The continued enemy presence on one of the highpoints of Eliane made necessary an assault by the French to seize and hold this position. Maj. Bigeard was again called on to plan the operation. He assigned what remained of his 6th BPC, Brechignac's II/1 RCP, and the Legionnaires of the 1st BEP to dig approach trenches, Viet-Minh style, toward the enemy bunkers. Then, on April 10, with the remaining twenty 105-mm howitzers of the French shelling the elevation and "Helldivers" of the Navy bombing nearby Viet-Minh positions, Bigeard's troops advanced rapidly in small groups, like commandos, using automatic weapons and flamethrowers to rout a crack regiment of the 316th Division. As so often happened at Dien Bien Phu, the local Communist commandes failed to adjust rapidly to a new situation or to show initiative.

Finally, under orders from Giap's headquarters, the Viet-Minh did counterattack in strength, but the French troops, reinforced by Vietnamese paratroops and elements of the newly arrived 2nd BEP, held the hill. They were to stay there until the end.

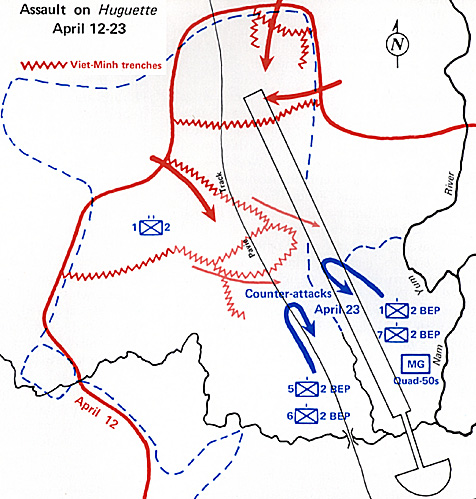

Growing cautious because of the heavy casualties sustained by his soldiers, Gen. Giap ordered more approach trenches to be dug around the French positions. Many of these were excavated underground in tactics reminiscent of World War I. The French could not countermine because of their lack of men and materials. From the new surface approaches, the Viet-Minh could snipe at the French troops and send forward "death volunteers" loaded with explosives to blow up French bunkers. Strongpoint Isabelle had long since been cut off from the main garrison by the trenches and artillery of the 304th Division. The outer positions at Huguette were isolated by Viet-Minh trenchworks, reinforced with mines and automatic weapons pits.

The French Union soldiers there could be resupplied only with heavy losses. Lacking the troops to eliminate the enemy trenches, the French tried to nullify their usefulness by planting booby traps and raiding enemy outposts, but the Viet-Minh sent more soldiers to replace the casualties and to dig new positions. On April 23, major bunkers at Huguette were lost to Communist assault troops who attacked the French from trenches only a few yards away.

De Castries, now promoted to Brigadier General, ordered a counterattack to regain control of the main position at Huguette or else even the driblets of parachuted supplies would be lost if the Viet-Minh controlled the airfield/drop-zone. However, Col. Langlais, nominally de Castries' subordinate, but according to his own and other accounts the de facto commander of Dien Bien Phu, opposed the operation. Langlais enjoyed the support of most of the other unit commanders, particularly the "Paratroop Mafia," and had directed much of the defense of the fortress, leaving de Castries to maintain contact with Hanoi.

The proposed attack, he argued, would be a serious drain on their fighting strength with no certainty of success. Bigeard, now a lieutenant colonel, also opposed the operation, but he was persuaded by Gen. de Castries to draw up plans for the assault. Supported by howitzer fire and dive bombers, the 2nd BEP surprised the newly installed perimeter guards of the Viet-Minh on Huguette.

However, the French attack bogged down under the fierce fire of the Communist machine guns and artillery, the tanks did not advance as expected, and the assault commander failed to coordinate his units. Bigeard intervened in time to withdraw most of the troops, but not before 150 men had become casualties. The last reserve of the French garrison was wiped out, and the Viet-Minh still controlled the drop-zone.

