in transit at the time of the attack. Not surprisingly, the attack was a failure. The company did not renew its attacks; it couldn't. Major Temples discovered that all of his Bren guns were jammed. Ironically, their failure probably saved a great many lives. For if the attack had succeeded, the unfortunate company would have been immediately in the path of two of Doi's battalions, now entrenched and supported by light tanks and various howitzers!

This dismal uncoordinated assault proved to be the last effort of East Brigade to regain the Gap. From here on, the East Brigade had to fight for its sheer survival. Brigadier Wallis, now in danger of having his own forces split in half, ordered another retreat. This time a full retreat to Stanley Peninsula. Colonel Tanaka did not waste time. Fresh troops were committed immediately upon arrival to his southwardly thrust. He had four battalions to confront the exhausted Royal Rifles and their accompanying units.

At 12 noon, 22 December, Tanaka attacked. In positions centered around Sugar Loaf Hill, the Royal Rifles stiffened their resolve and exchanged shots with the attackers. In the following hours Sugar Loaf Hill exchanged hands several times. Eventually, the Japanese endured and proceeded on. Subsequent to their breakout, the Royal Rifles abandoned Stanley Mound and began another one of those endless retreats. This time it was towards Stanley View. They knew it couldn't last much longer: they were soon to run out of land.

By 23 December the Royal Rifles were down to 350 effective fighting men. Haplessly, this last withdrawal managed to separate a contingent of troops in the adjacent Chung Hum Kok Peninsula. These men were to remain cut off for the rest of the campaign.

Temporarily relieved by Middlesex and volunteer units, the bruised Rifles entered Stanley for a brief respite. The Middlesex made a good show of themselves and beat off numerous Japanese intrusions into Stanley Village. However, they eventually succumbed to superior numbers and fell back.

At this point Wallis ordered the Rifles to assign their best able company to recapture the lost position. Promised artillery support, "D" Company prepared for their assault. At 1:00 pm, 25 December, the attack signal was given. Immediately, a pointless military endeavor turned into a senseless tragedy. Attacking in broad daylight and leaving their entrenched positions, "D" Company advanced. The attack required them to attack uphill in exposed positions against well established Japanese forces. The fact that they attacked with inferior numbers only added to the calamity. Ominously, and despite very heavy casualties the Rifles surprised the Japanese, reached the summit and engaged them in hand-to-hand combat.

In short order Tanaka's forces beat back this spirited "attack." When it was all over "D" Company failed to exist. Of the 148 men committed to the effort 104 became casualties. It was a disaster. The promised artillery support never came through. Either the coastal guns could not reach the targets or incredibly, the assigned artillery did not reach positions in time for the assault. What's more, and even beyond comprehension, one artillery unit failed to move 100 yards in the six hours allotted to their assignment! How Brigadier Wallis failed to confirm the readiness of his troops is unknown. Incredibly, when word got to Wallis of the unsuccessful attack, he immediately ordered another company into action! "A" Company took the assignment and just as quick suffered 18 casualties. Mercifully, before the attack got completely underway it was halted. News had finally reached Wallis of Maltby's surrender. The campaign was over.

The Fall of Hong Kong 1941

- Introduction

Japanese Attack: Dec. 8

The Assault on the Island

Final Assessment

Jumbo Map of Attack on Hong Kong (slow: 187K)

Back to Table of Contents: CounterAttack # 4

To CounterAttack List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by Pacific Rim Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com