The battle of Dien Bien Phu has been called an "unfortunate accident." It was not an accident, but rather the culmination of over seven years of hard fighting between two willful adversaries. At stake was the control of Indochina, an area of considerable natural wealth and of strategic importance in Southeast Asia. After the Second World War, the French Union forces fought to retain Indochina for France, for the business interests that prospered from the local resources, and for the local leaders who supported French rule. That suzerainty, imposed in the mid-nineteenth century, had brought considerable improvements in transportation, agricultural and industrial methods, and health care to an area of ethnic and political diversity.

The battle of Dien Bien Phu has been called an "unfortunate accident." It was not an accident, but rather the culmination of over seven years of hard fighting between two willful adversaries. At stake was the control of Indochina, an area of considerable natural wealth and of strategic importance in Southeast Asia. After the Second World War, the French Union forces fought to retain Indochina for France, for the business interests that prospered from the local resources, and for the local leaders who supported French rule. That suzerainty, imposed in the mid-nineteenth century, had brought considerable improvements in transportation, agricultural and industrial methods, and health care to an area of ethnic and political diversity.

However, the Western concepts of civilization and progress introduced by the French colonial government were not always welcomed by the native peoples who already bad a long history of cultural achievement. Moreover, the indigenous population resented the political power wielded over their lives by the colonial administrators and their local satraps. The Vietnamese, in common with the other people of Indochina, had periodically challenged the French rule, but their attempts at armed violence had always failed. After World War II, however, when France was deeply involved in reconstruction and other interests, the prospects for self-determination seemed brighter to the nationalists of Viet Nam.

The vehicle for their aspirations was the "League for the Independence of Viet Nam" (VietMinh), organized by Ho Chi Minh, a student of Communism and of Asian politics since 1918. During World War II, the Viet-Minh devoted itself to organizing resistance to both the Japanese occupation forces and the French. When the war ended, Ho Chi Minh won recognition from the French of his "Democratic Republic of Viet Nam" in the north, but this was soon lost in 1946 when the French reasserted their authority over Viet Nam. Ho Chi Minh's government fled to the highlands of North VietNam, where he directed operations against the French as they tried to reoccupy their former colony.

At first, without adequate arms, the Viet-Minh were forced to use hit-and-run guerrilla tactics, that harassed the French Union forces. The pace of their activities was also governed by Vo Nguyen Giap, Ho Chi Minh's chief of military affairs. A student of the guerrilla warfare philosophy of Mao Tse-tung, Giap's strategy for victory envisioned a protracted conflict divided into three overlapping phases: (1) covert mobilization and small-scale guerrilla forays; (2) expansion into highly mobile guerrilla operations; and (3) finally, the classic conventional offensive operation.

As more weapons became available from Communist countries and French depots and as the Viet- Minh developed the ability to operate in units of regimental and divisional size, the opportunity for the third phase grew more likely. The French, aside from a few irregular units, had been fighting with roadbound conventional forces, supported by uncontested air and sea elements, and had begun to train a Vietnamese National Army along the same lines.

Where Giap overestimated his capabilities, as in his unsuccessful massive conventional attacks on the "Marshal de Lattre Line" in 1951, the French and their Vietnamese allies were able to defeat the Viet-Minh, but the constant drain of men and materials in guerrilla fighting weakened the military might and resolve of the French Union forces.

By late 1953, the armed forces of the French in Indochina approximated 190,000 regular and overseas troops, 150,000 men of the Vietnamese National Army, and 160,000 native auxiliary soldiers. The Viet-Minh could field 300,000 combatants, organized in the Viet Nam People's Army and guerrilla units, and had won the support from most of the peasant population. While all of Indochina had become a battleground in some form, both sides were clearly looking for a single conflict that would decide the war. They were to find it at a place called Dien Bien Phu.

"Seat of the Border County Prefecture"

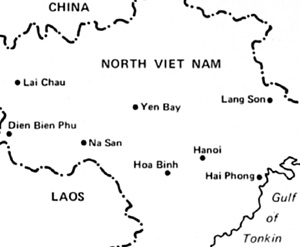

The site, a large valley in the northwestern comer of Viet Nam, supported a town known as the "Seat of the Border County Prefecture" (translated in Vietnamese as Dien Bien Phu) and an administrative center for the French colonial govemment. Dien Bien Phu was also a terminus for Provincial Road 41 and a marketplace for the local products of rice and opium. In addition, it

provided access to the populous highland region, an important source of political support and recruits from the T'ai natives. Moreover, Dien Bien Phu was a convenient route to Laos, only eight miles away and an area of increasing Communist activity. The occupation of the valley in late 1952 by units of the Viet Nam People's Army threatened northern Laos and denied the

French the accustomed benefits of the region.

