On March 13, 1954, Gen. Giap consented to battle with the French on his terms. At mid-afternoon, the zeroed-in Communist artillery began to pound the airfield and defensive positions of the French. Their counterbattery fire failed to silence the Viet-Minh guns even though one-fourth of the reserve of 105-mm ammunition was used.

On March 13, 1954, Gen. Giap consented to battle with the French on his terms. At mid-afternoon, the zeroed-in Communist artillery began to pound the airfield and defensive positions of the French. Their counterbattery fire failed to silence the Viet-Minh guns even though one-fourth of the reserve of 105-mm ammunition was used.

At right, a Viet-Minh battalion on the march. Note the mounted officers and 75mm recoilless rifle teams carrying their guns and tripods. The thirty-one infantry battalions used against the French at Dien Bien Phu lost nearly 23,000 men killed or wounded during the siege.

Large Viet-Minh Bttn Photo (68K)

Two C-47 aircraft were destroyed along with two fighters, and at 1600 the control tower radioed that the airfield was closed. For the first time, Dien Bien Phu was sealed off from the outside world. Viet-Minh infiltrators were beaten off by the troops on Gabrielle, but Beatrice was subjected to continuous and accurate artillery bombardment that destroyed its command bunker.

Assault units of the 312th Division stormed the French barbed wire entanglements and, despite heavy casualties, forced the 3rd Battalion, 13th Foreign Legion Demi-Brigade, to abandon its positions. Over 550 Legionnaires were killed, and the first major position of the French fortress was lost. In spite of the requirement for a counterattack to retake Beatrice, this was forsaken in favor of reinforcing the remaining positions. The next day, the entire 5th BPVN was airdropped and installed on Eliane. Communist artillery continued to fire on the airfield, destroying the last six "Bearcats," the control tower, and the radio beacon. Dien Bien Phu thus lost its local air support.

Next Target

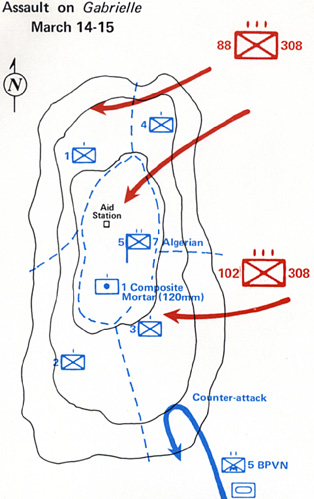

Gabrielle was expected to be the next target of a Viet-Minh assault and seemed well prepared for its role as a defensive bastion. It was the best built strongpoint at Dien Bien Phu, the only one with a second line of defense, and manned by the professionals of the 5th Battalion, 7th Algerian Rifles, and a Legionnaire heavy mortar company. At 1800, on March 14, enemy 120-mm mortars and 105-mm howitzers began to bombard the defenders, collapsing their bunkers and destroying their mortars and radio sets. However, the Bo-Doi (infantrymen) of the 308th Division were repulsed as they tried to infiltrate the Algerians' lines, in contrast to the costly human wave attacks on Beatrice. Early the next morning, the Communist bombardment and infiltration were renewed.

When machine guns from the northernmost bunker stalled the Viet-Minh advance, a People's Army gunner dragged a hand-built 75-mm wheeled bazooka to within 150 yards of the emplacement, scored three direct hits on it, and silenced the guns. With that and a lucky artillery burst on the command post that wiped out the battalion's leadership, the Communists seized the remaining positions. A counter-attack by the 5th BPVN and tanks failed, largely due to the reluctance of the Vietnamese to advance. The survivors of Gabrielle were escorted back to the main position under heavy enemy artillery fire.