The obviously deteriorating situation at Dien Bien Phu did not occur without close attention by higher headquarters and national governments, both French and foreign. Various schemes were proposed to relieve the pressure on the encircled fortress and some of the ideas were actually attempted.

French "Operations"

In late March, the French Air Force executed Operation "Neptune," using C-119 "Flying Boxcars" to drop six-ton loads of napalm on the enemy trenches around Dien Bien Phu. While copious amounts of napalm were used, the waterlogged rain forest resisted being turned into a raging infemo, and the Viet-Minh positions were not significantly reduced. If the enemy could not be incinerated, perhaps he could be drowned, or at least 80 thought Gen. Navarre.

In early April, he ordered an officer to study the feasibility of creating artificial rain to inundate the roads used by the enemy convoys and thus stop the Viet-Minh supplies. The officer reported that, while precipitation could be induced by "seeding', the monsoon clouds with silver iodide, the inability to control the clouds and the winds made the results uncertain. The plan was reluctantly shelved. In the meantime, the Viet-Minh supplies continued to move despite the natural monsoon, while the French soldiers at Dien Bien Phu cursed the rain that flooded their positions.

Another plan that received close study called for intervention by American bombers, using conventional bombs and nuclear devices. Titled "Vulture," this operation was to be carried out by U.S. B-29 heavy bombers from the Philippines and aircraft from carriers of the Seventh Fleet. However, when it became clear that no allied nation outside of France would support this action, the American leadership withdrew its participation although it continued to send war materials for use by the French. The United States also sent delegates to Geneva where a multi-nation conference was to consider, among other matters, a cease-fire in Indochina.

French planners tried to aid Dien Bien Phu by other means. Operation. "Condor," an ambitious effort involving ground columns and parachute strikes against Viet-Minh rear areas, was reduced in scope as the situation at Dien Bien Phu became more desperate and the required air transport could not be made available. Instead, small independent forces, largely from Laos, drove on the beseiged fortress. They were indifferently supported by air and ran into numerous Viet-Minh roadblocks and ambushes set by the 148th Independent Regiment. By early May, none of the relief columns were near Dien Bien Phu nor could they help in another French operation, dubbed "Albatross." This called for a breakout by the forces at Dien Bien Phu to link up with friendly forces outside the valley. The breakout forces would be supported by all available artillery and combat aircraft and would travel with only individual weapons and rations. Heavy equipment and the wounded would be left behind. Like the other French plans in operation, this one proved to be unsuccessful.

By late April, the Viet Nam People's Army was also beset with problems. Although gaps in the front-line units were being filled with new recruits, critical supplies had become momentarily unavailable due to the rains and the French air strikes. Ammunition for the 120-mm heavy mortars was nonexistent, and medical supplies were not sufficient for the growing numbers of wounded. Also, the heavy casualties of the continued assaults had caused a severe drop in the morale of the Communist formations. Orders were not being obeyed in some units and various commanders had been replaced.

Ten years later a North Vietnamese study was to admit that Gen. Giap had to "launch a campaign for moral mobilization and 'rectification' of Rightist tendencies" among his troops in late April. Ignoring the aid from Communist China and the Chinese general in his own headquarters, Giap appealed to the nationalist pride of his army and urged that they not abandon the sacrifices already made. Ho Chi Minh also called on the soldiers to continue the battle. All that was required, both men argued, was one more effort to finish off the determined French resistance.

May Day Attack

On May 1, Labor Day and a Communist holiday, the Viet-Minh artillery opened fire on all the French positions at Dien Bien Phu. The combatants at the main garrison, now numbering less than 2,900 effectives, had contracted their defenses to an area around the southern end of the airfield. Only one 155-mm howitzer was left, along with a single tank in running order. On Isabelle, a thousand riflemen were crowded into an area less than one-fourth of a square mile. Air transports had braved fierce flak to deliver some needed supplies, but very few volunteers had parachuted alive into friendly areas and ammunition was critically short.