The site, a large valley in the northwestern comer of Viet Nam, supported a town known as the "Seat of the Border County Prefecture" (translated in Vietnamese as Dien Bien Phu) and an administrative center for the French colonial govemment. Dien Bien Phu was also a terminus for Provincial Road 41 and a marketplace for the local products of rice and opium. In addition, it

provided access to the populous highland region, an important source of political support and recruits from the T'ai natives. Moreover, Dien Bien Phu was a convenient route to Laos, only eight miles away and an area of increasing Communist activity. The occupation of the valley in late 1952 by units of the Viet Nam People's Army threatened northern Laos and denied the

French the accustomed benefits of the region.

To reestablish control of Dien Bien Phu the French planners had only a limited military inventory at their command. Since 1946 billions of francs had been spent in the anti-nationalist campaign in Indochina, and while the United States had supplied great numbers of surplus weapons and airplanes, these were largely unfamiliar to the French military and their Vietnamese allies and required new logistical and technical skills that they had yet to master. Most critically, there was a need for manpower, a commodity not readily available from a metropolitan govemment with other pressing military commitments. By law, French draftees could not serve in Indochina. With the Viet-Minh growing bolder and able to field one artillery and six infantry divisions, with more units in training, the French Union forces needed a workable method to overcome their increasingly dangerous adversary.

By mid-1953 a method seemed available and proven battle-worthy in the concept of the air-land base or airhead. In theory, it consisted of a strongly defended hedgehog or system of hedgehog positions resupplied by transport aircraft and supported by combat aircraft. From such positions, friendly forces could spread insecurity in the enemy's rear and, hopefully, win back territory occupied by the Viet-Minh. If necessary, the airhead bases could become jungle fortresses to withstand enemy assaults, especially with the undisputed control of the air enjoyed by the French. The Viet-Minh, it was reasoned, would be unable to dislodge such airheads and become weaker as the French reextended their control.

The feasibility of the air-land base concept had apparently been shown at Na San, an airhead established in October, 1952. Over a penod of several months, a mixed force of French Union and native soldiers manning two complete circles of strongpoints and supported by artillery and continuous airlifts of supplies and men had withstood infiltration and "human wave" assaults by the 308th and 312th Divisions led by Giap. However, Na San had protected nothing of importance and had consumed enormous resources in men and matenal without seriously weakening the enemy. The new Commander-in-Chief of the French Union Forces in Indochina, Gen. Navarre, recognized the uselessness of the airhead and ordered the evacuation of its 9,000-man garrison, a move which totally surprised the Viet-Minh and strengthened the notion among French planners that airheads could be organized and terminated at will.

General Henri Navarre

Lieutenant General Henri Navarre had never held a field command in Indochina, a fact which helped in his selection by the French government. A veteran of the First and Second World Wars with experience in military intelligence, tanks, and anti-guerrilla fighting, Navarre was expected to bring a new direction to French operations in Indochina. However, aside from the customary changes in personnel and some tactical revisions, as at Na San, Gen. Navarre displayed little innovative genius in combating the Viet-Minh.

In truth, he had little freedom to do so. The French government denied him fresh troops or even adequate replacements, and materials were not increased. The war was unpopular in France, and Navarre was expected to win with what he had. And for Dien Bien Phu, Gen. Navarre had nothing to help him but the intentions of his predecessor and the policy of his government.

The reoccupation of Dien Bien Phu had been ordered by the previous French commander, Lieutenant General Salan. His top secret Directive 40 had outlined the need for the counterattack to regain control of the region and to secure the border with Laos. These priorities were assumed by Gen. Navarre when in July, 1953, he presented his plans for military operations in Indochina to the National Defense Committee in Paris. While different accounts have been given as to what was said and decided, Gen. Navarre returned to his headquarters in Saigon believing that he was to reestablish French control in the strategic northwest region of Viet Nam.

On November 13, 1953, nearly four months after his meeting in Paris, Gen. Navarre received a formal directive that the French Joint Chiefs of Staff and the National Defense Committee felt that "no obligation be put upon him to defend Laos," despite a treaty signed October 22 that implied that commitment. No mention was made of Dien Bien Phu. Gen. Navarre had already ordered the reoccupation of the valley and did not countermand the order.

More Dien Bien Phu

-

Dien Bien Phu: Introduction

Dien Bien Phu: French Arrival: 20 Nov. 1953

Dien Bien Phu: Vietnamese Attack: 13 Mar. 1954

Dien Bien Phu: French Counterattack: 10 Apr. 1954

Dien Bien Phu: Soldiers

Dien Bien Phu: Weaponry

Dien Bien Phu: French Order of Battle

Dien Bien Phu: Viet-Minh Order of Battle

Dien Bien Phu: Map: Last Days May 1-7 (slow: 126K)

Back to Conflict Number 6 Table of Contents

Back to Conflict List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1973 by Dana Lombardy

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com