The battle of Gabrielle was costly to both sides. The Viet-Minh sustained 2,000 dead and perhaps 3,000 wounded of one of their best divisions. However, they had won another French strongpoint. The Algerians lost about 500 men, and the Legionnaire mortar company had also

ceased to exist. One tank was severely damaged, and the newly arrived 5th BPVN had been shown to be worthless as a unit; many of the surviving Vietnamese paratroopers were stripped of their badges and sent to work as coolies. The artillery commander, Col. Piroth, stunned by the inability of his beloved guns to counter the accurate Viet-Minh fire, committed suicide, and Lt. Col. Keller, chief of staff for the fortress, suffered a nervous breakdown and had to be relieved. Moreover, an entire T'ai company on Anne-Marie disappeared into the nearby hills. Accurate Communist antiaircraft fire reduced parachuted supplies to 12.5 tons, not enough to make up for the huge expenditure of ammunition and other supplies in the recent battle.

The battle of Gabrielle was costly to both sides. The Viet-Minh sustained 2,000 dead and perhaps 3,000 wounded of one of their best divisions. However, they had won another French strongpoint. The Algerians lost about 500 men, and the Legionnaire mortar company had also

ceased to exist. One tank was severely damaged, and the newly arrived 5th BPVN had been shown to be worthless as a unit; many of the surviving Vietnamese paratroopers were stripped of their badges and sent to work as coolies. The artillery commander, Col. Piroth, stunned by the inability of his beloved guns to counter the accurate Viet-Minh fire, committed suicide, and Lt. Col. Keller, chief of staff for the fortress, suffered a nervous breakdown and had to be relieved. Moreover, an entire T'ai company on Anne-Marie disappeared into the nearby hills. Accurate Communist antiaircraft fire reduced parachuted supplies to 12.5 tons, not enough to make up for the huge expenditure of ammunition and other supplies in the recent battle.

The morale of the besieged fortress was given a lift by the return of Bigeard's 6th BPC. The entire battalion, plus 100 other paratroopers and three gun crews, were parachuted into the drop-zone on March 16. However, their assignment had not been made without some sacrifice by the headquarters in Hanoi. Other operations in the Red River Delta and Laos also required troops.

When Col. de Castries requested that another parachute battalion be placed on permanent alert for duty at Dien Bien Phu, Gen. Cogny replied that only one spare battalion was available for all of the Northern Command.

Supply

The supply situation at Dien Bien Phu was also critical, largely due to the inability of the supply services to replenish the stores of the encircled fortress. Transport aircraft and crews had always been at a premium in Indochina and many had already been lost at Dien Bien Phu. The few helicopters available could not carry large amounts of supplies and were used mainly for bringing in medical stores and removing casualties.

Two hundred tons of supplies were considered the minimum needed for the garrison to survive, but on many days the stores received amounted to fifty tons or less. As accurate Viet-Minh artillery fire reduced the usefulness of the airfield, despite heroic efforts by the Moroccans of the 31st Engineer Battalion, the air-dropping of supplies was relied upon more and more.

By the end of March, no aircraft or helicopters could land or take off from Dien Bien Phu. But the parachuted supplies were not adequate to maintain the garrison since their loads were necessarily small and many drops were destroyed on impact or drifted into Viet-Minh territory. Heavy rain canceled air missions on many days. Also the murderous Communist flak made the French pilots and the contract pilots of the American-operated Civil Air Transport Company reluctant to fly in a valley whose concentration of antiaircraft artillery was considered greater than anything encountered during World War II and Korea. Air sorties had already proven unable to reduce this danger and only added to the losses in aircraft and crews. At Dien Bien Phu, the Communist gunners were to destroy sixty-two aircraft and to damage 167 others before the battle was over.

To give his fortress a chance to live, Col. de Castnes decided to dispatch some of his own forces to destroy the enemy's flak batteries. Maj. Bigeard was given the job and the freedom to use what he needed to eliminate the Viet-Minh antiaircraft positions west of Claudine and guarded by the tough 36th Regiment. For his assault forces, Bigeard chose five battalions, including his own 6th BPC and the 1st BEP, and two tank platoons, all backed up by artillery of the fortress and fighter and bomber aircraft. Following a short and heavy rolling barrage, the paratroopers and tanks smashed into the Communist positions. The stunned enemy retreated, leaving 350 dead, five 20-mm antiaircraft cannon, and several machine guns and automatic weapons.