Communist Assaults

The Communist assaults began on what remained of Eliane, Dominique, and Huguette. Companies of the II/1 RCP were overrun on Elaine, but the Foreign Legionnaires on the hill stood fast. The position was partially retained and reinforced by 107 men of the 1st BPC who were air-dropped during the battle.

The Algerians and T'ai tribesmen in the outer trenches of Dominique were eliminated by the assault waves of the 312th Division. The 308th Division engulfed several positions at Huguette. The radio station at the central fortress reported: "No more reserves left, extreme fatigue and weariness of all concerned."

Elements of the 1st Colonial Parachute Battalion were added to the fortress on May 3, despite heavy rain that prevented many of the air transports from delivering their desperately needed supplies. Their arrival, however, could not make up for the previous days' casualties. The wretched state of the fighting strength of Dien Bien Phu was exemplified the next day when a force of 3,000 Bo-Doi overwhelmed, with heavy casualties, one of the last strongpoints on Huguette.

The commander at Huguette scraped together a force of 100 paratroopers and Moroccans, plus one tank, and immediately counterattacked, but was rebuffed by the 2,000 Viet-Minh occupying the former French outpost. No artillery or aircraft was available to aid the vain assault.

May 6 began with the largest supply drop in almost three weeks. Nearly 100 paratroopers of the 1st BPC, including many Vietnamese, were also safely inserted at Dien Bien Phu. This success was entirely due to the massive flak-suppressive mission staged by sixty fighters and fifty-two bombers that silenced the Communist batteries. Col. Langlais, apparently exercising his role that morning as the real commander at Dien Bien Phu, told the stronghold captains that there was still a chance if the remainder of the 1st BPC could be air-dropped and if the relief columns of Operation "Condor" arrived soon. The Geneva Conference might also negotiate a cease-fire. All that they needed, the Colonel said, was another twelve hours of relative quiet.

They were not to have it. At noon on May 6 the main garrison and Isabelle shook to thousands of rounds of artillery fired from the Viet-Minh batteries. Soviet-built "Katyusha" rockets joined the barrage, crumbling the already weakened field fortifications and arriving with such an ear-bursting screech that many of the non-European defenders fled their posts in terror. As usually happened in the heavy barrages, depots began to explode and supplies were destroyed. Then, on the eastern slopes of Eliane, 1,000 infantrymen of the crack "Capital Regiment" of the 308th "Iron Division" charged toward the remaining French positions.

The last French howitzers and mortars responded with a barrage that shattered the Viet-Minh assault but also drew another round of bombardment from the Communist guns. The "Capital Regiment" again attacked, only to be beaten off by hastily gathered reinforcements. At this instant, a huge mine exploded below the French bunkers, the result of industrious digging by the Viet-Minh miners. Dozens of soldiers were killed, but somehow the French held. The pleas from Eliane for more men and ammunition could not be answered, however, by the main garrison.

On Isabelle eight of the remaining nine howitzers were destroyed, and assured of no reprisal from that quarter, the rest of the 308th Division advanced on the main bunkers of Claudine, only to be thrown back by soldiers of the 2nd Foreign Legion Infantry Regiment. However, by early May 7, the Viet-Minh had advanced so close here and in other sectors, that the French Air Force could not accurately drop bombs or supplies.

Also, the remainder of the 1st BPC could not be parachuted in with any degree of certainty that they would land on French positions. Completely cut off from the outside and faced with imminent attack by the enemy, the commanders at Dien Bien Phu discussed the possibility of implementing Operation "Albatross," the breakout plan. Since the heavy Viet-Minh attacks had come from the east, it was likely that the western flank was relatively weaker.

Surrender

However, fresh aerial photographs, dropped as usual by a courier plane, showed that new trenches were dug to the west. To expect already exhausted troops to assault these positions, much less overcome them and escape, was too much. Even Bigeard refused to consider the attempt, and so, except for a few individuals from Isabelle, no one was to leave Dien Bien Phu except as a prisoner.

