The Japanese attack commenced at 8:00 am, on 8 December 1941, coinciding with the attack on Pearl Harbor. Preceding the actual land assault was an aerial strike. Within minutes the Japanese were able to achieve air superiority and maintain it for the campaign. This was never an issue, the British only had five obsolete aircraft, all of which were destroyed.

The Japanese attack commenced at 8:00 am, on 8 December 1941, coinciding with the attack on Pearl Harbor. Preceding the actual land assault was an aerial strike. Within minutes the Japanese were able to achieve air superiority and maintain it for the campaign. This was never an issue, the British only had five obsolete aircraft, all of which were destroyed.

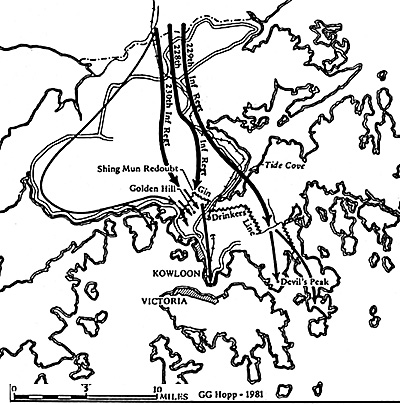

Map: The advance of the Japanese on the mainland.

Not to be outdone, the Japanese Navy surrounded Hong Kong and forged a steel wall with their ships through which the British could neither reinforce nor escape. Hong Kong, now completely beleaguered, was left to its own dwindling resources for defense. Suddenly, and with almost complete determination, the citizens of Hong Kong reported to their respective militias and prepared themselves for the struggle to come. The war was on.

Back on the mainland, the British quickly fell back to the Gin Drinkers Line, delaying the Japanese whenever and wherever possible. Complying with orders, demolition teams blew up or destroyed anything of potential use to the Japanese. Of highest priority were bridges and logistical centers. However, these efforts proved fruitless, as many of the blown bridges proved irrelevant. Many of the rivers were successfully crossed only hours after the British demolitions fired off.

The reason: Japanese engineering units often had pontoon bridges assembled prior to the actual bridge demolitions. The Japanese advanced rapidly and by 9 December were facing the Gin Drinkers Line.

The Japanese advance consisted of three attack groups: the 228th, 229th, and 230th regiments of the 38th Division. In the center, the 228th Regiment led by Colonel Doi expected a hard struggle. This was to be the first serious clash of forces. The British defenses centered on one position - the Shing Mun Redoubt. Its highest point dominated the adjacent valleys and the approaches to Kowloon. In short, it was the key to the mainland defense. And here, General Maltby placed his highest expectations. He proved to be too optimistic. The Redoubt, seriously undermanned, was about to fall.

Moving cautiously, Colonel Doi could not have known of his immense advantage. To hold the Redoubt, all that General Maltby could spare was a single Royal Scots platoon, a company headquarters, and an artillery observation post. To the east and west, the flanks were supposed to be covered by "roving" infantry platoons. These platoons were to locate and then converge on any Japanese breakthroughs. In reality, these forces could hardly move swiftly and were allocated far more terrain than they could handle. Coupled with that was the terrain itself. Broken and irregular, it was ideal cover for any advancing forces. On 9 December, Colonel Doi reconnoitered the area and set plans for his assault.

Determined to take the Redoubt, Colonel Doi committed two of his battalions and set the attack for 11:00 pm. Aided by their uniforms, and their specially requisitioned rubber-soled boots, they advanced undetected. Once at the heights, they rushed the entrenchments. The outnumbered Royal Scots were caught napping, but they quickly recovered. Stubborn hand-to-hand fighting spread to the pillboxes and the adjoining tunnels.

Redoubt Falls

The Japanese assault proved too strong; by 4:00 am the Redoubt was in Japanese hands. Not sure of the Japanese strength, General Maltby entertained thoughts of a counterattack. He knew that it would be a daunting task. More than any other unit, the Royal Scots suffered grievously from the effects of malaria. Of the battalion's authorized strength of 735, only 600 were available for duty.