However, despite their success, the French assault forces lost a score of men and lacked the troops to occupy the gun positions so close to othe Viet-Minh units. After the paratroopers returned to their fortress, the Communists had new antiaircraft batteries installed in the former positions to harass the air supply runs by the French.

Attack

Communist attention to the French positions of Eliane and Dominique had become more evident. Nightly, the French outposts could hear the sound of approaching trenchworks, a hallmark a preparation by Viet-Minh assault forces.

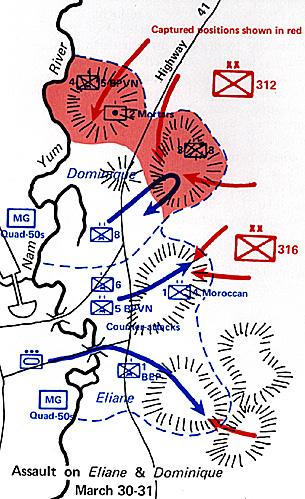

Suddenly on the evening of March 30, a terrific Communist artillery barrage engulfed the two French strongpoints and the headquarters area. The Algerians on Dominique and its outposts fled befor the assault waves of the Viet-Minh's 312th Division but the African gunners of the 4th Colonial Artillery Regiment depressed their

howitzers to minimun elevation and fired point-blank into the massed Bo-Doi. This fire was joined by the quad-fifties, and the Communist infantrymen, too close to the enemy for support from their own artillery, retreated straight into a minefield recently laid by the French. On Eliane, the Moroccans and Foreign Legionnaires were overrun by the entire 316th Division, but scattered positions continued to resist until an immediate counterattack by paratroopers of the 1st BEP and two tanks could reestablish a tenuous hold over much of the strongpoint.

Suddenly on the evening of March 30, a terrific Communist artillery barrage engulfed the two French strongpoints and the headquarters area. The Algerians on Dominique and its outposts fled befor the assault waves of the Viet-Minh's 312th Division but the African gunners of the 4th Colonial Artillery Regiment depressed their

howitzers to minimun elevation and fired point-blank into the massed Bo-Doi. This fire was joined by the quad-fifties, and the Communist infantrymen, too close to the enemy for support from their own artillery, retreated straight into a minefield recently laid by the French. On Eliane, the Moroccans and Foreign Legionnaires were overrun by the entire 316th Division, but scattered positions continued to resist until an immediate counterattack by paratroopers of the 1st BEP and two tanks could reestablish a tenuous hold over much of the strongpoint.

The Viet-Minh had also launched probing attacks on Huguette, but the main concern of the French was to regain complete control on Dominique and Eliane. Despite the fact that Legionnaires and tanks from Isabelle were unable to break through to aid the counterattack, the entire GAP2 with "Bisons" from the central position and the remaining Vietnamese paratroopers of the 5th BPVN succeeded in retaking all of the lost positions. But they needed reinforcements to retain their victory and the headquarters at Dien Bien Phu pleaded with Hanoi to send a parachute battalion.

Cogay's staff vacillated, then denied the request on the grounds that airborne reinforcements would be destroyed by the heavy Viet-Minh fire while parachuting. Disheartened, de Castries' soldiers abandoned the exposed positions of Dominique. Most of Eliane was not to be surrendered, however, and a determined stand by Bigeard's troops and three "Bisons" retained the position, though one tank was soon destroyed and the other two damaged by enemy 57-mm recoiless rifles.

Frustrated to the east, the Viet-Minh began to challenge the French for the area around Huguette, northwest of the airffeld. Again and again, infantrymen of the 312th Division assaulted the mixed force of Foreign Legionnaires, Vietnamese, and T'ai riflemen, but each time they were repulsed, often with the aid of soldiers and tanks from the central position. However, this defense created more casualties. The wounded soon overwhelmed the tiny medical facilities.

