Hong Kong seemed far removed from the war that engulfed Europe

in the fall of 1941. Russia was on the brink of collapse while the Japanese Empire looked on.

Hong Kong seemed far removed from the war that engulfed Europe

in the fall of 1941. Russia was on the brink of collapse while the Japanese Empire looked on.

Photo: Japanese bombs falling on the Hong Kong mainland (Hutchinson's Pictorial History of the War)

To the British colonists gambling freely at the Hong Kong casinos, an attack on their colony seemed unthinkable. Surely, they thought, the Japanese would place their interests elsewhere. However, despite advice to the contrary, the British High Command mobilized the colony, brought in reinforcements, and reassured the colony of its continued support.

The Japanese were given a clear message - Hong Kong would not fall without a fight. Unfortunately, the British underestimated the Japanese threat, and overrated their own capabilities. The unthinkable was about to occur ... the Japanese were not deterred. As a result, this British colony, which was expected to fight for at least six months, fell in less than three weeks of combat. This unexpected debacle witnessed unorganized, confused resistance and featured a terrible, futile tragedy reminiscent of the famed Light Brigade at Balaclava.

In the fall of 1941, the British garrison of Hong Kong consisted

of 5400 regular infantry and 600 other miscellaneous troops organized

into six battalions and auxiliary units.

In the fall of 1941, the British garrison of Hong Kong consisted

of 5400 regular infantry and 600 other miscellaneous troops organized

into six battalions and auxiliary units.

Anti-tank gun of the ill-prepared British at Hong Kong (Hutchinson's Pictorial History of the War)

The six battalions were made up of the 2nd Royal Scots, the 1st Middlesex, the 2/14 Puniabis, the 5/7 Rajputs, the Montreal Royal Rifles and the Winnipeg Grenadiers; the last two units of Canadian origin. None of these units was considered battle ready. A lot of them had lost key personnel to active units in other theaters of the war.

Of note, the Canadian battalions were deemed to be "C" formations: insufficiently trained, and unfit for operational duties. Indeed a sizeable percentage of these men had not received adequate training in the firing of their own rifles and/or Bren machine guns! Further, these units, although designated as motorized, arrived in Hong Kong without their motor transport and were relegated to the role of foot infantry throughout the campaign.

Realistically, these forces were not expected to hold out for any long period of time. They were there to give the Japanese government a political message: the British were prepared to fight for their colonies.

The arrival of the Canadian battalions was intended to reinforce that message. In addition, these forces were to reassure the Chinese that the Allies were not about to abandon Hong Kong. Unfortunately, even the British High Command was divided on their significance. Regardless, the Canadians were there and were expected to have sufficient time to train their forces for combat duties. Besides, the Japanese were not expected in the near future.

The British were wrong: the Japanese had been ready for quite a while. On 6 November 1941 the Japanese High Command issued orders for the capture of Hong Kong. Assigned to this task was the 38th Division of the 23rd Army. For its mission, the 38th Division was supplemented by the entire artillery complement of the 23rd Army. It was also reinforced with additional engineering, transport, and specialist battalions. On the day of the initial assault, the Japanese units, commanded by Lieutenant General Sano, were in position and eager for battle. To a man, an air of optimism prevailed.

The British High Command, however, was not completely oblivious to the Japanese troop movements across the frontier from Hong Kong. The Commonwealth commander, General Maltby, could not ignore persistent Chinese reports of hostile Japanese intentions. But were those troop movements merely diplomatic brinksmanship, or actual preparations for war? Maltby could not be sure; without direct orders to the contrary, he prepared for the worst.

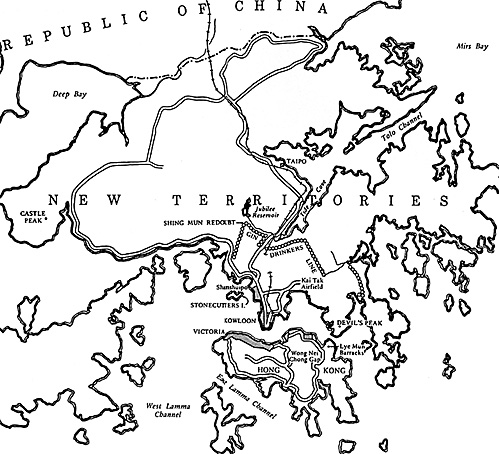

Originally, he had planned to defend the island and only skirmish on the mainland. However, with the arrival of the Canadian battalions, he adjusted his plans and deployed his forces into two separate brigades. The Island Brigade comprised the Middlesex, the Royal Rifles, and the Winnipeg Battalion. The Mainland Brigade included the Royal Scots, the Punjabis, and the Rajputs. The last three battalions were expected to hold partly- constructed and incomplete defensive works, known collectively as the "Gin Drinkers Line."

This line was notable in that its frontage was over ten miles long. Under original plans this line was to be held by two infantry divisions. Obviously, the line would be undermanned. Nevertheless, General Maltby felt confident. He fully expected this line to hold out for at least a week. Further, he felt confident that the island itself would be able to hold out for an additional nine weeks.

Map

The Fall of Hong Kong 1941

- Introduction

Japanese Attack: Dec. 8

The Assault on the Island

Final Assessment

Jumbo Map of Attack on Hong Kong (slow: 187K)

Back to Table of Contents: CounterAttack # 4

To CounterAttack List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by Pacific Rim Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com