When the nearest available troops were deemed to be too far away to be of practical use, Maltby recognized his plight and an order to retreat was issued. In accordance with this order, an artillery barrage commenced. It, unfortunately, resulted in tragedy, as the last remaining pillbox, cut-off and surrounded, received direct hits from friendly fire at approximately 7:00 am. After this, the Royal Scots retreated to new positions centered on Golden Hill, just south of the Redoubt. Here they regrouped and awaited the next onslaught. Elsewhere, the Rajput and Punjabi battalions fought off determined, but less serious, Japanese assaults.

At this point in time a great irony occurred. For not following orders in a strict manner, Colonel Doi was reprimanded. Regardless of his success, Colonel Doi had unexpectedly ventured into the territory of the 230th Regiment whose responsibility was the capture of the Shing Mun Redoubt. To the tradition conscious Imperial Army strict compliance of issued orders was always expected. Colonel Doi was ordered to pull back from the hill in order to retain what little honor he had left!

Defiantly, Doi refused to budge. The incident was only forgotten after every officer in the 228th, including Doi, renewed their pledges of allegiance to assigned orders.

Renewed Attacks

With their internal squabbles settled, the Japanese renewed their attacks. At 7:30 am of the l1th, the 230th Regiment thrust directly into the Royal Scots, whose defense was focused on "D" company, which held the crest of Golden Hill. Here, the battle quickly intensified; this continuous fighting was nothing short of determined bullheadedness by both sides.

The mauled Scots had something to prove: this time there would not be a repeat of their previous humiliation. Most importantly, other friendly battalions had started to refer to the Royal Scots as the "Regiment of the Foot." Their valor was in question.

In the Bushido warrior code, the Japanese 230th Regiment, led by Colonel Shoji, also had its honor at stake, having been outdone by the 228th's coup at the Redoubt. They were not about to let Colonel Doi's regiment steal their glory. The foundation was in place for a particularly vicious battle. Testimonial to the intensity of this battle were the losses suffered by both sides.

Within three hours of action, "C" company of the Royal Scots suffered twenty-five casualties of the thirty-five committed. "D" company fared even worse. As the focus of the Japanese assaults, it endured wave after wave of infantry assaults. Always outnumbered, it fought on gallantly. The Japanese also suffered heavily, but their exact number could not be determined. There were numerous moments of heroism on both sides.

At one point in the battle, Captain Pikerton, commanding the reserve company, disobeyed instructions and personally led a bayonet charge to retake the hill. Dodging bullets and throwing hand grenades, he so inspired his men that they stormed the hill and pushed off the more numerous Japanese. For his bravery and leadership, Captain Pikerton was later awarded the Military Cross. This officer would continue to exercise his leadership role throughout the campaign.

Despite his efforts, the Scots were forced back by the equally determined and more numerous Japanese. Simply put,. three well reinforced Japanese battalions pushed back the efforts of one weakened Commonwealth battalion. No amount of valor could undo this fact. The British had to revise their strategy. The possibility of fighting for Kowloon was ruled out because the civilian casualties would be too high. Fifth column forces exacerbated the worsening situation. Troops already had to contend with snipers and sabotaged equipment. Canadian troops received contradictory orders.

Eventually, they were ordered back to the island. Last, but not least, were concerns for the safety of the Indian battalions. With the fall of Golden Hill, there was real danger that they would be outflanked and possibly cut off.

At noon of the 11th, alarmed by the quick fall of the Gin Drinkers Line and recent reports of Japanese attempted landings to the southwest of Hong Kong Island, General Maltby made the momentous decision of withdrawing from the mainland. His one week stand lasted less than two days. Once underway, the withdrawal was hampered by panic-stricken crowds, abandoned vehicles, and accompanying hysteria.