When they became too many for the few beds and stretchers available, some 1,000 wounded were assigned to the mud and filth of hastily excavated tunnels and bunkers, often without sufficient light, water and food. There was none available. Faced with such conditions, it is not surprising that those soldiers able to walk returned to their units where fighters were always needed.

Rats of Nam Yum

The shortages in manpower were aggravated as the T'ai auxiliaries continued to abandon their positions, sometimes defecting to the Viet-Minh, but often joining the estimated 3,000 Algerian, Moroccan, Vietnamese, and European deserters hiding in a separate camp at the center of Dien Bien Phu. Known as the "Rats of Nam Yum," they stole food and weapons from the fighting forces. To dislodge these "internal deserters" would have meant an extra battle for the already weakened defenders. Along with the families of the tribesmen seeking sanctuary at Dien Bien Phu, plus two mobile bordellos contracted for the pleasure of the non-European troops, the deserters constituted a severe strain upon the resources and security of the embattled fortress.

Faced with a shortage of workers, the French employed willing Viet-Minh captives and defectors to build defenses and to haul supplies and ammunition, activities which are not outlined by the Geneva Conventions. Many times these prisoners-of-war were sent to collect misdropped supplies. Although without guards and under fire by their former comrades in the surrounding hills, the prisoners almost always returned.

Indeed, of the 3,000 Communist captives held by the French, only a few dozen tried to escape, although many were listed as "missing" and then recruited under other names as new soldiers for the French Union forces.

In Hanoi, Gen. Cogny relented on the withholding of further reinforcements and ordered the II/1 RCP to be air-dropped on Dien Bien Phu. However, the initial reinforcements were added only a few men at a time, partially due to the heavy flak that prevented air runs, but also because of the bureaucratic requirement that a properly identified drop-zone be prepared for a mass jump.

The command at Dien Bien Phu finally convinced Hanoi that a regulation drop-zone could never be established under the circumstances, and most of the II/1 RCP was finally available to the garrison by April 5. The need for specialists, such as gun crews and radio men, also was critical, and when no more qualified parachutists could be found who had the needed skills, non-parachutist volunteers were allowed to jump into Dien Bien Phu. A total of 4,291 reinforcements were air-dropped into the valley fortress of whom 681 were nonqualified jumpers. The latter were awarded their airborne badges when they reported to Col. de Castries.

To replace their losses at Dien Bien Phu, the Viet-Minh had to draw on their forces from all over Indochina. Dien Bien Phu absorbed five percent of the French battle force in Indochina, but the battle eventually required fifty percent of the Communist combatant troops and an overwhelming share of the military supplies provided by Red China. Had the French skillfully withdrawn their garrison in December, 1953, they would have left most of the Viet-Minh combat strength stuck in an obscure corner of Viet Nam. Instead, the French were trapped at Dien Bien Phu. Gen. Giap, whom the French generals had once called "a noncommissioned officer learning to lead regiments," confidently ordered up additional replacements, including seasoned veterans and teenage boys, plus local tribesmen pressed into service as coolies.

More Dien Bien Phu

-

Dien Bien Phu: Introduction

Dien Bien Phu: French Arrival: 20 Nov. 1953

Dien Bien Phu: Vietnamese Attack: 13 Mar. 1954

Dien Bien Phu: French Counterattack: 10 Apr. 1954

Dien Bien Phu: Soldiers

Dien Bien Phu: Weaponry

Dien Bien Phu: French Order of Battle

Dien Bien Phu: Viet-Minh Order of Battle

Dien Bien Phu: Map: Last Days May 1-7 (slow: 126K)

Back to Conflict Number 6 Table of Contents

Back to Conflict List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1973 by Dana Lombardy

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com