Gen. de Castries reasserted his authority in the last hours of his command as he listened to the bleak reports of his subordinates. The eastern defenses had fallen and no immediate reinforcements could be expected. Further resistance was impossible. The question now was whether or not to stop the fighting before dark. Mindful of the broken communications with most of his units and the pitiful state of his wounded, de Castries decided to cease hostilities before the light was gone.

He ordered all firing to stop at 1730. All equipment and supplies were to be destroyed. Gen. Giap was to be informed of the order. Gen. de Castries then radioed Hanoi as to his decision. Gen. Cogny urged him not to surrender under a white flag in respect to the gallant effort by the garrison. Gen. de Castries said he would not and then bid au revoir to Coguy. A few minutes later, he destroyed his transmitter. Around the headquarters the professional soldiers carried out the orders of their commander. The remaining supplies, weapons, and ammunition were burned or wrecked, though some foodstuffs and medicine were hoarded for the days ahead.

By the next morning, the 308th "Iron Division" was in occupation of de Castries' command bunker. The French air-land base at Dien Bien Phu had ceased to exist. Less than 100 men of the French Union forces, most of them non-Europeans from Isabelle, managed to elude the surrounding enemy and escape in the jungle.

The Viet-Minh were busy guarding and sorting the rest for the intelligence specialists to interrogate. From the previous months of fighting, they had a total of 10,000 captives to process, many of them wounded and all of them physically spent. In general, the initial treatment of the defeated seems to have been as good as could be expected, although the paratroopers and pilots were singled out for special "screening" and most of the medical supplies parachuted from French transports were not used on French wounded. However, there was still a war going on, a fact which delayed the return of many French casualties to their own hospitals.

Some of the 7,000 French prisoners captured at Dien Bien Phu being marched to the prison camps Nearly 5,000 died before repatriation.

Some of the 7,000 French prisoners captured at Dien Bien Phu being marched to the prison camps Nearly 5,000 died before repatriation.

Likewise, those prisoners able to walk were marched interspersed with Viet-Minh infantry and artillery columns to prevent their being bombed and strafed by the French Air Force. They were sent to prisoner-of-war camps 300 miles to the east whose facilities could best be described as primitive. Only one-third of the nearly 7,000 French military prisoners were alive to be repatriated in July, 1954. The rest had joined the 3,000 French Union soldiers and airmen who had died at Dien Bien Phu.

For the Viet Nam People's Army, their victory had cost 7,900 dead and 15,000 wounded. This does not include the thousands of casualties suffered on the supply roads or in the replacement camps that were subjected to French air attacks. As with the French, many Viet-Minh died of disease. The war, however, did not end for the Viet-Minh at Dien Bien Phu. Indeed, the French and their Vietnamese allies soon made good their losses in men and material, and Gen. Giap had to delay his attack on the Red River Delta. Militarily, Dien Bien Phu proved that an encircled force, no matter how valiant, will succumb if its support system fails.

The divided command of the French Union forces, and the varying degrees of allegiance of those fighting the war for France only compounded the basic problem. Politically, the battle showed that in revolutionary wars determination can decide issues and promote causes. After Dien Bien Phu, the French never fought a major battle in Indochina. As before Dien Bien Phu, the Viet-Minh never stopped fighting.

More Dien Bien Phu

-

Dien Bien Phu: Introduction

Dien Bien Phu: French Arrival: 20 Nov. 1953

Dien Bien Phu: Vietnamese Attack: 13 Mar. 1954

Dien Bien Phu: French Counterattack: 10 Apr. 1954

Dien Bien Phu: Soldiers

Dien Bien Phu: Weaponry

Dien Bien Phu: French Order of Battle

Dien Bien Phu: Viet-Minh Order of Battle

Dien Bien Phu: Map: Last Days May 1-7 (slow: 126K)

Back to Conflict Number 6 Table of Contents

Back to Conflict List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1973 by Dana Lombardy

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com