At loading docks shots had to be fired to disperse the desperate crowds. Despite all this, most of the island troops were evacuated by 12 December. The Punjabis were given the role of rear guards. Some proved to be unlucky and were mowed down by the Japanese as they boarded the last evacuating ships. Only the Rajput battalion was left behind. They were to hold on to the strategically important Devil's Peak Peninsula.

Control of the peak was crucial for the island's defense. From it artillery could fire at will at almost every point on the island. In addition, it was also the narrowest point between the mainland and the island itself, at its southern tip. Almost immediately, the Japanese attacked. Fortunately, they did so under-strength and were continuously beaten off by the Rajput.

Unbelievably, General Maltby discounted the Rajput's efforts and ordered the battalion back to the island. Reluctantly, the Rajput obliged, but in their haste had to leave many of their mule trains behind. By 9:00 am 13 December, the withdrawal was complete. Retreating British officers reported that their demolitions were so extensive, that it would be weeks before the Japanese could use their artillery in any effective manner. Again they were wrong. The following day the first of many artillery shells fell upon Hong Kong. The calamity was just beginning.

Garrison Organized

On the island, the garrison forces organized themselves into two separate commands. The East Brigade under Brigadier Wallis consisted of the Royal Rifles, and the Rajputs. The West Brigade under Brigadier Lawson included the Winnipeg Grenadiers, the Punjabis, and the now battered Royal Scots. The Middlesex battalion was dispersed throughout the island pillboxes. Assisting the defense were various volunteer and artillery units.

On paper, the British forces were the equal of the Japanese, and morale was still high. In reality, Hong Kong's fate had already been determined. On 10 December news reached Hong Kong of the Japanese sinking of the British capital ships Prince of Wales (BB) and Repulse (BC). The ships once called "unsinkable" were to have been Churchill's answer to Japanese aggression. Combined with the disaster at Pearl Harbor, all hopes of Hong Kong being relieved vanished. Rumors circulated that the Chinese planned a major relief force. General Maltby did not deny the rumors, but he knew otherwise.

Rather than concentrate his forces at specific points, Maltby decided to disperse his troops throughout the island. Assigned to each brigade were reserve motorized platoons that were to strike at Japanese invasion areas when such areas were confirmed. The plan relied on quick reaction and rapid containment of threatened areas. The strategy had its flaws: few of his troops were motorized. The Canadians were not, and the Indian battalions were now without their mule trains.

Transport of supplies would prove difficult. The little transport available soon proved itself vulnerable. Influenced by Japanese propaganda, many of the Chinese drivers chose to abandon and/or sabotage their vehicles. Logistics command was force to spare valuable troops to truck driving details. Meanwhile, General Sano could depend on many advantages for the upcoming campaign.

With complete control of the air, he could call air strikes on any seen target. Daily air strikes proved the norm with land based artillery strikes supplementing with uncanny accuracy. Between 13 December and 18 December the Japanese systematically destroyed pillbox after pillbox along the entire coast. Fifth columnists helped by providing information and striking at vulnerable targets - British transport drivers being a common target. As the invader, General Sano could strike at any selected point and achieve local superiority of firepower. Lastly, the recent Japanese advances were largely ignored as proof of Japanese military competence. Many of the ill-prepared, insufficiently trained, Hong Kong garrison still boasted confidence and underestimated the Japanese soldier.

They did not realize that once assigned to a task the Japanese troops would pursue it with unparalleled devotion. For their part, the Japanese considered the British troops to be pampered, weak and unreliable. Given the circumstances, it is not surprising to have seen the Japanese offer surrender terms on 13 December and to have them promptly refused.

The Fall of Hong Kong 1941

- Introduction

Japanese Attack: Dec. 8

The Assault on the Island

Final Assessment

Jumbo Map of Attack on Hong Kong (slow: 187K)

Back to Table of Contents: CounterAttack # 4

To CounterAttack List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by Pacific Rim Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com